2. 北京医院检验科, 北京 100730;

3. 西安交通大学医学院第一附属医院检验科, 陕西 西安 710061;

4. 北京大学第一医院检验科, 北京 100034

2. Department of Laboratory Medicine, Beijing Hospital, Beijing 100730, China;

3. Department of Laboratory Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an 710061, China;

4. Department of Laboratory Medicine, Peking University First Hospital, Beijing 100034, China

毗邻颗粒链菌(Granulicatella adiacens)为兼性厌氧革兰阳性球菌,Frenkel等[1]在1961年首次于亚急性细菌性心内膜炎和中耳炎患者的血培养中分离获得,是颗粒链菌属中最常见的一种,呈卵圆形、球杆状或杆状,单个或短链排列,其形态与营养状态相关,生长缓慢,属于营养变异链球菌(nutritionally variant Streptococcus, NVS),需要补充巯基化合物满足其生长需求或与其他细菌共生长[2],如嗜血杆菌、葡萄球菌、链球菌等,这些细菌提供盐酸吡哆醛,帮助毗邻颗粒链菌生长,形成卫星菌落现象[3-5]。毗邻颗粒链菌可导致菌血症、败血症和心内膜炎等,但因培养困难,抗菌药物使用等原因,临床分离菌株数少。本研究收集全国细菌耐药监测网(China Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System, CARSS)成员单位的数据,分析2014—2021年血标本分离毗邻颗粒链菌的耐药性变迁,为临床治疗提供依据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 细菌来源2014—2021年CARSS成员单位上报的所有血标本分离的毗邻颗粒链菌数据,经系统自动审核和人工审核后,以保留每例患者毗邻颗粒链菌第一株的原则剔除重复菌株后纳入分析。2014—2021年全国上报数据基本合格纳入分析的成员单位数量分别为1 110、1 143、1 273、1 307、1 353、1 375、1 371、1 373所。

1.2 细菌鉴定与药敏试验细菌鉴定采用手工方法或自动化检测仪鉴定到菌种,药敏试验方法包括纸片扩散法、自动化仪器法和E-test法,药敏试验结果参考美国临床实验室标准化协会American Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)[6]标准判断。

1.3 质量控制按照CLSI要求进行质量控制。质控菌株包括金黄色葡萄球菌ATCC 29213, 肺炎链球菌ATCC 49619。

1.4 数据分析应用WHONET 5.6软件,分析血标本分离毗邻颗粒链菌数量变化及对不同抗菌药物耐药性变迁。

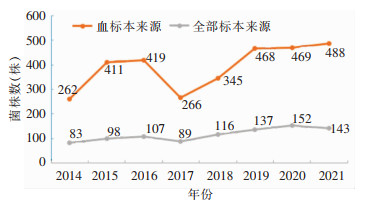

2 结果 2.1 毗邻颗粒链菌年度检出情况2014—2021年所有标本分离毗邻颗粒链菌分别为262、411、419、266、345、468、469、488株,其中血标本分离的菌数分别为83、98、107、89、116、137、152、143株,2017年后呈逐渐增多趋势。2014—2021年血标本分离的毗邻颗粒链菌菌株数变化趋势见图 1。

|

| 图 1 2014—2021年CARSS全部标本及血标本分离毗邻颗粒链菌菌株数变化趋势 Figure 1 Changing trend in the number of G. adiacens strains isolated from all specimens and blood specimens, 2014-2021 |

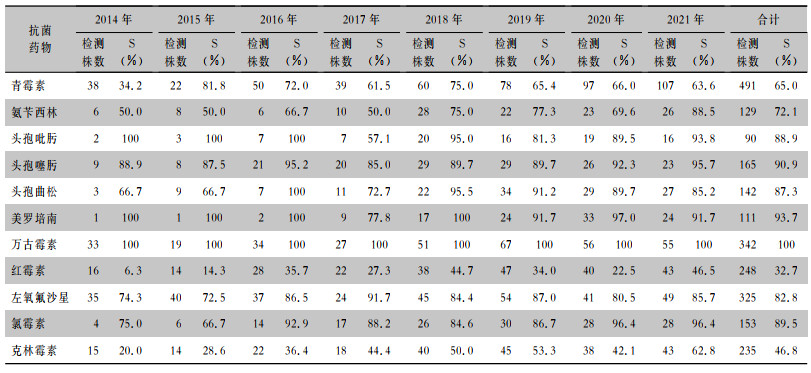

血标本分离毗邻颗粒链菌对万古霉素敏感率为100%,对美罗培南的敏感率为93.7%,对头孢曲松、头孢噻肟、头孢吡肟的敏感率为90%左右,对左氧氟沙星的敏感率为82.8%,对青霉素的敏感率为65.0%,对红霉素和克林霉素的敏感率较低,分别为32.7%、46.8%。2014—2021年毗邻颗粒链菌对青霉素、氨苄西林、头孢噻肟、头孢曲松、红霉素、左氧氟沙星、氯霉素、克林霉素敏感率均有不同程度上升,对头孢吡肟、美罗培南敏感率有所下降。见表 1。

| 表 1 2014—2021年CARSS血标本分离毗邻颗粒链菌对抗菌药物的敏感结果 Table 1 Antimicrobial susceptibility testing results of G. adiacens isolated from blood specimens, CARSS, 2014-2021 |

|

毗邻颗粒链菌属于NVS,为无芽胞、兼性厌氧的革兰阳性球菌,存在于口腔、胃肠道、泌尿生殖系统正常菌群中[2]。但由于其营养要求高,不易生长,或生长缓慢,采用标准培养基敏感性差[7-8],临床上较少分离到该菌。据估计,颗粒链球菌属所致的感染性心内膜炎占链球菌感染的3%~5%[4-5, 9]。但由于这类细菌对营养的特殊要求,近1/3的颗粒链球菌感染心内膜炎病例血培养呈阴性,还有部分血培养假阴性(即血培养阳性,但转种后不生长)和鉴定错误的病例,因此,NVS心内膜炎病例的真实数量可能被严重低估[4-5, 9-10]。

随着研究进一步深入,颗粒链球菌属所导致的疾病日益引起人们的重视。本研究发现,2014—2021年全国每年血标本临床分离毗邻颗粒链菌为83~152株,且在2017年后呈逐渐增多趋势,说明在我国越来越多的人认识到毗邻颗粒链菌会导致各系统的严重感染。因该类菌应用标准培养基和检测方法检出率较低,很容易被忽视,微生物工作人员必须提高警惕,当革兰染色显示有微生物细胞但培养结果呈阴性时,应怀疑NVS,尽早采用适当的补充营养培养基和可靠的检测系统进行分离。

由于毗邻颗粒链菌定植于口腔,可存在于牙菌斑中,引起牙髓感染和牙周脓肿等疾病[11],患者可在牙科操作后出现菌血症[12]或感染性心内膜炎[13-14]。Christensen等[3]从97例患者中分离获得的乏营养球菌和颗粒链球菌属主要来自血标本,但有3例来自眼部溃疡标本,58%患者诊断患有感染性心内膜炎,26%患者诊断患有菌血症或败血症,提示该类菌与感染关系密切。因此,虽然颗粒链球菌属感染并不常见,但其与菌血症和感染性心内膜炎明显相关。目前,颗粒链球菌引起感染性心内膜炎的机制尚不完全清楚。普遍认为心脏的病理情况是导致感染的主要因素之一[7, 14],而口腔健康不佳、过去6个月内的牙科操作可能促进感染性心内膜炎的发生[15]。毗邻颗粒链菌与心脏瓣膜的结合能力强,最常累及主动脉瓣和二尖瓣,且治疗较困难,常出现治疗失败的案例,约1/4的患者最终需要人工瓣膜置换治疗[16]。研究发现,颗粒链球菌感染导致的感染性心内膜炎患者的病情恶化经常比肠球菌或草绿色链球菌更为严重,治疗更为困难[4, 17],尽管给予了合适的抗菌药物治疗,但其复发率仍达41%[18]。Senn等[14]指出,在老年患者中,颗粒链球菌属的致病性和病死率更高,应引起临床工作者的高度重视。及早分离这些细菌以及进行联合瓣膜置换手术可以减少感染性心内膜炎的病死率。

除去上述菌血症、感染性心内膜炎外,颗粒链球菌属还可引起多种感染,包括腹膜透析相关性腹膜炎[19]、自发性腹膜炎[20]、感染性颅内动脉瘤[13]、化脓性关节炎[21-22]、骨髓炎[23-24]、乳房假体移植术后感染[25]、全膝关节成型术后感染[26]、脑脓肿[27]、脓胸[28]、中枢神经系统感染[29-30]、脑膜炎[31]、角膜炎[32]、眼内炎[33]、上颌窦炎[34]、尿道感染[35]、股动脉血栓[15]。

颗粒链球菌属细菌所致感染治疗较困难,临床微生物实验室对颗粒链球菌属没有常规进行抗菌药物的敏感性测试,根据体外数据,约40%的分离株对青霉素敏感,其中超过50%的分离株处于中间范围,万古霉素是唯一一种未发现对其产生耐药的抗菌药物[36]。颗粒链菌感染经验性使用青霉素和庆大霉素抗感染治疗往往耐药,常延误抗感染治疗或导致抗感染疗程不足。与在革兰阳性球菌的其他属中观察到的情况类似,颗粒链球菌属对青霉素耐药,导致使用青霉素治疗颗粒链球菌属引起的严重感染疗效不确定。毗邻颗粒链球菌心内膜炎的治疗失败率接近40%,复发率为17%[36-38]。在一项调查中,NVS感染的病死率为9.0%[39]。

英国抗菌化学学会建议,使用大剂量青霉素G和庆大霉素治疗颗粒链球菌属心内膜炎的疗程为4~6周[40]。欧洲心脏病学会建议使用青霉素G、头孢曲松或万古霉素治疗6周,前2周联合氨基糖苷类[41]。因此,通常需要使用青霉素或头孢曲松和氨基糖苷类进行4~6周的联合抗感染治疗[42-44]。美国心脏协会还建议使用氨苄西林、青霉素或头孢曲松(如果敏感) 加庆大霉素的联合治疗,仅当患者不能耐受青霉素G或氨苄西林时,才选用万古霉素。选用万古霉素时,可不联合庆大霉素进行治疗[42]。

颗粒链球菌属细菌药物敏感性测试操作技术要求高,结果也不够准确,相应报道往往缺乏一致性[45-47]。CLSI提出,临床工作者首先应按照指南推荐方案治疗颗粒链球菌属细菌所致感染性心内膜炎,只有特殊病例需要时才进行药敏测试。一项研究[48]调查了临床分离的109株毗邻颗粒链菌的抗菌药物敏感性,毗邻颗粒链菌对青霉素的敏感率为34%,对头孢曲松、头孢噻肟的敏感率分别为22%、10%,对头孢吡肟的敏感率是3%,对美罗培南的敏感率为87%,对左氧氟沙星的敏感率为97%,对克林霉素、红霉素的敏感率分别为50%、80%,所有分离株均对万古霉素敏感。本研究结果亦显示,毗邻颗粒链菌对青霉素、头孢菌素、碳青霉烯类、氟喹诺酮类、大环内酯类均呈现不同程度耐药,未发现对万古霉素耐药的菌株。

综上所述,本研究发现我国血标本临床分离毗邻颗粒链菌检出率呈上升趋势,该菌对青霉素、头孢菌素、碳青霉烯类、氟喹诺酮类、大环内酯类均可出现耐药情况,但未发现对万古霉素耐药的菌株。因此,血培养阳性、经革兰染色呈短链或成对状的阳性球菌或球杆菌(部分菌体细胞可呈典型的杆菌形态),在血平板上不生长或生长缓慢,微生物工作者应考虑可能为颗粒链球菌,可以加做卫星试验,有条件的实验室可以应用16S rRNA基因测序技术辅助鉴定,在血平板中加入盐酸吡哆醛可以促进这些细菌的生长。虽然颗粒链球菌的耐药性逐渐增加,但青霉素联合庆大霉素仍然是通常推荐的治疗方法。对临床工作者而言,尽早认识并检出颗粒链球菌,根据患者感染的具体因素选用合适的抗菌药物和适当的手术管理,必要时进行药敏检测,并根据治疗情况延长抗感染疗程,再加上密切的临床随访和炎症标志物监测,将有助于临床及时诊断和治疗,有望提高毗邻颗粒链菌血流感染的早期诊断率,降低毗邻颗粒链菌血流感染的病死率。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Frenkel A, Hirsch W. Spontaneous development of L forms of Streptococci requiring secretions of other bacteria or sulphydryl compounds for normal growth[J]. Nature, 1961, 191: 728-730. DOI:10.1038/191728a0 |

| [2] |

Carleo MA, Del Giudice A, Viglietti R, et al. Aortic valve endocarditis caused by Abiotrophia defectiva: case report and literature overview[J]. In Vivo, 2015, 29(5): 515-518. |

| [3] |

Christensen JJ, Facklam RR. Granulicatella and Abiotrophia species from human clinical specimens[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2001, 39(10): 3520-3523. DOI:10.1128/JCM.39.10.3520-3523.2001 |

| [4] |

Brouqui P, Raoult D. Endocarditis due to rare and fastidious bacteria[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2001, 14(1): 177-207. DOI:10.1128/CMR.14.1.177-207.2001 |

| [5] |

Lin CH, Hsu RB. Infective endocarditis caused by nutritionally variant Streptococci[J]. Am J Med Sci, 2007, 334(4): 235-239. DOI:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3180a6eeab |

| [6] |

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk susceptibility testing of infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria: M45 3rd ed[S]. Malvern, PA, USA: CLSI, 2015.

|

| [7] |

Minces LR, Shields RK, Sheridan K, et al. Peptostreptococcus infective endocarditis and bacteremia. Analysis of cases at a tertiary medical center and review of the literature[J]. Anaerobe, 2010, 16(4): 327-330. DOI:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.03.011 |

| [8] |

Slipczuk L, Codolosa JN, Davila CD, et al. Infective endocarditis epidemiology over five decades: a systematic review[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(12): e82665. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0082665 |

| [9] |

Wijetunga M, Bello E, Schatz I. Abiotrophia endocarditis: a case report and review of literature[J]. Hawaii Med J, 2002, 61(1): 10-12. |

| [10] |

Brouqui P, Raoult D. New insight into the diagnosis of fastidious bacterial endocarditis[J]. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol, 2006, 47(1): 1-13. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00054.x |

| [11] |

Bizzarro MJ, Callan DA, Farrel PA, et al. Granulicatella adiacens and early-onset sepsis in neonate[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2011, 17(10): 1971-1973. DOI:10.3201/eid1710.101967 |

| [12] |

Woo PCY, Fung AMY, Lau SKP, et al. Granulicatella adiacens and Abiotrophia defectiva bacteraemia characterized by 16S rRNA gene sequencing[J]. J Med Microbiol, 2003, 52(Pt 2): 137-140. |

| [13] |

Chang SH, Lee CC, Chen SY, et al. Infectious intracranial aneurysms caused by Granulicatella adiacens[J]. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 2008, 60(2): 201-204. DOI:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.09.002 |

| [14] |

Senn L, Entenza JM, Greub G, et al. Bloodstream and endovascular infections due to Abiotrophia defectiva and Granulicatella species[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2006, 6: 9. DOI:10.1186/1471-2334-6-9 |

| [15] |

Vandana KE, Mukhopadhyay C, Rau NR, et al. Native valve endocarditis and femoral embolism due to Granulicatella adiacens: a rare case report[J]. Braz J Infect Dis, 2010, 14(6): 634-636. DOI:10.1016/S1413-8670(10)70124-0 |

| [16] |

Shailaja TS, Sathiavathy KA, Unni G. Infective endocarditis caused by Granulicatella adiacens[J]. Indian Heart J, 2013, 65(4): 447-449. DOI:10.1016/j.ihj.2013.06.014 |

| [17] |

Ruoff KL. Nutritionally variant Streptococci[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 1991, 4(2): 184-190. DOI:10.1128/CMR.4.2.184 |

| [18] |

Stein DS, Nelson KE. Endocarditis due to nutritionally deficient Streptococci: therapeutic dilemma[J]. Rev Infect Dis, 1987, 9(5): 908-916. DOI:10.1093/clinids/9.5.908 |

| [19] |

Altay M, Akay H, Yildiz E, et al. A novel agent of peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis: Granulicatella adiacens[J]. Perit Dial Int, 2008, 28(1): 96-97. DOI:10.1177/089686080802800116 |

| [20] |

Cincotta MC, Coffey KC, Moonah SN, et al. Case report of Granulicatella adiacens as a cause of bacterascites[J]. Case Rep Infect Dis, 2015, 2015: 132317. |

| [21] |

Hepburn MJ, Fraser SL, Rennie TA, et al. Septic arthritis caused by Granulicatella adiacens: diagnosis by inoculation of synovial fluid into blood culture bottles[J]. Rheumatol Int, 2003, 23(5): 255-257. DOI:10.1007/s00296-003-0305-4 |

| [22] |

Bauer T, Maman L, Matha C, et al. Dental care and joint prostheses[J]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot, 2007, 93(6): 607-618. DOI:10.1016/S0035-1040(07)92685-9 |

| [23] |

Rosenthal O, Woywodt A, Kirschner P, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis and endocarditis of a pacemaker lead due to Granulicatella (Abiotrophia) adiacens[J]. Infection, 2002, 30(5): 317-319. DOI:10.1007/s15010-002-2104-3 |

| [24] |

York J, Fisahn C, Chapman J. Vertebral osteomyelitis due to Granulicatella adiacens, a nutritionally variant Streptococci[J]. Cureus, 2016, 8(9): e808. |

| [25] |

Del Pozo JL, Garcia-Quetglas E, Hernaez S, et al. Granulicatella adiacens breast implant-associated infection[J]. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 2008, 61(1): 58-60. DOI:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.12.009 |

| [26] |

Riede U, Graber P, Ochsner PE. Granulicatella (abiotrophia) adiacens infection associated with a total knee arthroplasty[J]. Scand J Infect Dis, 2004, 36(10): 761-764. DOI:10.1080/00365540410021009a |

| [27] |

Levin YD, Petronaci CL. Isolation of Abiotrophia/Granulicatella species from a brain abscess in an adult patient without prior history of neurosurgical instrumentation[J]. South Med J, 2010, 103(4): 386-387. |

| [28] |

Purohit G, Mishra B, Sahoo S, et al. Granulicatella adiacens as an unusual cause of empyema: a case report and review of literature[J]. J Lab Physicians, 2022, 14(3): 343-347. DOI:10.1055/s-0042-1744236 |

| [29] |

Cerceo E, Christie JD, Nachamkin I, et al. Central nervous system infections due to Abiotrophia and Granulicatella species: an emerging challenge?[J]. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 2004, 48(3): 161-165. DOI:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2003.10.009 |

| [30] |

Zenone T, Durand DV. Brain abscesses caused by Abiotrophia defectiva: complication of immunosuppressive therapy in a patient with connective-tissue disease[J]. Scand J Infect Dis, 2004, 36(6/7): 497-499. |

| [31] |

Schlegel L, Merlet C, Laroche JM, et al. Iatrogenic meningitis due to Abiotrophia defectiva after myelography[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 1999, 28(1): 155-156. DOI:10.1086/517189 |

| [32] |

Keay L, Harmis N, Corrigan K, et al. Infiltrative keratitis associated with extended wear of hydrogel lenses and Abiotrophia defectiva[J]. Cornea, 2000, 19(6): 864-869. DOI:10.1097/00003226-200011000-00024 |

| [33] |

Namdari H, Kintner K, Jackson BA, et al. Abiotrophia species as a cause of endophthalmitis following cataract extraction[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 1999, 37(5): 1564-1566. DOI:10.1128/JCM.37.5.1564-1566.1999 |

| [34] |

Finegold SM, Flynn MJ, Rose FV, et al. Bacteriologic findings associated with chronic bacterial maxillary sinusitis in adults[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2002, 35(4): 428-433. DOI:10.1086/341899 |

| [35] |

Lopardo H, Hernández C. Extravascular infections caused by Granulicatella adiacens: two case-reports and review[J]. Clin Microbiol Newsl, 2004, 26(10): 78-80. |

| [36] |

Alberti MO, Hindler JA, Humphries RM. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Abiotrophia defectiva, Granulicatella adiacens, and Granulicatella elegans[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2015, 60(3): 1411-1420. |

| [37] |

Al-Jasser AM, Enani MA, Al-Fagih MR. Endocarditis caused by Abiotrophia defectiva[J]. Libyan J Med, 2007, 2(1): 43-45. DOI:10.3402/ljm.v2i1.4691 |

| [38] |

Pinkney JA, Nagassar RP, Roye-Green KJ, et al. Abiotrophia defectiva endocarditis[J]. BMJ Case Rep, 2014, 2014: bcr2014207361. DOI:10.1136/bcr-2014-207361 |

| [39] |

Cargill JS, Scott KS, Gascoyne-Binzi D, et al. Granulicatella infection: diagnosis and management[J]. J Med Microbiol, 2012, 61(Pt 6): 755-761. |

| [40] |

Gould FK, Denning DW, Elliott TSJ, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and antibiotic treatment of endocarditis in adults: a report of the Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2012, 67(2): 269-289. DOI:10.1093/jac/dkr450 |

| [41] |

Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the task force for the management of infective endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM)[J]. Eur Heart J, 2015, 36(44): 3075-3128. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319 |

| [42] |

Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association[J]. Circulation, 2015, 132(15): 1435-1486. DOI:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296 |

| [43] |

Padmaja K, Lakshmi V, Subramanian S, et al. Infective endocarditis due to Granulicatella adiacens: a case report and review[J]. J Infect Dev Ctries, 2014, 8(4): 548-550. DOI:10.3855/jidc.3689 |

| [44] |

Adam EL, Siciliano RF, Gualandro DM, et al. Case series of infective endocarditis caused by Granulicatella species[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2015, 31: 56-58. DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.10.023 |

| [45] |

Lejbkowicz F, Kassis I. Granulicatella and Abiotrophia species: cause or consequence?[J]. Clin Microbiol Newsl, 2002, 24(16): 125-127. DOI:10.1016/S0196-4399(02)80032-0 |

| [46] |

Zheng XT, Freeman AF, Villafranca J, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of invasive pediatric Abiotrophia and Granulicatella isolates[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2004, 42(9): 4323-4326. DOI:10.1128/JCM.42.9.4323-4326.2004 |

| [47] |

Liao CH, Teng LJ, Hsueh PR, et al. Nutritionally variant streptococcal infections at a university hospital in Taiwan: disease emergence and high prevalence of beta-lactam and macrolide resistance[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2004, 38(3): 452-455. DOI:10.1086/381098 |

| [48] |

Mushtaq A, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Cole NC, et al. Differential antimicrobial susceptibilities of Granulicatella adiacens and Abiotrophia defectiva[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2016, 60(8): 5036-5039. DOI:10.1128/AAC.00485-16 |