由于新生儿生理上不成熟,免疫系统尚未完全建立,皮肤黏膜定植菌易转变为致病菌[1-2],甚至发展为败血症[3]。新生儿败血症病死率高达15%,早期多无特异性临床表现[4],尤其是多重耐药菌定植的新生儿,一旦入血发展为败血症,将给治疗带来严重困难。了解新生儿入院时咽、脐部的细菌检出特点及耐药情况,有助于医院感染的预防与控制,提高抗菌药物科学管理水平[5]。本文对2017—2022年新型冠状病毒感染(简称新冠)疫情发生前后细菌检出变化进行分析,现报告如下。

1 对象与方法 1.1 研究对象选取某院2017—2022年所有入住新生儿病房的新生儿,来自该院产科手术室、产房、母婴同室以及儿科门急诊,主要病种为早产儿、低出生体重儿、极低出生体重儿、新生儿呼吸窘迫综合征、窒息、肺炎、湿肺、胎粪吸入综合征、呼吸暂停、糖尿病母亲新生儿、高胆红素血症、脐炎、泌尿道感染、喂养不当等。

1.2 分组根据新冠疫情的发生时间进行分组,按入院时间分为2017—2019年组(前三年),2020—2022年组(后三年)。

1.3 研究方法所有新生儿入院时第一时间进行咽拭子与脐拭子筛查。标本采集确保在抗菌药物使用前、严格遵照无菌操作技术进行,并在2 h内送微生物实验室进行细菌培养、分离及鉴定。标本采集与送检参照《临床微生物标本采集和送检指南》[6]。细菌鉴定采用法国梅里埃公司质谱仪VITEK-MS。采用回顾性调查方法,从Lis系统获得所有新生儿入院筛查的细菌鉴定结果。多重耐药菌判断标准采用国际专家建议[7]。

1.4 统计学方法应用SPSS 22.0进行统计分析。组间率的比较采用χ2检验,P≤0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

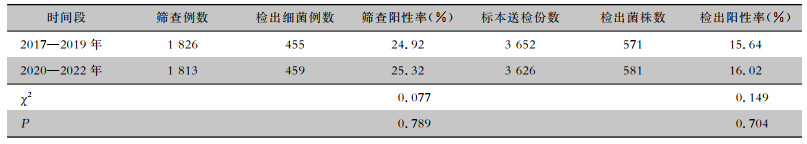

2 结果 2.1 基本情况2017—2022年共有新生儿3 639例,其中男性1 909例,女性1 730例,年龄最小为出生后10 min,最大为96 d(早产儿纠正胎龄未满28 d),年龄中位数2.0(3.0)d,住院日数中位数6.0(4.0)d。914例检出细菌,检出菌株1 152株,前三年与后三年的新生儿入院筛查阳性率、菌株检出阳性率比较,差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。见表 1。

| 表 1 2017—2019年与2020—2022年细菌检出情况 Table 1 Detection of bacteria in the years between 2017-2019 and 2020-2022 |

|

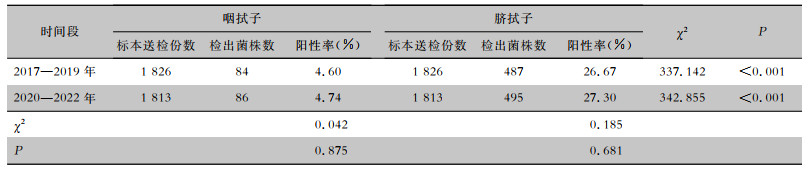

2017—2022年咽拭子检出菌株170株,脐拭子检出菌株982株;前三年与后三年的咽拭子与脐拭子细菌检出阳性率比较,差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05);但各时间段新生儿病房入院筛查脐拭子检出阳性率均高于咽拭子,差异均有统计学意义(均P<0.001),见表 2。

| 表 2 2017—2019年与2020—2022年不同部位细菌检出情况 Table 2 Detection of bacteria from different sites in the years between 2017-2019 and 2020-2022 |

|

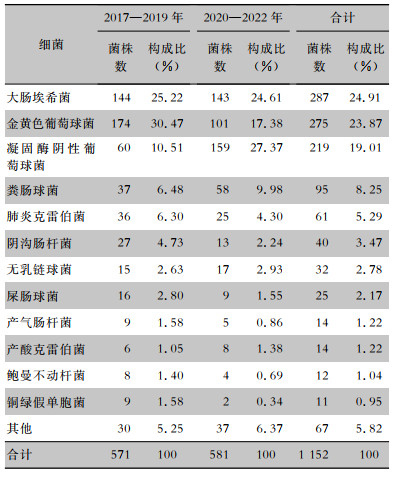

2017—2022年入院主动筛查共检出细菌1 152株,检出排名前五的细菌分别为大肠埃希菌(24.91%)、金黄色葡萄球菌(23.87%)、凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌(19.01%)、粪肠球菌(8.25%)及肺炎克雷伯菌(5.29%);2017—2019年与2020—2022年前三位细菌的排名并不一致。后三年金黄色葡萄球菌检出阳性率较前三年降低,从4.76%(174/3 652)下降至2.79%(101/3 626),差异有统计学意义(χ2=19.601,P<0.001);凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌检出阳性率升高,从1.64%(60/3 652)上升至4.38%(159/3 626),差异有统计学意义(χ2=46.875,P<0.001)。前后三年的金黄色葡萄球菌、凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌构成比比较,差异均有统计学意义(χ2值分别为27.149、53.160,均P<0.001)。见表 3。

| 表 3 2017—2019年与2020—2022年检出细菌分布情况 Table 3 Distribution of bacteria detected in the years between 2017-2019 and 2020-2022 |

|

2017—2022年3 639例入院行主动筛查的患者中69例检出多重耐药菌75株,其中65例患者检出耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌(MRSA)71株,有6例患者的咽部和脐部均检出MRSA。2017—2019年1 826例患者中有43例检出MRSA 48株,MRSA检出阳性率1.31%(48/3 652),2例检出耐碳青霉烯类铜绿假单胞菌(CRPA)各1株,1例检出耐万古霉素屎肠球菌(VRE-EFA)1株。2020—2022年1 813例患者中有22例检出MRSA 23株,MRSA检出阳性率0.63% (23/3 626),1例检出耐碳青霉烯类肺炎克雷伯菌(CRE-KPN)1株。后三年MRSA检出阳性率较前三年降低,差异有统计学意义(χ2=8.710,P<0.05)。

2.5 MRSA检出率2017—2019年入院筛查出的174株金黄色葡萄球菌中鉴定出MRSA 48株,MRSA检出率27.59%,2020—2022年101株金黄色葡萄球菌中鉴定出MRSA 23株,MRSA检出率22.77%。

2.6 不同筛查部位MRSA阳性率2017—2022年咽部检出MRSA 19株,阳性率0.52%,脐部检出MRSA 52株,阳性率1.43%。其中前三年脐部MRSA阳性率(2.25%,41/1 826)高于咽部(0.38%,7/ 1 826),差异有统计学意义(χ2=24.404,P<0.001)。脐部MRSA阳性率后三年(0.61%,11/1 813)较前三年降低(2.25%,41/1 826),差异有统计学意义(χ2=17.342,P<0.001)。

2.7 住院患者抗菌药物使用情况2017—2022年合计2 335例患者使用抗菌药物,住院患者抗菌药物使用率64.17%。后三年新生儿病房住院患者抗菌药物使用率为60.89%(1 104/1 813),低于前三年的67.42%(1 231/1 826),差异有统计学意义(χ2=16.828,P<0.001)。

3 讨论新生儿入院后第一时间予以咽部和脐部微生物筛查,可在最短的时间内获取细菌培养及鉴定结果,促进抗菌药物合理使用[8]。新生儿科医生无需盲目地给予所有住院新生儿预防性使用抗菌药物,通过进一步观察新生儿病情变化,结合临床实际情况判断致病菌或定植菌,是否需要给予抗感染或去定植治疗;对感染新生儿初始经验性治疗时可参考既往菌群检出与耐药情况选择抗菌药物,而后亦可对部分经验性治疗疗效不佳的患者依据细菌培养及药敏结果选择合适的抗菌药物;同时一旦筛查发现多重耐药菌,第一时间做好患者接触隔离,加强手卫生、环境清洁消毒等多重耐药菌集束化防控措施。而多重耐药菌如MRSA在医院内传播途径通常包括医护人员的手、患者使用过的器械、污染的环境[9],早期检测出多重耐药菌定植或感染新生儿,可有效控制其医院感染的传播和流行[10]。自2017年起,该院新生儿病房无多重耐药菌医院感染事件发生。

本研究结果显示,虽然该院新生儿病房在新冠疫情发生前三年(2017—2019年)与新冠疫情三年(2020—2022年) 总体细菌检出无较大差异,但进一步分析细菌检出构成比发现,在检出排名前五位的细菌中,金黄色葡萄球菌检出率下降,阳性率从4.76%降低至2.79%,构成比从30.47%下降至17.38%,排名从第一降至第三;而凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌检出增加,阳性率从1.64%上升至4.38%,构成比10.51%上升至27.37%,排名从第三上升至第一;检出的多重耐药菌主要为MRSA,新冠疫情三年期间新生儿入院脐部MRSA阳性率亦下降;MRSA检出率亦下降,与近年来全国细菌耐药监测报告中三级医院MRSA检出率变化趋势相仿[11];2017—2019年入院筛查MRSA检出率27.59%,2020—2022年入院筛查MRSA检出率22.77%,均低于CHINET公布的全国平均水平31.4%(2019年)、28.7%(2022年)[12]。与此同时住院患者抗菌药物使用率亦从67.42%下降至60.89%,与微生物送检指导治疗性抗菌药物使用情况相符。

金黄色葡萄球菌和凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌均是皮肤常见定植菌。凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌虽然毒力弱、致病力低,常为条件致病菌,但新生儿感染后会引起败血症[13]、脐炎[1]、原发性骨髓炎和感染性关节炎[14]、感染性心内膜炎[15]等,凝固酶阴性葡萄球菌败血症常发在早产儿,与低出生体重新生儿迟发性感染相关[16-17],严重时可导致新生儿死亡[18],应引起足够的重视。金黄色葡萄球菌毒力强、有多种毒力因子助其迅速传播成为重要的致病菌[19],尤其是MRSA,在某些特定人群中常引起感染暴发流行[20-21]。金黄色葡萄球菌可通过母体或环境接触等定植到新生儿[22],金黄色葡萄球菌在新生儿脐部残端定植率可达29.36%[23],亦可持续留在咽部[24],近年来,我国社区获得性MRSA感染在儿童中的发病率上升[25],尽管大多数社区获得性MRSA感染初始症状较轻、局限在皮肤和软组织[26-27],但也可能导致严重的、侵袭性和致死性的感染[28]。不良的个人卫生和感染控制措施可能是造成社区获得性MRSA感染传播的主要原因,手卫生是MRSA定植的主要危险因素[29],在社区加强手卫生宣教有助于减少社区获得性MRSA感染传播[30]。此外,在温暖、有限的空间内密切接触,亦可能会增加社区获得性MRSA感染的定植、感染和传播风险[31]。社区获得性MRSA感染通常在家庭和密切接触群体中传播,甚至可以通过公共交通传播,如果未去除传染源、阻断传播途径,还会反复感染[32]。在我国,“坐月子”是传统风俗,部分新生儿家庭可能存在新生儿居住空间相对密闭、家庭成员手卫生意识差、皮肤清洁不到位等情况。本研究发现,新冠疫情三年中新生儿入院筛查金黄色葡萄球菌及脐部MRSA阳性率下降,这可能与新冠疫情期间全民公共卫生意识有大幅提高相关[33],通过各级医疗机构、社区、学校以及各种媒体对各项感染防控措施不断宣教,促使全民保持更良好的个人卫生习惯,如佩戴口罩、勤洗手、加强开窗通风、保持居家环境清洁、减少人员流动等,这些措施在防控新冠疫情的同时,亦在不经意间去除了金黄色葡萄球菌传染源,阻断传播途径。

即便新冠疫情已过去,良好的个人卫生习惯应继续保持,新生儿医护人员可通过产前宣教、产科及新生儿病房出院宣教加强新生儿家庭成员的手卫生意识、适时开窗通风、保持居家环境清洁、避免人群聚集等综合防控措施来进一步降低金黄色葡萄球菌尤其是MRSA的传播。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

郑彩霞, 王晓晖, 钟馥霞, 等. 154例新生儿脐部感染原因分析及防护[J]. 中国妇幼保健, 2006, 21(6): 773-775. Zheng CX, Wang XH, Zhong FX, et al. Analysis of causes and prevention of umbilical infection in 154 newborns[J]. Maternal and Child Health Care of China, 2006, 21(6): 773-775. |

| [2] |

马艳, 张欢, 李芳. 新生儿脐部感染细菌定植的临床分析研究[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2015, 25(9): 2128-2130. Ma Y, Zhang H, Li F. Clinical study of bacterial colonization and umbilical infections in neonates[J]. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology, 2015, 25(9): 2128-2130. |

| [3] |

张小燕, 覃遵科, 王焕秀. 38例新生儿脐炎致败血症临床分析[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2001, 3(3): 283-284. Zhang XY, Qin ZK, Wang HX. Sepsis caused by omphalitis in 38 neonates[J]. Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics, 2001, 3(3): 283-284. |

| [4] |

张荣娜, 林华川, 蔡文红. 新生儿败血症早期临床诊断[J]. 中国妇幼保健, 2006, 21(24): 3452-3455. Zhang RN, Lin HC, Cai WH. Early diagnosis of neonatal septicemia[J]. Maternal and Child Health Care of China, 2006, 21(24): 3452-3455. |

| [5] |

国家卫生计生委, 国家发展改革委, 教育部, 等. 关于印发遏制细菌耐药国家行动计划(2016—2020年)的通知[J]. 中华人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会公报, 2016(8): 14-17. National Health and Family Planning Commission, National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Education, et al. Notice on issuing the national action plan for combating bacterial drug resistance(2016-2020)[J]. Gazette of the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, 2016(8): 14-17. |

| [6] |

中华预防医学会医院感染控制分会. 临床微生物标本采集和送检指南[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2018, 28(20): 3192-3200. Hospital Infection Control Branch of the Chinese Preventive Medicine Association. Guidelines for collection and submission of clinical microbial specimens[J]. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology, 2018, 28(20): 3192-3200. |

| [7] |

李春辉, 吴安华. MDR、XDR、PDR多重耐药菌暂行标准定义——国际专家建议[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2014, 13(1): 62-64. Li CH, Wu AH. Interim standard definition for MDR, XDR, and PDR multidrug-resistant bacteria-international expert recommendations[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2014, 13(1): 62-64. |

| [8] |

国家卫生健康委办公厅. 国家卫生健康委办公厅关于持续做好抗菌药物临床应用管理工作的通知[J]. 中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会公报, 2020(7): 21-22. General Office of the National Health Commission. Notice of the General Office of the National Health Commission on continuously improving the management of clinical application of antibiotics[J]. Gazette of the National Health Commission of People's Republic of China, 2020(7): 21-22. |

| [9] |

李春辉, 吴安华. 社区获得性耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌感染研究进展[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2008, 7(6): 430-434. Li CH, Wu AH. Research progress of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2008, 7(6): 430-434. |

| [10] |

Shirai Y, Arai H, Tamaki K, et al. Neonatal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection[J]. J Neonatal Perinatal Med, 2017, 10(4): 439-444. DOI:10.3233/NPM-16166 |

| [11] |

全国细菌耐药监测网. 全国细菌耐药监测网2014—2019年不同等级医院细菌耐药监测报告[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2021, 20(2): 95-111. China Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System. Surveillance on antimicrobial resistance of bacteria in different levels of hospitals: surveillance report from China Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System in 2014-2019[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2021, 20(2): 95-111. |

| [12] |

付强, 刘运喜, 霍瑞, 等. 医疗机构住院患者感染监测基本数据集及质量控制指标集实施指南(2021版)[M]. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2021. Fu Q, Liu YX, Huo R, et al. Implementation guidelines for the basic dataset and quality control indicator set of infection monitoring for inpatient patients in medical institutions (2021 edition)[M]. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2021. |

| [13] |

Hon KL, Li JJX, Cheng BLY, et al. Septicemia in a neonate following therapeutic hypothermia: the literature review of evi-dence[J]. Case Rep Pediatr, 2013, 2013: 514232. |

| [14] |

Eggink BH, Rowen JL. Primary osteomyelitis and suppurative arthritis caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci in a preterm neonate[J]. Pediatr Infect Dis J, 2003, 22(6): 572-573. |

| [15] |

Pearlman SA, Higgins S, Eppes S, et al. Infective endocarditis in the premature neonate[J]. Clin Pediatr (Phila), 1998, 37(12): 741-746. |

| [16] |

Filleron A, Simon M, Hantova S, et al. tuf-PCR-temporal temperature gradient gel electrophoresis for molecular detection and identification of staphylococci: application to breast milk and neonate gut microbiota[J]. J Microbiol Methods, 2014, 98: 67-75. |

| [17] |

罗芳, 章旭平, 温晓芳. 新生儿晚发型败血症病原菌及诊断方法[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2020, 30(18): 2825-2829. Luo F, Zhang XP, Wen XF. Pathogens isolated from neonates with late-onset sepsis and diagnosis methods[J]. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology, 2020, 30(18): 2825-2829. |

| [18] |

Venkatesh MP, Placencia F, Weisman LE. Coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections in the neonate and child: an update[J]. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis, 2006, 17(3): 120-127. |

| [19] |

张晓兵, 府伟灵. 群体感应与细菌毒力[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2011, 21(13): 2866-2870. Zhang XB, Fu WL. Quorum sensing and bacterial virulence[J]. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology, 2011, 21(13): 2866-2870. |

| [20] |

Montazeri EA, Khosravi AD, Jolodar A, et al. Identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains isolated from burn patients by multiplex PCR[J]. Burns, 2015, 41(3): 590-594. |

| [21] |

Young DM, Harris HW, Charlebois ED, et al. An epidemic of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus soft tissue infections among medically underserved patients[J]. Arch Surg, 2004, 139(9): 947-951. |

| [22] |

王红, 郁洁, 王博, 等. 住院新生儿鼻腔和体表定植金黄色葡萄球菌的分子特征及耐药性[J]. 中国循证儿科杂志, 2021, 16(5): 379-383. Wang H, Yu J, Wang B, et al. Molecular characteristics and antibiotic resistance of colonized Staphylococcus aureus at mucosal and skin surface in hospitalized neonates[J]. Chinese Journal of Evidence Based Pediatrics, 2021, 16(5): 379-383. |

| [23] |

张聪, 程慧, 侯明良, 等. 新生儿脐部目标性监测分析[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2010, 20(16): 2428-2430. Zhang C, Cheng H, Hou ML, et al. Targeted surveillance of newborn navel[J]. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology, 2010, 20(16): 2428-2430. |

| [24] |

Hamdan-Partida A, González-García S, de la Rosa García E, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus can persist in the throat[J]. Int J Med Microbiol, 2018, 308(4): 469-475. |

| [25] |

胡英惠, 甄景慧, 赵德环. 小儿社区获得性耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌感染临床分析[J]. 中国当代儿科杂志, 2006, 8(4): 298-300. Hu YH, Zhen JH, Zhao DH. Characteristics of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in children[J]. Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics, 2006, 8(4): 298-300. |

| [26] |

Dietrich DW, Auld DB, Mermel LA. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in southern New England children[J]. Pediatrics, 2004, 113(4): e347-e352. |

| [27] |

Sarkissian EJ, Gans I, Gunderson MA, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus musculoskeletal infections: emerging trends over the past decade[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 2016, 36(3): 323-327. |

| [28] |

陆敏, 张育才, 陆权. 儿童社区获得性耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌感染研究进展[J]. 国际儿科学杂志, 2009, 36(4): 376-379. Lu M, Zhang YC, Lu Q. Progress of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in children[J]. International Journal of Pediatrics, 2009, 36(4): 376-379. |

| [29] |

Alzahrani KJ, Eed EM, Alsharif KF, et al. Prevalence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Taif social correctional center, Saudi Arabia[J]. J Infect Dev Ctries, 2021, 15(12): 1861-1867. |

| [30] |

Golding GR, Quinn B, Bergstrom K, et al. Community-based educational intervention to limit the dissemination of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Northern Saskatchewan, Canada[J]. BMC Public Health, 2012, 12: 15. |

| [31] |

Cloran FJ. Cutaneous infections with community-acquired MRSA in aviators[J]. Aviat Space Environ Med, 2006, 77(12): 1271-1274. |

| [32] |

Yamamoto T, Nishiyama A, Takano T, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: community transmission, pathogenesis, and drug resistance[J]. J Infect Chemother, 2010, 16(4): 225-254. |

| [33] |

Mimura T, Matsumoto G, Natori T, et al. Impact of the COVID -19 pandemic on the incidence of surgical site infection after orthopaedic surgery: an interrupted time series analysis of the nationwide surveillance database in Japan[J]. J Hosp Infect, 2023, S0195-6701(23)00170-6. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2023.06.001 |