2. 大足区人民医院感染科,重庆 402360

唑和氨苄西林高度耐药。尿路感染复发前后ESBLs-UPEC对抗菌药物的敏感率比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。469株ESBLs-UPEC中90.4%的菌株携带毒力因子fimH,毒力因子sfaDE检出率最低,为8.3%;不同的毒力因子数量、组合方式与尿路感染复发之间无明显的相关性(P>0.05);复发≥3次组患者尿路感染分离的ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子iucD携带率较高(P=0.008);相同性别、年龄阶段复发组和未复发组患者尿路感染分离的ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子携带率比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);绝经后女性患者,复发组ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子kps MT Ⅱ携带率高于未复发组(61.7% VS 45.6%,P=0.037)。结论 ESBLs-UPEC菌株耐药较严重。ESBLs-UPEC携带最多的毒力因子为fimH,尿路感染复发≥3次患者分离的ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子iucD携带率较高,而绝经后女性复发尿路感染患者分离的ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子kps MT Ⅱ携带率较高。

唑和氨苄西林高度耐药。尿路感染复发前后ESBLs-UPEC对抗菌药物的敏感率比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。469株ESBLs-UPEC中90.4%的菌株携带毒力因子fimH,毒力因子sfaDE检出率最低,为8.3%;不同的毒力因子数量、组合方式与尿路感染复发之间无明显的相关性(P>0.05);复发≥3次组患者尿路感染分离的ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子iucD携带率较高(P=0.008);相同性别、年龄阶段复发组和未复发组患者尿路感染分离的ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子携带率比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05);绝经后女性患者,复发组ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子kps MT Ⅱ携带率高于未复发组(61.7% VS 45.6%,P=0.037)。结论 ESBLs-UPEC菌株耐药较严重。ESBLs-UPEC携带最多的毒力因子为fimH,尿路感染复发≥3次患者分离的ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子iucD携带率较高,而绝经后女性复发尿路感染患者分离的ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子kps MT Ⅱ携带率较高。2. Department of Infectious Diseases, The People's Hospital of Dazu District, Chongqing 402360, China

尿路感染是病原体直接侵入泌尿道,在尿液中生长繁殖并侵犯泌尿道黏膜或组织而引起的炎症反应。复发性尿路感染(recurrent urinary tract infection, rUTI)则是指6个月内发生2次及以上,或1年内发生3次以上的尿路感染。大肠埃希菌是目前尿路感染(urinary tract infection, UTI)最主要的致病菌之一(约占60%)[1-2]。近年来由于产超广谱β-内酰胺酶尿源性大肠埃希菌(ESBLs-UPEC)感染率居高不下[3-4],且ESBLs-UPEC携带的多种毒力因子有助于其黏附、结合、定植泌尿系上皮细胞,并入侵、干扰宿主免疫系统[5],因此ESBLs-UPEC导致的UTI高复发性成为了困扰患者和临床医生的难题。既往研究探索了临床症状、ST131分离株、肠道定植和膀胱印记等与尿路感染复发的相关性[6-9],而复发与ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子的关系尚少有报道。本研究通过检测ESBLs-UPEC携带的毒力因子,探索其与尿路感染复发之间的关系。

1 对象与方法 1.1 研究对象选取2019年1月—2021年9月重庆医科大学附属第一医院和大足区人民医院的尿路感染患者。纳入标准[10]为:(1)患者有尿频、尿急、尿痛等相应临床症状,且尿常规检查尿沉渣白细胞≥10个/高倍镜视野;(2)患者尿培养结果中病原菌≤2种,且细菌计数≥105 CFU/mL。排除标准[10]为:(1)患有糖尿病、尿路结石或存在泌尿生殖道解剖结构异常的患者;(2)泌尿道留置导尿管患者;(3)妊娠期妇女和近3个月有备孕需求的女性患者。对符合纳入标准的患者进行6个月随防,将6个月内复发ESBLs-UPEC感染的患者作为复发组,并记录复发次数,将6个月内未复发尿路感染的患者作为未复发组。两所医院共同完成患者信息的收集、菌种鉴定、药敏试验和随访,所有ESBLs-UPEC菌株均于重庆医科大学附属第一医院进行毒力因子的检测并进行数据整理和分析。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 标本采集参照《临床微生物学尿培养操作规范》,排除用药后尿液或避开血药高峰取样,嘱患者使用灭菌纱布蘸取清洁肥皂水清洗外阴和尿道口后,无菌尿杯留取清晨首次清洁中段尿。尿标本采集后立即送检(时间≤2 h)。对患者的尿标本同时用三个培养基进行培养,以排除操作过程中可能的污染,最后选择三个培养基中菌株长势最好的作为后续研究用菌株。

1.2.2 细菌鉴定和药敏试验采用美国临床实验室标准化协会(the Clinical and Laboratory Stan-dards Institute,CLSI)的30 μg头孢噻肟和头孢他啶双碟扩散试验(double disc diffusion test)进行ESBLs确证试验:在涂布大肠埃希菌的MH琼脂培养基中贴上头孢噻肟(30 μg)与头孢噻肟/克拉维酸(30 μg/10 μg)、头孢他啶(30 μg)与头孢他啶/克拉维酸(30 μg/10 μg)两组纸片,各纸片相距25 mm,35℃孵育18~20 h后观察结果。两组纸片任意一组后者与前者抑菌环直径之差≥5 mm即判断为ESBLs阳性。用Vitek 2 Compact全自动细菌鉴定及药敏分析系统进行菌种鉴定和药敏试验,药敏试验加做纸片扩散法。质控菌株为大肠埃希菌ATCC 25922,药物敏感试验结果的判断根据2014年CLSI《抗菌药物敏感性试验执行标准》进行。

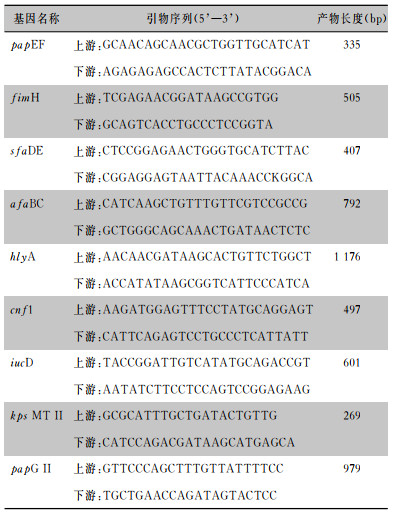

1.2.3 毒力因子的检测细菌基因组DNA抽提试剂盒提取ESBLs-UPEC的DNA,采用多重PCR方法对毒力因子进行扩增。扩增结束后取5 μL PCR扩增产物进行琼脂糖凝胶电泳分析(2%琼脂糖凝胶,加GoldView染料,电压120 V,时间35 min)。电泳结束后在凝胶成像系统下观察分析结果。引物序列见表 1。反应体系:DNA模板5 μL,2×PCR MasterMix 25 μL,上、下游引物各2 μL,加去离子水至50 μL。多重PCR反应参数:预变性93℃,3 min;变性94℃,30 s;退火55℃,30 s;延长72℃,60 s;共30个循环,再延长72℃,5 min。

| 表 1 毒力因子引物序列及扩增产物大小 Table 1 Primer sequences and amplification product size of virulence factors |

|

T100型PCR扩增仪(美国Bio-Rad公司),BioSpectrum 410型凝胶成像系统(美国UVP公司),DYCP-33A型琼脂糖水平核酸电泳仪(中国北京六一仪器厂),Vitek 2 Compact全自动细菌鉴定及药敏分析系统(法国梅里埃公司),PCR MasterMix,琼脂糖粉(北京索莱宝科技有限公司,批号: PC1150,A8201),DNA提取试剂盒[天根生化科技(北京)有限公司,批号: DP302],DNA分子标记物[中国生工生物工程(上海)股份有限公司,批号: B600333]。所有引物均由中国生工生物工程(上海)股份有限公司合成。

1.3 统计学分析应用SPSS 20.0软件进行统计学分析,计数资料以例数或百分比表示,采用卡方检验、Fisher确切概率法和Pearson相关性检验进行分析,以P≤0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2 结果 2.1 一般情况对2019年1月—2021年9月两所医院所有尿路感染患者进行尿培养和细菌药敏试验,共纳入600例(其中重庆医科大学附属第一医院381例,大足人民医院219例)ESBLs-UPEC感染的UTI患者,其中男性118例,女性482例;患者年龄19~86岁,平均(51±2.1)岁,其中<45岁257例(42.9%),45~60岁164例(27.3%),≥60岁179例(29.8%)。对纳入的患者进行了6个月随访,53例失访。发生复发者365例,排除78例非ESBLs-UPEC感染引起的复发者,最终287例纳入复发组,其中男性56例,女性231例,复发组中92例患者复发一次, 116例患者复发2次, 79例患者复发≥3次;182例纳入未复发组,其中男性36例,女性146例。

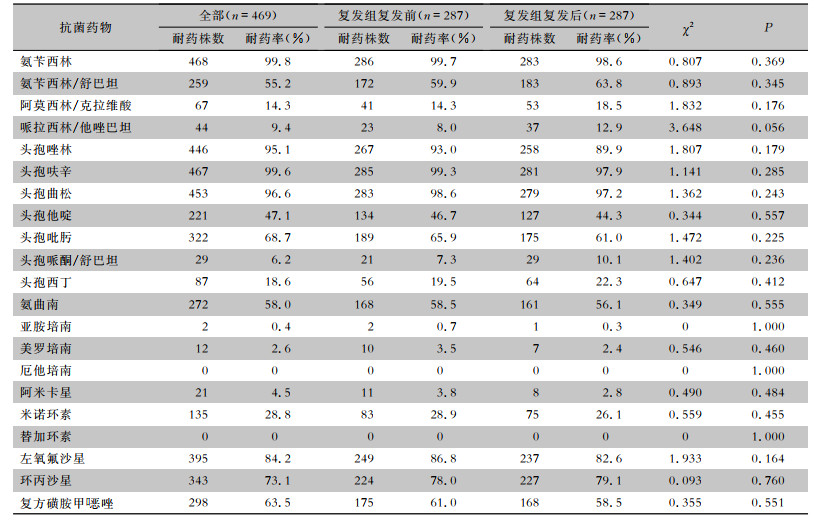

2.2 耐药情况469株ESBLs-UPEC对替加环素、厄他培南、阿米卡星、头孢哌酮/舒巴坦、哌拉西林/他唑巴坦耐药率较低,为0~9.4%,除对第二、三、四代头孢菌素和单酰胺类高度耐药外,对氨苄西林(99.8%)、左氧氟沙星(84.2%)和复方磺胺甲

| 表 2 ESBLs-UPEC对21种常用抗菌药物的耐药情况 Table 2 Resistance of ESBLs-UPEC to 21 commonly used antimicrobial agents |

|

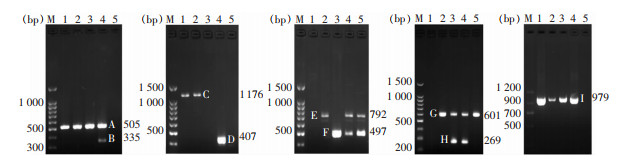

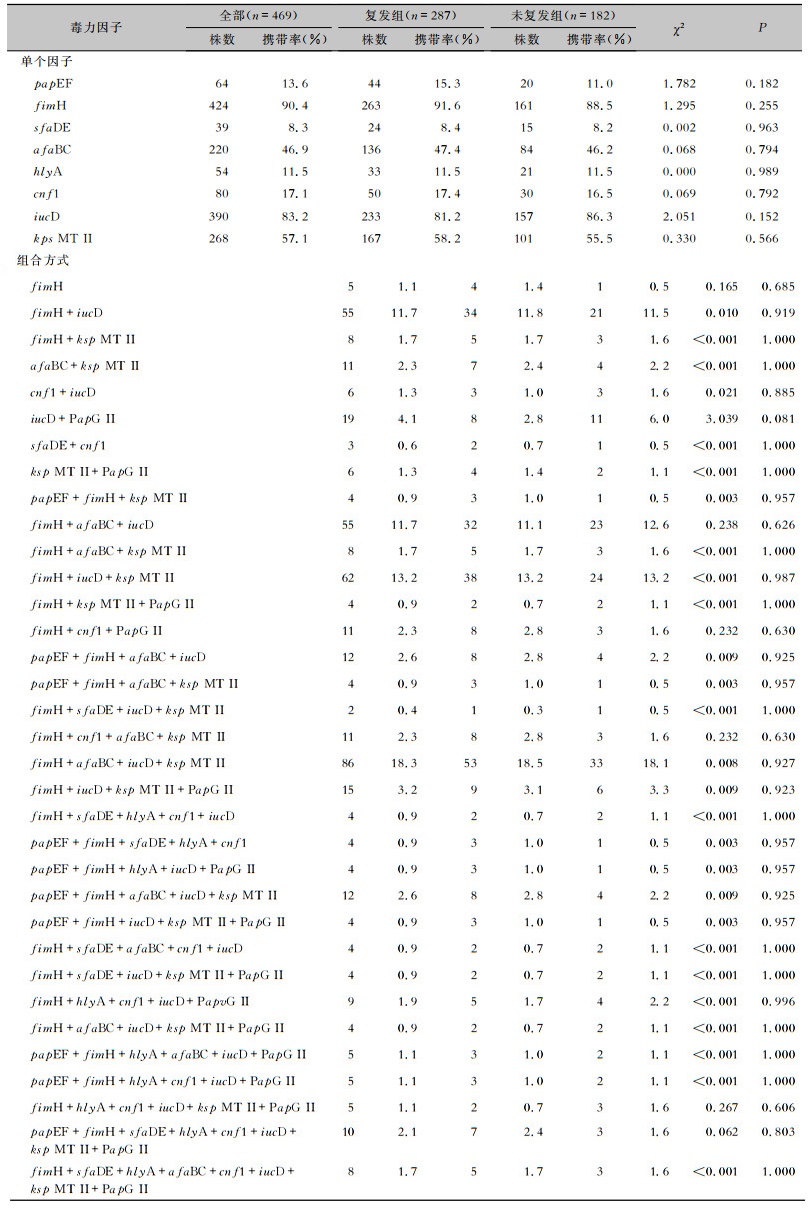

检测469株ESBLs-UPEC 9种毒力因子携带情况,结果显示,90.4%的菌株携带毒力因子fimH,83.2%的菌株携带毒力因子iucD,毒力因子sfaDE检出率最低,为8.3%。毒力因子最常见的组合式为fimH+afaBC+iucD+ksp MT Ⅱ(18.3%),其次为fimH+iucD+ksp MT Ⅱ(13.2%)。毒力因子PCR扩增产物电泳结果见图 1。毒力因子的组合方式与复发之间缺乏明确相关性,复发组与未复发组ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子组合方式比较,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),见表 3。

|

| 注:M为DNA Marker,1~5泳道为检测标本;A为毒力因子fimH,B为毒力因子papEF,C为毒力因子hlyA,D为毒力因子sfaDE,E为毒力因子afaBC,F为毒力因子cnf1,G为毒力因子iucD,H为毒力因子kps MT Ⅱ,I为毒力因子papG Ⅱ。 图 1 ESBLs-UPEC菌株毒力因子PCR扩增产物电泳图 Figure 1 Electrophoresis map of PCR amplified product of virulence factors in ESBLs-UPEC strains |

| 表 3 ESBLs-UPEC菌株携带的毒力因子分布情况 Table 3 Distribution of virulence factors in ESBLs-UPEC strains |

|

469例随访患者根据菌株携带的毒力因子数量分为七组,对每组毒力因子数量与复发率(一种:80.0%;两种:58.3%;三种:61.1%;四种:63.1%;五种:61.2%;六种:53.3%;八种:66.7%)进行Pearson相关性检验分析,结果表明,毒力因子的数量与复发之间无明显相关性(r=-0.382 1,P=0.397 7)。

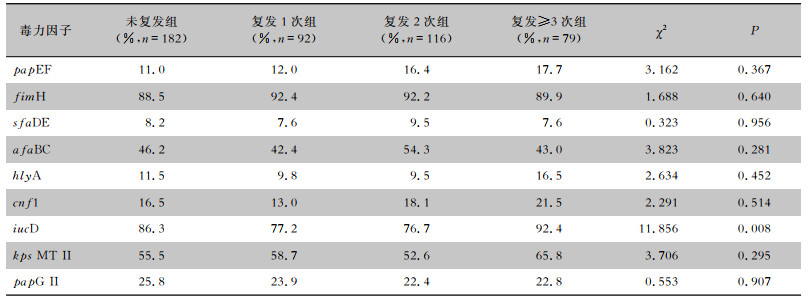

2.5 复发次数与毒力因子差异的分析根据6个月内ESBLs-UPEC尿路感染复发的次数,将患者分为未复发组(n=182)、复发1次组(n=92)、复发2次组(n=116)和复发≥3次组(n=79),比较不同复发次数患者尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC携带9种毒力因子的差异。结果显示,不同复发次数患者尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子iucD的携带率差异具有统计学意义(P=0.008),复发≥3次的患者尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子iucD的携带率(92.4%)高于未复发组(86.3%)、复发1次组(77.2%)和复发2次组(76.7%),其余尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子携带率比较,差异均无统计学(均P>0.05)。见表 4。

| 表 4 6个月内不同复发次数患者尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子携带情况 Table 4 Carriage of virulence factors in ESBLs-UPEC from patients with different recurrence of URI within 6 months |

|

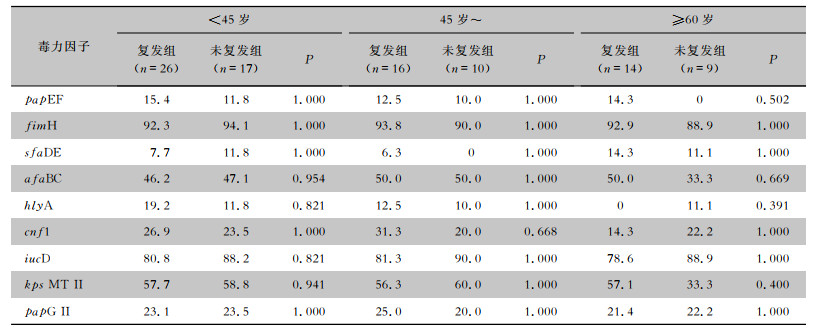

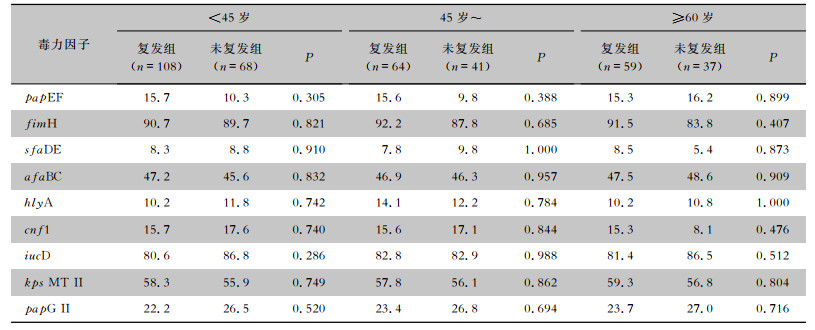

根据年龄将患者分为<45岁组、45岁~组和≥60岁组,分析男性/女性相同年龄阶段的复发组和未复发组患者尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC的毒力因子携带率的差异,结果显示,9种毒力因子复发组与未复发组比较,差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。见表 5、6。

| 表 5 不同年龄阶段男性患者复发组和未复发组尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子的携带情况比较 Table 5 Comparison of carriage of virulence factors in ESBLs-UPEC from UTI male patients of different age groups in the recurrence and non-recurrence groups |

|

| 表 6 不同年龄阶段女性患者复发组和未复发组尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子的携带情况比较 Table 6 Comparison of carriage of virulence factors in ESBLs-UPEC from UTI female patients of different age groups in the recurrence and non-recurrence groups |

|

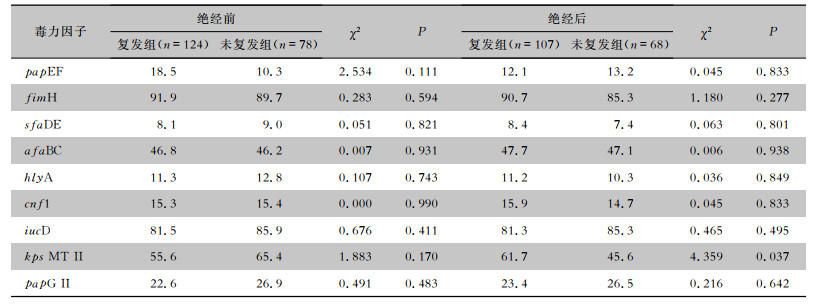

根据绝经与否,将377例女性患者分为绝经前组(n=202)和绝经后组(n=175),对比相同雌激素水平下复发组和未复发组患者尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子的差异。结果显示,绝经前女性患者,复发组和未复发组尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC 9种毒力因子携带率比较,差异均无统计学差异意义(均P>0.05);绝经后女性患者,复发组和未复发组尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子kps MT Ⅱ携带率比较,复发组尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子kps MT Ⅱ携带率高于未复发组(61.7% VS 45.6%,P=0.037),差异有统计学意义,其余毒力因子携带率两组比较,差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。见表 7。

| 表 7 绝经前后复发组和未复发组患者尿路感染ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子携带率(%) Table 7 Carriage rate of virulence factors in ESBLs-UPEC from UTI patients before and after menopause in the recurrence and non-recurrence groups (%) |

|

复发性尿路感染是目前世界范围内一个重大的健康、经济和生活质量负担,除了已知的既往感染史和宿主易感性是尿路感染复发的重大风险因素之外[8, 11-13],在临床工作中往往缺乏相关的检测指标评估尿路感染复发的风险。既往研究探索了临床症状、ST131分离株、肠道定植和膀胱印记等与尿路感染复发的相关性[6-9],而对于ESBLs-UPEC携带的毒力因子与尿路感染复发关系的研究尚少,因此进行了本研究。

ESBLs-UPEC往往表现为多重耐药,可导致反复、难治性尿路感染,不仅给临床治疗带来困难,也增加了患者的经济负担[14]。因此,了解ESBLs-UPEC的耐药性特点,可为临床合理使用抗菌药物,减少多重耐药菌株的产生提供依据。本研究结果显示,ESBLs-UPEC对哌拉西林/他唑巴坦(9.4%)、头孢哌酮/舒巴坦(6.2%)和阿莫西林/克拉维酸(14.3%)等β-内酰胺酶抑制剂、碳青霉烯类、替加环素(0)和阿米卡星(4.5%)的耐药率均较低,该结果与国内其他地区的研究[8]结果相仿,但与国外研究[15-16]结果不同,耐药情况的多样性可能与地区、医院规模、疾病类型及医院用药习惯等有关。此外,本研究比较了复发组患者在尿路感染复发前后ESBLs-UPEC菌株耐药情况的变化,结果显示,复发前后ESBLs-UPEC对药物的敏感率差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),表明ESBLs-UPEC引起的rUTI与抗菌药物敏感大肠埃希菌引起的rUTI相似[17-18],即大多数复发是由同源菌株引起的,尤其是前6个月内发生的复发很可能是由同一感染菌株引起[19]。因此,在治疗本地区ESBLs-UPEC导致的复发性尿路感染时,上述耐药率较低抗菌药物可作为经验选择药物。但应特别注意,已出现少量对美罗培南、亚胺培南和替加环素耐药的尿源性大肠埃希菌(UPEC)菌株,可能与此类药物在临床中的使用频率增高有关。

ESBLs-UPEC菌株往往携带多种毒力因子,包括1型菌毛黏附因子(type 1 fimbrial adhesins)、P菌毛黏附因子(P-fimbrial adhesins)、无菌毛黏附因子(afimbrial adhesins)和S-菌毛黏附因子(S-fimbrial adhesins),以及铁摄取蛋白(siderophore)、荚膜(capsule)、溶血和细胞毒坏死因子(hemolytic and cytotoxic necrotizing factors)等,这些毒力因子通过促进细菌的黏附、定植和传播,增强细菌在泌尿道的适应性,从而在宿主易感性增加时引起尿路感染[20-21],而毒力因子是否和尿路感染复发相关目前尚不清楚。本研究结果显示,所有被检测的菌株均至少携带有9种检测的毒力因子中的一种,其中最常见的毒力因子为fimH(90.4%)。fimH负责编码1型菌毛,通过诱导肌动蛋白重排导致细菌侵入,有助于细胞内细菌群落的形成,对其定植、侵袭和持留有重要作用[22-24]。其次是毒力因子iucD(83.2%),毒力因子iucD编码一种铁摄入蛋白,使细菌能够摄取尿液中的铁离子,有助于细菌在膀胱定植,在细胞内细菌群落增殖中起着关键作用[25-26],具有高度黏附力和铁摄取能力的UPEC菌株可能通过形成病原菌储存库进一步导致rUTI持续存在[27]。其余毒力因子在细菌感染过程中也发挥了不同的作用,papEF有助于细菌黏附于黏膜上皮和组织基质,诱导细胞因子产生[28-29]。sfaDE、afaBC和papG Ⅱ黏附于黏膜上皮和组织基质[30-35]。hlyA具有溶血和细胞毒性作用[36-37]。cnf1干扰吞噬作用和细胞凋亡[38-39]。kps MT Ⅱ编码保护/入侵蛋白,参与细菌生物膜的形成[40-41]。同时ESBLs-UPEC菌株携带的毒力因子组合方式也是大不相同,统计毒力因子组合方式发现,最常见的为fimH+afaBC+iucD+ksp MT Ⅱ(18.3%),其次为fimH+iucD+ksp MT Ⅱ(13.2%)。

由于rUTI是指6个月内发生2次及以上,或1年内发生3次以上的尿路感染,且25%~40%的患者在初次感染后6个月内会再次感染[24]。为了进一步了解毒力因子与尿路感染复发之间的关系,本研究在患者接受抗菌药物治疗且至少有1次清洁中段尿培养阴性或尿常规检测白细胞数正常后,对其进行为期6个月的随访,追踪患者是否再次出现尿频、尿急、尿痛等症状,并定期复查尿常规、尿培养和细菌药敏试验。本研究最终对469例患者完成了6个月的随访。根据随访结果,对尿路感染是否复发进行了分组及统计分析,结果显示,不同的毒力因子数量和组合方式与复发之间无明显的相关性(P>0.05)。而6个月内复发≥3次组的患者ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子iucD的携带率高于其他组(P=0.008),可能是由于携带毒力因子iucD的ESBLs-UPEC拥有更强的铁摄取能力,能够摄取尿液中的铁离子,从而增加了在泌尿道的适应性,能长期存在于泌尿道环境中[25-27],引起UTI的反复发作。对于相同性别和年龄阶段的患者,复发组与未复发组ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子携带率比较,差异无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。而对于绝经后的女性,复发组ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子kps MT Ⅱ携带率高于未复发组(P=0.037),其他毒力因子携带率两组比较,差异无统计学(均P>0.05)。绝经后的妇女由于雌激素水平较低会导致阴道萎缩,泌尿生殖道上皮细胞和泌尿生殖道微生物群发生变化(主要是乳酸杆菌的丧失和阴道pH值的增加),导致泌尿道病原体在阴道定植引起更频繁的UTI[42-44]。而毒力因子kps MT Ⅱ作为一种保护/入侵编码基因,与细菌生物膜的形成有关[40-41],可能是绝经后阴道抵御细菌的能力下降,导致携带kps MT Ⅱ的ESBLs-UPEC有更多的尿路感染复发概率。

综上所述,对于该地区ESBLs-UPEC引起的尿路感染患者,建议使用碳青霉烯类、氨基糖苷类和β-内酰胺酶抑制剂复合剂作为临床经验用药,不建议使用头孢菌素类、磺胺类、单酰胺类和喹诺酮类药物进行治疗。ESBLs-UPEC常见毒力因子中fimH和iucD的携带率较高,且毒力因子iucD更常见于多次复发的尿路感染的ESBLs-UPEC。而绝经后的女性复发患者中ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子kps MT Ⅱ携带率高于未复患者。本研究虽检测了ESBLs-UPEC毒力因子的携带情况,但未对其表达情况进行深入探讨,存在一定的局限性,而目前国内外缺乏相似的研究报道,本研究团队计划在之后进行更深入的研究,以期为疫苗的研发提供新的靶点,为rUTI的治疗与预防提供新的研究方向。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Zhang H, Johnson A, Zhang G, et al. Susceptibilities of Gram-negative bacilli from hospital-and community-acquired intra-abdominal and urinary tract infections: a 2016-2017 update of the Chinese SMART study[J]. Infect Drug Resist, 2019, 12: 905-914. DOI:10.2147/IDR.S203572 |

| [2] |

Ronald A. The etiology of urinary tract infection: traditional and emerging pathogens[J]. Dis Mon, 2003, 49(2): 71-82. DOI:10.1067/mda.2003.8 |

| [3] |

Sun JD, Du L, Yan L, et al. Eight-year surveillance of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in southwest China[J]. Infect Drug Resist, 2020, 13: 1197-1202. DOI:10.2147/IDR.S250775 |

| [4] |

Shakya P, Shrestha D, Maharjan E, et al. ESBL production among E. coli and Klebsiella spp. causing urinary tract infection: a hospital based study[J]. Open Microbiol J, 2017, 11: 23-30. DOI:10.2174/1874285801711010023 |

| [5] |

Bauckman KA, Mysorekar IU. Ferritinophagy drives uropathogenic Escherichia coli persistence in bladder epithelial cells[J]. Autophagy, 2016, 12(5): 850-863. DOI:10.1080/15548627.2016.1160176 |

| [6] |

Ismail MD, Ali I, Hatt S, et al. Association of Escherichia coli ST131 lineage with risk of urinary tract infection recurrence among young women[J]. J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 2018, 13: 81-84. DOI:10.1016/j.jgar.2017.12.006 |

| [7] |

O'Brien VP, Hannan TJ, Yu L, et al. A mucosal imprint left by prior Escherichia coli bladder infection sensitizes to recurrent disease[J]. Nat Microbiol, 2016, 2: 16196. DOI:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.196 |

| [8] |

Guglietta A. Recurrent urinary tract infections in women: risk factors, etiology, pathogenesis and prophylaxis[J]. Future Microbiol, 2017, 12: 239-246. DOI:10.2217/fmb-2016-0145 |

| [9] |

Gopal M, Northington G, Arya L. Clinical symptoms predictive of recurrent urinary tract infections[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2007, 197(1): 74. |

| [10] |

Bouchillon SK, Badal RE, Hoban DJ, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of inpatient urinary tract isolates of Gram-negative bacilli in the United States: results from the study for monitoring antimicrobial resistance trends (SMART) program: 2009-2011[J]. Clin Ther, 2013, 35(6): 872-877. DOI:10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.03.022 |

| [11] |

Ali I, Rafaque Z, Ahmed I, et al. Phylogeny, sequence-ty-ping and virulence profile of uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) strains from Pakistan[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2019, 19(1): 620. DOI:10.1186/s12879-019-4258-y |

| [12] |

Takahashi A, Kanamaru S, Kurazono H, et al. Escherichia coli isolates associated with uncomplicated and complicated cystitis and asymptomatic bacteriuria possess similar phylogenies, virulence genes, and O-serogroup profiles[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2006, 44(12): 4589-4592. DOI:10.1128/JCM.02070-06 |

| [13] |

Rezatofighi SE, Mirzarazi M, Salehi M. Virulence genes and phylogenetic groups of uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from patients with urinary tract infection and uninfected control subjects: a case-control study[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2021, 21(1): 361. DOI:10.1186/s12879-021-06036-4 |

| [14] |

Lee DS, Lee SJ, Choe HS. Community-acquired urinary tract infection by Escherichia coli in the era of antibiotic resistance[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2018, 2018: 7656752. |

| [15] |

Veeraraghavan B, Jesudason MR, Prakasah JAJ, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of Gram-negative bacteria causing infections collected across India during 2014-2016:study for monitoring antimicrobial resistance trend report[J]. Indian J Med Microbiol, 2018, 36(1): 32-36. DOI:10.4103/ijmm.IJMM_17_415 |

| [16] |

van Driel AA, Notermans DW, Meima A, et al. Antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli isolated from uncomplicated UTI in general practice patients over a 10-year period[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2019, 38(11): 2151-2158. DOI:10.1007/s10096-019-03655-3 |

| [17] |

Ejrnaes K, Sandvang D, Lundgren B, et al. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of Escherichia coli strains from samples collected before and after pivmecillinam or placebo treatment of uncomplicated community-acquired urinary tract infection in women[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2006, 44(5): 1776-1781. DOI:10.1128/JCM.44.5.1776-1781.2006 |

| [18] |

Kõljalg S, Truusalu K, Vainumäe I, et al. Persistence of Escherichia coli clones and phenotypic and genotypic antibiotic resistance in recurrent urinary tract infections in childhood[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2009, 47(1): 99-105. DOI:10.1128/JCM.01419-08 |

| [19] |

Karami N, Lindblom A, Yazdanshenas S, et al. Recurrence of urinary tract infections with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli caused by homologous strains among which clone ST131-O25b is dominant[J]. J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 2020, 22: 126-132. DOI:10.1016/j.jgar.2020.01.024 |

| [20] |

Mokady D, Gophna U, Ron EZ. Virulence factors of septicemic Escherichia coli strains[J]. Int J Med Microbiol, 2005, 295(6/7): 455-462. |

| [21] |

Jauréguy F, Carbonnelle E, Bonacorsi S, et al. Host and bacterial determinants of initial severity and outcome of Escherichia coli sepsis[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2007, 13(9): 854-862. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01775.x |

| [22] |

Malekzadegan Y, Khashei R, Sedigh Ebrahim-Saraie H, et al. Distribution of virulence genes and their association with antimicrobial resistance among uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from Iranian patients[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2018, 18(1): 572. DOI:10.1186/s12879-018-3467-0 |

| [23] |

Sheldon IM, Rycroft AN, Dogan B, et al. Specific strains of Escherichia coli are pathogenic for the endometrium of cattle and cause pelvic inflammatory disease in cattle and mice[J]. PLoS One, 2010, 5(2): e9192. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0009192 |

| [24] |

O'Brien VP, Hannan TJ, Nielsen HV, et al. Drug and vaccine development for the treatment and prevention of urinary tract infections[J]. Microbiol Spectr, 2016, 4(1): 4. |

| [25] |

Tiba MR, Yano T, Leite Dda S. Genotypic characterization of virulence factors in Escherichia coli strains from patients with cystitis[J]. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo, 2008, 50(5): 255-260. DOI:10.1590/S0036-46652008000500001 |

| [26] |

Le Gall T, Clermont O, Gouriou S, et al. Extraintestinal virulence is a coincidental by-product of commensalism in B2 phylogenetic group Escherichia coli strains[J]. Mol Biol Evol, 2007, 24(11): 2373-2384. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msm172 |

| [27] |

Hedlund M, Wachtler C, Johansson E, et al. P fimbriae-dependent, lipopolysaccharide-independent activation of epithe-lial cytokine responses[J]. Mol Microbiol, 1999, 33(4): 693-703. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01513.x |

| [28] |

Godaly G, Bergsten G, Frendéus B, et al. Innate defences and resistance to Gram-negative mucosal infection[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2000, 485: 9-24. |

| [29] |

Schembri MA, Klemm P. Biofilm formation in a hydrodynamic environment by novel fimh variants and ramifications for virulence[J]. Infect Immun, 2001, 69(3): 1322-1328. DOI:10.1128/IAI.69.3.1322-1328.2001 |

| [30] |

Westerlund B, Korhonen TK. Bacterial proteins binding to the mammalian extracellular matrix[J]. Mol Microbiol, 1993, 9(4): 687-694. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01729.x |

| [31] |

Marre R, Kreft B, Hacker J. Genetically engineered S and F1C fimbriae differ in their contribution to adherence of Escherichia coli to cultured renal tubular cells[J]. Infect Immun, 1990, 58(10): 3434-3437. DOI:10.1128/iai.58.10.3434-3437.1990 |

| [32] |

Mainil J. Escherichia coli virulence factors[J]. Vet Immunol Immunopathol, 2013, 152(1-2): 2-12. DOI:10.1016/j.vetimm.2012.09.032 |

| [33] |

Nowicki B, Labigne A, Moseley S, et al. The Dr hemagglutinin, afimbrial adhesins AFA-Ⅰ and AFA-Ⅲ, and F1845 fimbriae of uropathogenic and diarrhea-associated Escherichia coli belong to a family of hemagglutinins with Dr receptor recognition[J]. Infect Immun, 1990, 58(1): 279-281. DOI:10.1128/iai.58.1.279-281.1990 |

| [34] |

Welch RA. Pore-forming cytolysins of Gram-negative bacteria[J]. Mol Microbiol, 1991, 5(3): 521-528. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00723.x |

| [35] |

Eberspächer B, Hugo F, Bhakdi S. Quantitative study of the binding and hemolytic efficiency of Escherichia coli hemolysin[J]. Infect Immun, 1989, 57(3): 983-988. DOI:10.1128/iai.57.3.983-988.1989 |

| [36] |

Caprioli A, Falbo V, Ruggeri FM, et al. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor production by hemolytic strains of Escherichia coli causing extraintestinal infections[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 1987, 25(1): 146-149. DOI:10.1128/jcm.25.1.146-149.1987 |

| [37] |

Fiorentini C, Fabbri A, Matarrese P, et al. Hinderance of apo-ptosis and phagocytic behaviour induced by Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1:two related activities in epithe-lial cells[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1997, 241(2): 341-346. DOI:10.1006/bbrc.1997.7723 |

| [38] |

Baldiris-Avila R, Montes-Robledo A, Buelvas-Montes Y. Phylogenetic classification, biofilm-forming capacity, virulence factors, and antimicrobial resistance in uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC)[J]. Curr Microbiol, 2020, 77(11): 3361-3370. DOI:10.1007/s00284-020-02173-2 |

| [39] |

Naves P, del Prado G, Huelves L, et al. Correlation between virulence factors and in vitro biofilm formation by Escherichia coli strains[J]. Microb Pathog, 2008, 45(2): 86-91. DOI:10.1016/j.micpath.2008.03.003 |

| [40] |

Legros N, Ptascheck S, Pohlentz G, et al. PapG subtype-specific binding characteristics of Escherichia coli towards globo-series glycosphingolipids of human kidney and bladder uroepithelial cells[J]. Glycobiology, 2019, 29(11): 789-802. DOI:10.1093/glycob/cwz059 |

| [41] |

Tseng CC, Huang JJ, Wang MC, et al. PapG Ⅱ adhesin in the establishment and persistence of Escherichia coli infection in mouse kidneys[J]. Kidney Int, 2007, 71(8): 764-770. DOI:10.1038/sj.ki.5002111 |

| [42] |

Jung C, Brubaker L. The etiology and management of recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women[J]. Climacteric, 2019, 22(3): 242-249. DOI:10.1080/13697137.2018.1551871 |

| [43] |

Calleja-Agius J, Brincat MP. The urogenital system and the menopause[J]. Climacteric, 2015, 18(Suppl 1): 18-22. |

| [44] |

Ferrante KL, Wasenda EJ, Jung CE, et al. Vaginal estrogen for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in postme-nopausal women: a randomized clinical trial[J]. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg, 2021, 27(2): 112-117. DOI:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000749 |