2. 南京大学医学院附属金陵医院重症医学科, 江苏 南京 210002

2. Department of Critical Care Medicine, Affiliated Jinling Hospital of Medical School of Nanjing University, Nanjing 210002, China

急性胰腺炎(acute pancreatitis, AP)是由多种病因引起的因胰酶异常激活消化胰腺自身及周围组织而引发的急腹症[1],其中20%的患者会伴发器官功能障碍和(或)胰腺坏死组织感染(infected pancreatic necrosis, IPN)进展为重症急性胰腺炎(severe acute pancreatitis, SAP),病死率高达20%~40%[2-4]。SAP患者存在诸多引发血流感染(bloodstream infection, BSI)的高危因素,如侵入性操作、免疫抑制状态、局灶性感染播散、医院感染、营养状况差等[5],易诱发脓毒症,加重器官功能障碍,严重影响患者的预后。因此,快速、准确识别BSI病原体是指导抗菌药物使用的关键。目前,血培养(blood culture, BC)是BSI诊断的金标准[6],但受其技术原理限制,存在阳性率低、耗时长、采血量大、易污染等缺点[7-8],难以实时辅助临床诊治。微滴数字聚合酶链反应(droplet digital PCR, ddPCR)作为第三代核酸扩增与检测技术,通过平行的单分子扩增实现待检靶分子载量值的绝对定量[9-11],能同时对病原体及耐药基因进行多重检测,具有快速、高灵敏度、不依赖标准曲线等优势[12],以及研究和临床应用前景。本研究基于SAP合并疑似BSI患者人群,评价ddPCR的病原学诊断效能,并探讨其临床应用价值。

1 对象与方法 1.1 研究对象选取2022年7—9月某院重症医学科收治的SAP患者,临床医生怀疑BSI发生时,在同一时间、同一部位采集患者静脉血标本。纳入标准包括(1)依据改良Atlanta标准诊断为SAP[13]。(2)年龄≥18岁。(3)至少符合两项全身炎症反应综合征(SIRS)标准:a)最高体温>38℃或<36℃;b)心率>90次/min;c)呼吸>20次/min或PaCO2<32 mmHg;d)白细胞计数>12.0×109/L或<4.0×109/L。排除标准包括(1)拒绝抽血检测;(2)病历资料不完整。本研究方案经该医院医学伦理委员会批准(批号:2021NZKY-014-01),纳入受试者均签署知情同意书。

1.2 检测方法 1.2.1 BC法按规范流程采集2套血标本并送至微生物实验室[6],使用血培养仪(BD BactecTM FX40, 美国)按使用手册对血标本进行分析,使用Vitek®MS系统(BioMerieux, version 1.7, 法国)对培养阳性血标本进行菌种鉴定,并进行药物敏感试验(antimicrobial susceptibility testing, AST)。

1.2.2 ddPCR法按规范流程采集5~10 mL静脉血于EDTA抗凝管中,2 h内离心(3 000 r/min,15 min)后采集血浆。依次取60 μL洗脱液、2 mL血浆、10 μL内对照、200 μL蛋白酶K加至提取槽并置于核酸提取仪进行核酸提取,收集洗脱液并以5 μL/管加入至含靶标的预混液试剂管中,放于标本制备仪(DG32,领航基因科技,中国)进行液滴制备,使用PCR扩增仪(TC1,领航基因科技,中国)按照“95℃ 5 min; (95℃ 5 s,60℃ 20 s) ×40循环; 25℃ 5 min”循环参数进行平行扩增,最后使用生物芯片阅读仪(CS7,领航基因科技,中国)分析并报告病原体和耐药基因型的类别及载量值。

1.2.3 ddPCR检测范围检测范围包括15种病原体及5种耐药基因,分别为铜绿假单胞菌、阴沟肠杆菌、肺炎克雷伯菌、大肠埃希菌、鲍曼不动杆菌、金黄色葡萄球菌、凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌、肠球菌、链球菌、念珠菌、嗜麦芽窄食单胞菌、柠檬酸杆菌、黏质沙雷菌、奇异变形杆菌、洋葱伯克霍尔德菌,以及耐药基因blaKPC、mecA、blaNDM/IMP、blaOXA-48、VanA/VanM。

1.3 数据收集通过电子病历系统收集患者的年龄、性别、身体质量指数(BMI)、AP病因、首次检测距发病日数、首次检测当日器官功能支持情况,收集两种检测方法的结果及从上机至报告最终结果的耗时,每次检测当日的病情严重度评分,以及实验室指标、检测前1周内的其他体液细菌培养结果等。

1.4 检测结果解读如果检测到一种或多种病原体认定为阳性结果,没有检测到病原体认定为阴性结果。如果单次检测两种方法均为阴性或ddPCR检测菌种等同/包含BC结果,定义为结果一致;BC呈阳性,ddPCR呈阴性或检测菌种不等同/不包含BC结果,ddPCR结果定义为假阴性;当BC呈阴性,ddPCR呈阳性,则判定为可能血流感染或推定假阳性。可能血流感染是指ddPCR结果与检测前1周内非血标本病原学检测结果相符;推定假阳性是指ddPCR结果与检测前1周内非血标本病原学检测结果不相符[14]。AST阳性是指下述情况:AST显示对亚胺培南或美罗培南耐药,定义为碳青霉烯类耐药,对应ddPCR耐药基因型为blaKPC、blaNDM/IMP、blaOXA-48;AST显示对甲氧西林耐药,对应ddPCR耐药基因mecA;AST显示对万古霉素耐药,对应ddPCR耐药基因为VanA/VanM。

1.5 统计学分析应用SPSS 25.0软件进行统计分析,计量资料采用均值±标准差(x±s)描述,计数资料采用频数(率)描述;计算ddPCR检测的灵敏度、特异度、阳性预测值和阴性预测值;采用Spearman相关性分析计算ddPCR单次检测病原体载量与感染指标水平的相关性;双侧P≤0.05为差异有统计学意义。应用Graphpad Prism 9.0.0软件进行图绘制。

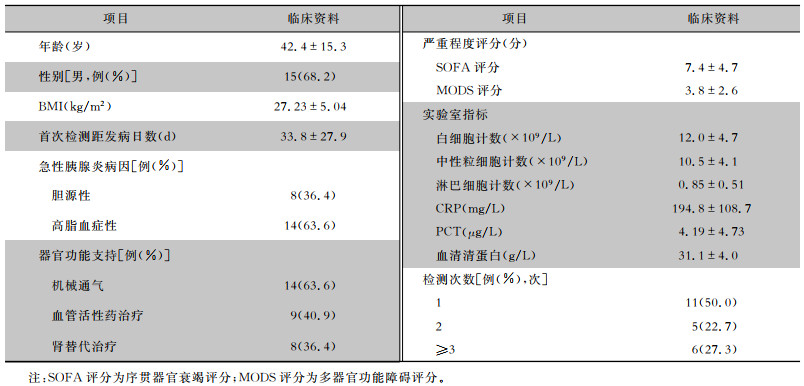

2 结果 2.1 一般资料本研究共纳入22例患者,年龄18~69岁,平均(42.4±15.3)岁,男性15例(68.2%),首次检测时患者的平均C反应蛋白(CRP)和降钙素原(PCT)值分别为194.8 mg/L、4.19 μg/L。见表 1。共送检血标本52份,ddPCR耗时[(0.16±0.03)d]低于BC耗时[(5.92±1.20)d;P<0.001]。

| 表 1 22例SAP患者一般资料与临床特征 Table 1 General data and clinical characteristics of 22 SAP patients |

|

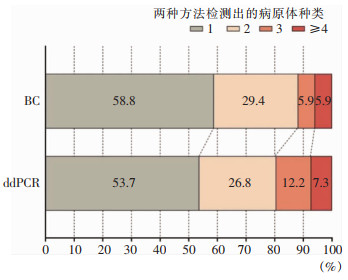

52份血标本中,BC阳性17份(32.7%),分离病原体29株,以凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌、鲍曼不动杆菌、肺炎克雷伯菌为主;ddPCR检测阳性41份(78.8%),检出病原体73株,以肺炎克雷伯菌、鲍曼不动杆菌、肠球菌为主。ddPCR检测前7日内患者引流液、痰、胆汁等34份体液标本的细菌培养结果显示,共分离病原体51株。见图 1。41.2%的BC阳性及46.3%的ddPCR阳性血标本中检测到两种及以上病原体。见图 2。

|

| 图 1 SAP患者血标本BC、ddPCR检测及非血标培养病原菌分布情况 Figure 1 Pathogen distribution of blood specimens from SAP patients by BC and ddPCR as well as non-blood specimens by bacterial culture |

|

| 图 2 ddPCR和BC单次检测出病原体种类分布 Figure 2 Distribution of pathogen species in single detection by ddPCR and BC |

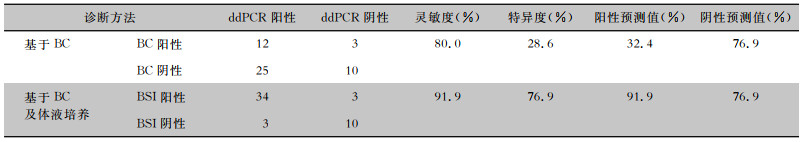

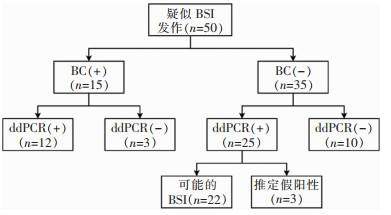

在ddPCR检测范围内,共有50份血标本检测结果纳入诊断效能的计算,排除的2份血标本BC检测结果为恶臭假单胞菌和食酸代夫特菌,不在ddPCR检测范围内。以BC为金标准,两种方法一致阳性12份,一致阴性10份,总体一致性为44.0%(22/50),ddPCR的灵敏度为80.0%(12/15),特异度为28.6%(10/35),阳性预测值和阴性预测值分别为32.4%(12/37)、76.9%(10/13);在考虑可能BSI之后,ddPCR的灵敏度为91.9%(34/37),特异度为76.9%(10/13),阳性预测值和阴性预测值分别为91.9%(34/37)、76.9%(10/13)。见表 2、图 3。

| 表 2 ddPCR在病原学诊断中的效能 Table 2 Efficacy of ddPCR in etiological diagnosis |

|

|

| 注:+表示阳性;-表示阴性。 图 3 目标范围内ddPCR和BC的检测情况及结果 Figure 3 Detection results of ddPCR and BC in targeted range |

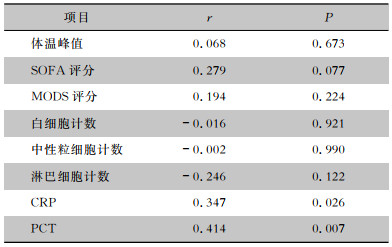

相关性分析显示,在ddPCR检出的阳性血标本中,病原菌载量值与检测当日的CRP、PCT水平呈正相关(均P<0.05),与检测当日的体温峰值、SOFA评分、MODS评分、白细胞计数、中性粒细胞计数、淋巴细胞计数均未见明显相关性(均P>0.05)。见表 3。

| 表 3 病原菌载量与感染指标的相关性 Table 3 Correlation between pathogen load and inflammatory parameters |

|

17份BC阳性的血标本中12份AST阳性。41份ddPCR阳性血标本中28份检出耐药基因,其中blaKPC阳性19份,blaNDM/IMP阳性9份,VanA/VanM阳性6份,mecA阳性5份。6份ddPCR检出VanA/VanM基因的血标本中,5份(83.3%)肠球菌阳性;5份检出mecA基因的血标本中,4份(80.0%)葡萄球菌阳性。12份AST阳性血标本中,ddPCR耐药基因检测阳性9份(75.0%),其中8份(66.7%)耐药基因结果等同或包含AST结果,不一致的4份标本中存在2份漏检,2份未在ddPCR检测范围内。

3 讨论BSI是世界范围内一个重要的公共卫生问题,延迟的感染源控制与不充分的抗感染治疗会显著增加患者死亡风险并影响长期预后[15-17]。2021年《脓毒症和脓毒症休克管理国际指南》强调:对于可能患有脓毒症或脓毒症休克的成人,应在1 h内给予抗菌药物[18]。由于BSI的症状缺乏特异性、BC阳性率低及存在滞后性,在BSI病原学早期诊断、感染程度分层、抗菌药物精准使用及疗效监测等方面存在诸多困难。

ddPCR作为一种新兴的分子诊断技术,不依赖标准曲线即可对目标序列进行绝对定量检测[12],目前已广泛应用于无创产前基因检测和肿瘤的液体活检[19-20];同时,在感染性疾病的诊断中也显示出了巨大潜力[21]。本研究显示,ddPCR在耗时方面明显优于BC,此为BSI病原学早期诊断,精准指导抗菌药物使用提供了可能;同时,包括AP在内的许多无菌性炎症在发病早期具有发热、炎症指标升高等易与感染相混淆的表现[22],ddPCR的使用将有助于临床医生对其进行鉴别。考虑到BC存在一定假阴性率[23],本研究整合了检测前1周内非血标本细菌培养结果来综合判定BSI的可能,使ddPCR的灵敏度和特异度分别提升至91.9%、76.9%,与既往研究[24]报道一致。值得注意的是,ddPCR和BC在2份血标本中均检测到念珠菌,并且既往研究[14, 25]也证实了ddPCR对于真菌的诊断性能。

BC阳性血标本中,有3份ddPCR检测为阴性,在既往研究[21, 26]中有类似报道,结合BC常见污染菌分布[6],考虑其中2份血标本BC分离的溶血性葡萄球菌为采样时混入的皮肤定植菌;另外1份血标本BC分离出多种细菌,ddPCR漏检了其中的黏质沙雷菌和阴沟肠杆菌,笔者认为可能是由于ddPCR检测血浆中病原体DNA片段,存在DNA突变或在菌种过多时存在相互干扰的情况,进而影响检测的精准度,还需要更多的基础研究来证实。

在过去几十年中,有250余种脓毒症相关生物标志物被研究用于辅助临床决策[18, 27],CRP和PCT等作为当前研究和应用最广泛的生物标志物,一定程度上反映了机体对病原体的免疫反应强度[28]。本研究显示了ddPCR阳性血标本中病原菌DNA载量值与检测当日的CRP和PCT水平呈明显的正相关关系,表明ddPCR在检测出病原体种类的同时,也能较直观地反映感染的严重程度[29-30];并且,凭借其绝对定量的特性,为抗感染疗效的动态监测提供可能[31]。

近年来,不断有新兴的检测方法应用于感染病原学领域[8, 32-33],其中,宏基因组二代测序(meta-genomic next-generation sequencing, mNGS) 应用广泛并在脓毒症、中枢神经系统感染、组织感染等感染性疾病的病原体检测中逐渐受到认可[34-36]。有研究[37]比较了mNGS与ddPCR对于BSI的诊断效能,结果表明在ddPCR检测范围内,ddPCR具有更高的灵敏度和更短的检测耗时,然而mNGS具有更广的检测范围,并且在罕见病原体的诊断上具有优势。笔者认为,ddPCR在应用方面还需考虑以下几点:首先,基于检测血浆中微生物游离DNA(mcfDNA)的方法[38],ddPCR受病原体生存状况影响小,使其在检测中具有稳定性和可重复性,但无法区分血液中的病原菌处于存活或失活状态;同时,尚缺少病原菌DNA载量值定义BSI临床诊断及判定抗菌药物最佳启动时机阈值的相关研究。其次,尽管本研究在ddPCR检测的多数血标本中呈现了菌种与耐药基因型的对应关系,但ddPCR检测出的耐药基因型不等同于表型,且在多种病原菌感染时较难确定耐药基因源于何种病原菌,使其在指导抗感染药物使用时存在一定局限性。因此,如何将ddPCR更好地应用到临床实践中还需要更多高质量的前瞻性研究来明确。

本研究存在一定局限性。首先,该研究是在单中心进行的,作为探索性研究样本量较小;其次,未能评价和探讨ddPCR在动态监测个体抗感染疗效、改善患者预后方面的效能。

综上所述,ddPCR作为一种辅助BC诊断BSI的检测方法具有灵敏度高、耗时低等优势,对BSI病原体及耐药基因的快速检测具有一定的诊断意义,未来还需要更多前瞻性研究去探究其在指导抗菌药物使用、疗效动态监测及改善患者预后等方面的临床价值。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

中华医学会外科学分会胰腺外科学组. 中国急性胰腺炎诊治指南(2021)[J]. 中国实用外科杂志, 2021, 41(7): 739-746. Chinese Pancreatic Surgery Association, Chinese Society of Surgery, Chinese Medical Association. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of acute pancreatitis in China(2021)[J]. Chinese Journal of Practical Surgery, 2021, 41(7): 739-746. |

| [2] |

Boxhoorn L, Voermans RP, Bouwense SA, et al. Acute pancreatitis[J]. Lancet, 2020, 396(10252): 726-734. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31310-6 |

| [3] |

Petrov MS, Shanbhag S, Chakraborty M, et al. Organ failure and infection of pancreatic necrosis as determinants of mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis[J]. Gastroenterology, 2010, 139(3): 813-820. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.010 |

| [4] |

Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Boermeester MA, et al. Timing and impact of infections in acute pancreatitis[J]. Br J Surg, 2009, 96(3): 267-273. DOI:10.1002/bjs.6447 |

| [5] |

Timsit JF, Ruppé E, Barbier F, et al. Bloodstream infections in critically ill patients: an expert statement[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2020, 46(2): 266-284. DOI:10.1007/s00134-020-05950-6 |

| [6] |

中国医疗保健国际交流促进会临床微生物与感染分会, 中华医学会检验医学分会临床微生物学组, 中华医学会微生物学和免疫学分会临床微生物学组. 血液培养技术用于血流感染诊断临床实践专家共识[J]. 中华检验医学杂志, 2022, 45(2): 105-121. Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infection of China International Exchange and Promotion Association for Medical and Healthcare, Clinical Microbiology Group of the Laboratory Medicine Society of the Chinese Medical Association, Clinical Microbiology Group of the Microbiology and Immunology Society of the Chinese Medical Association. Chinese expert consensus on the clinical practice of blood culture in the diagnosis of bloodstream infection[J]. Chinese Journal of Laboratory Me-dicine, 2022, 45(2): 105-121. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn114452-20211109-00695 |

| [7] |

Zboromyrska Y, Cillóniz C, Cobos-Trigueros N, et al. Evaluation of the MagicpleTM sepsis real-time test for the rapid di-agnosis of bloodstream infections in adults[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2019, 9: 56. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2019.00056 |

| [8] |

Peri AM, Harris PNA, Paterson DL. Culture-independent detection systems for bloodstream infection[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2022, 28(2): 195-201. DOI:10.1016/j.cmi.2021.09.039 |

| [9] |

Quan PL, Sauzade M, Brouzes E. dPCR: a technology review[J]. Sensors (Basel), 2018, 18(4): 1271. DOI:10.3390/s18041271 |

| [10] |

Sreejith KR, Ooi CH, Jin J, et al. Digital polymerase chain reaction technology-recent advances and future perspectives[J]. Lab Chip, 2018, 18(24): 3717-3732. DOI:10.1039/C8LC00990B |

| [11] |

Salipante SJ, Jerome KR. Digital PCR-an emerging technology with broad applications in microbiology[J]. Clin Chem, 2020, 66(1): 117-123. DOI:10.1373/clinchem.2019.304048 |

| [12] |

Merino I, de la Fuente A, Domínguez-Gil M, et al. Digital PCR applications for the diagnosis and management of infection in critical care medicine[J]. Crit Care, 2022, 26(1): 63. DOI:10.1186/s13054-022-03948-8 |

| [13] |

Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, et al. Classification of acute pancreatitis-2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus[J]. Gut, 2013, 62(1): 102-111. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779 |

| [14] |

Nguyen MH, Clancy CJ, Pasculle AW, et al. Performance of the T2 bacteria panel for diagnosing bloodstream infections: a diagnostic accuracy study[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2019, 170(12): 845-852. DOI:10.7326/M18-2772 |

| [15] |

Tabah A, Koulenti D, Laupland K, et al. Characteristics and determinants of outcome of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections in intensive care units: the EUROBACT international cohort study[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2012, 38(12): 1930-1945. DOI:10.1007/s00134-012-2695-9 |

| [16] |

Adrie C, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Ibn Essaied W, et al. Attribu-table mortality of ICU-acquired bloodstream infections: Impact of the source, causative micro-organism, resistance profile and antimicrobial therapy[J]. J Infect, 2017, 74(2): 131-141. DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2016.11.001 |

| [17] |

McNamara JF, Righi E, Wright H, et al. Long-term morbidity and mortality following bloodstream infection: a systematic literature review[J]. J Infect, 2018, 77(1): 1-8. DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2018.03.005 |

| [18] |

Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021[J]. Crit Care Med, 2021, 49(11): e1063-e1143. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0000000000005337 |

| [19] |

Caswell RC, Snowsill T, Houghton JAL, et al. Noninvasive fetal genotyping by droplet digital PCR to identify maternally inherited monogenic diabetes variants[J]. Clin Chem, 2020, 66(7): 958-965. DOI:10.1093/clinchem/hvaa104 |

| [20] |

Boldrin E, Mazza M, Piano MA, et al. Putative clinical potential of ERBB2 amplification assessment by ddPCR in FFPE-DNA and cfDNA of gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma patients[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2022, 14(9): 2180. DOI:10.3390/cancers14092180 |

| [21] |

Wu J, Tang B, Qiu YZ, et al. Clinical validation of a multiplex droplet digital PCR for diagnosing suspected bloodstream infections in ICU practice: a promising diagnostic tool[J]. Crit Care, 2022, 26(1): 243. DOI:10.1186/s13054-022-04116-8 |

| [22] |

Leppäniemi A, Tolonen M, Tarasconi A, et al. 2019 WSES guidelines for the management of severe acute pancreatitis[J]. World J Emerg Surg, 2019, 14: 27. DOI:10.1186/s13017-019-0247-0 |

| [23] |

Murray PR, Masur H. Current approaches to the diagnosis of bacterial and fungal bloodstream infections in the intensive care unit[J]. Crit Care Med, 2012, 40(12): 3277-3282. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318270e771 |

| [24] |

Li M, Zhao LW, Zhu YJ, et al. Clinical value of droplet digi-tal PCR in the diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of suspected bacterial bloodstream infections[J]. Clin Chim Acta, 2023, 550: 117566. DOI:10.1016/j.cca.2023.117566 |

| [25] |

Chen B, Xie YG, Zhang N, et al. Evaluation of droplet digital PCR assay for the diagnosis of candidemia in blood samples[J]. Front Microbiol, 2021, 12: 700008. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2021.700008 |

| [26] |

Lin K, Zhao YH, Xu B, et al. Clinical diagnostic performance of droplet digital PCR for suspected bloodstream infections[J]. Microbiol Spectr, 2023, 11(1): e0137822. DOI:10.1128/spectrum.01378-22 |

| [27] |

Pierrakos C, Velissaris D, Bisdorff M, et al. Biomarkers of sepsis: time for a reappraisal[J]. Crit Care, 2020, 24(1): 287. DOI:10.1186/s13054-020-02993-5 |

| [28] |

van der Poll T, van de Veerdonk FL, Scicluna BP, et al. The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2017, 17(7): 407-420. DOI:10.1038/nri.2017.36 |

| [29] |

Rello J, Lisboa T, Lujan M, et al. Severity of pneumococcal pneumonia associated with genomic bacterial load[J]. Chest, 2009, 136(3): 832-840. DOI:10.1378/chest.09-0258 |

| [30] |

Waterer G, Rello J. Why should we measure bacterial load when treating community-acquired pneumonia?[J]. Curr Opin Infect Dis, 2011, 24(2): 137-141. DOI:10.1097/QCO.0b013e328343b70d |

| [31] |

Kustanovich A, Schwartz R, Peretz T, et al. Life and death of circulating cell-free DNA[J]. Cancer Biol Ther, 2019, 20(8): 1057-1067. DOI:10.1080/15384047.2019.1598759 |

| [32] |

Opota O, Jaton K, Greub G. Microbial diagnosis of bloodstream infection: towards molecular diagnosis directly from blood[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2015, 21(4): 323-331. DOI:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.02.005 |

| [33] |

上海市微生物学会临床微生物学专业委员会, 上海市医学会检验医学专科分会, 上海市医学会危重病专科分会. 血流感染临床检验路径专家共识[J]. 中华传染病杂志, 2022, 40(8): 457-475. Clinical Microbiology Division of Shanghai Society of Microbio-logy, Shanghai Society of Laboratory Medicine, Shanghai Medical Association, Shanghai Society of Critical Care Medicine, Shanghai Medical Association. Expert consensus on cli-nical laboratory strategies for bloodstream infection[J]. Chinese Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2022, 40(8): 457-475. |

| [34] |

Miller S, Chiu C. The role of metagenomics and next-generation sequencing in infectious disease diagnosis[J]. Clin Chem, 2021, 68(1): 115-124. DOI:10.1093/clinchem/hvab173 |

| [35] |

Hong DH, Wang P, Zhang JZ, et al. Plasma metagenomic next-generation sequencing of microbial cell-free DNA detects pathogens in patients with suspected infected pancreatic necrosis[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2022, 22(1): 675. DOI:10.1186/s12879-022-07662-2 |

| [36] |

凌勇, 胡雪姣, 赵越, 等. 宏基因组二代测序在骨关节感染病原学诊断中的应用[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2023, 22(5): 527-531. Ling Y, Hu XJ, Zhao Y, et al. Application of next-generation metagenomic sequencing in the etiological diagnosis of bone and joint infection[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2023, 22(5): 527-531. |

| [37] |

Hu BC, Tao Y, Shao ZQ, et al. A comparison of blood pathogen detection among droplet digital PCR, metagenomic next-generation sequencing, and blood culture in critically ill patients with suspected bloodstream infections[J]. Front Microbiol, 2021, 12: 641202. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2021.641202 |

| [38] |

Nie MY, Zheng M, Li CM, et al. Assembled step emulsification device for multiplex droplet digital polymerase chain reaction[J]. Anal Chem, 2019, 91(3): 1779-1784. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.8b04313 |