2. 广西壮族自治区妇幼保健院新生儿外科, 广西 南宁 530003

2. Department of Neonatal Surgery, Maternal and Child Health Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Nanning 530003, China

新生儿肠造瘘术是新生儿外科常见的手术之一,常用于新生儿坏死性小肠结肠炎(necrotizing enterocolitis, NEC)、巨结肠、肠闭锁、回肠结肠坏死并穿孔、肠梗阻等危重患者,其具有手术时间短、创伤小、效果显著等优点[1]。肠造瘘通过暂时性的粪便改流方式,能尽早恢复肠道功能和血液供应,有效挽救新生儿生命[2-3]。但是由于新生儿免疫系统发育尚未完善,住院新生儿病情变化快、并发症多、侵入性操作频繁,一直被认为是医院感染的高危人群[4]。因此,手术后如何预防医院感染的发生对新生儿以及医护人员都是一种严峻的考验。本研究回顾性收集行肠造瘘术新生儿的病历资料,分析其临床特征、手术信息及医院感染特点,为临床预防及控制新生儿肠造瘘术后医院感染提供参考依据。

1 对象与方法 1.1 研究对象某院2019年6月—2022年6月新生儿外科病房收治的新生儿期(足月儿出生28 d内,早产儿矫正胎龄44周内)行肠造瘘术的新生儿。排除标准:①非新生儿时期造瘘者;②造瘘术后病情严重、死亡或家属签字放弃治疗自动出院者;③合并有21三体综合征等遗传代谢性疾病者;④资料不完整或失访者。

1.2 研究方法回顾性收集新生儿的病历资料,包括基本资料、临床资料、手术情况、医院感染发生情况。将纳入研究的新生儿按照是否发生医院感染分为医院感染组和非医院感染组。手术部位感染随访至新生儿手术后一个月。

1.3 医院感染诊断标准参照卫生部2001年颁发的《医院感染诊断标准(试行)》(卫医发[2001]2号)[5]执行,新生儿肠造瘘术后新发的医院感染均纳入研究。

1.4 统计学方法数据处理应用SPSS 25.0软件,符合正态分布的计量资料以均数±标准差表示,采用t检验进行比较;计数资料以例数表示,采用χ2检验和Fisher确切概率法进行比较;多因素分析采用二元logistic回归分析。以P≤0.05为差异有统计学意义。

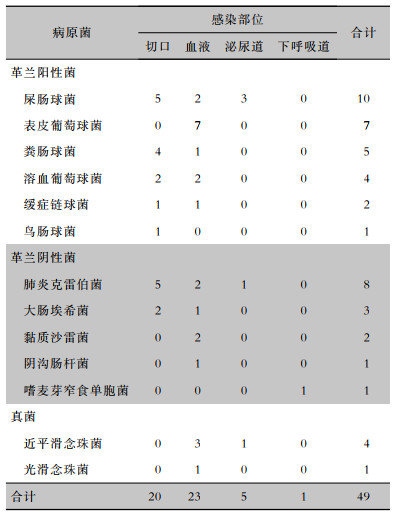

2 结果 2.1 基本资料共收集行肠造瘘术新生儿272例,其中非新生儿时期行造瘘术者30例,家属签字放弃治疗8例,合并遗传代谢性疾病6例,死亡1例,最终纳入病例227例。其中男性145例,女性82例;顺产118例,剖宫产109例;40例为双胎妊娠,其余187例为单胎妊娠;平均出生胎龄为(34.03±4.62)周;平均出生体重为(2 207.63±934.57)g。发生医院感染71例,84例次,本研究术后医院感染均在住院期间发生。医院感染发病率为31.28%,例次发病率为37.00%,其中切口感染24例次,胃肠道感染24例次,血流感染23例次,泌尿道感染6例次,下呼吸道感染6例次,中枢神经系统感染1例次。检出病原菌49株,包括屎肠球菌10株,肺炎克雷伯菌8株,表皮葡萄球菌7株,粪肠球菌5株,近平滑念珠菌4株,溶血葡萄球菌4株,其他病原菌11株。革兰阳性菌占59.18%。见表 1。

| 表 1 肠造瘘术后医院感染新生儿检出病原菌的分布情况(株) Table 1 Distribution of pathogenic bacteria isolated from neonates with HAI after enterostomy (No. of isolates) |

|

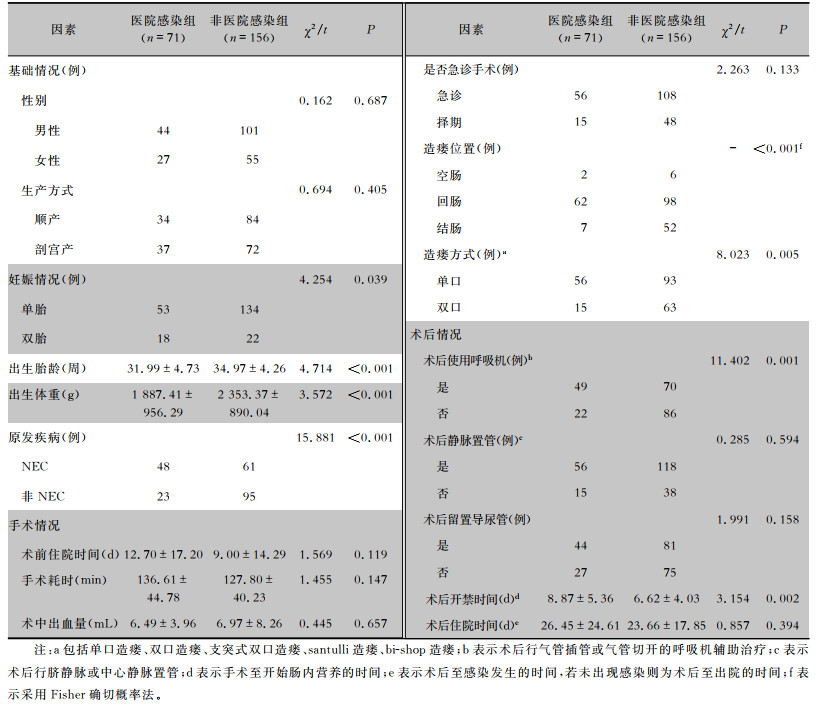

227例新生儿的原发疾病分别为新生儿NEC 109例,肛门闭锁42例,肠闭锁23例,肠梗阻20例,肠穿孔18例,巨结肠7例,急性腹膜炎6例,肠狭窄2例。将其按照手术后是否发生医院感染分为医院感染组(71例)和非医院感染组(156例)。单因素分析结果显示,两组妊娠情况、出生胎龄、出生体重、原发疾病、造瘘位置、造瘘方式、术后使用呼吸机、术后开禁时间比较,差异均有统计学意义(均P<0.05)。见表 2。

| 表 2 肠造瘘术新生儿手术后医院感染的单因素分析 Table 2 Univariate analysis on postoperative HAI in neonates underwent enterostomy |

|

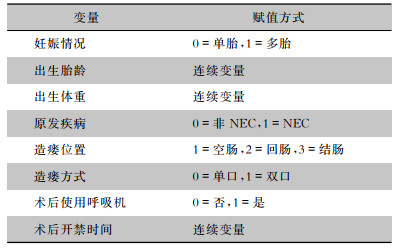

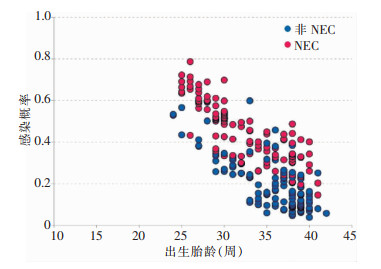

以是否发生医院感染为因变量,将单因素分析有统计学差异的指标进行二元logistic多因素回归分析,结果显示出生胎龄小[OR=0.806, 95%CI(0.676~0.962)]和原发疾病为NEC[OR=0.484, 95%CI(0.247~0.948)] 是新生儿肠造瘘术后医院感染的独立危险因素(P<0.05),见表 3、4。将回归方程模型拟合的术后医院感染概率和独立危险因素(出生胎龄和原发疾病)绘制成散点图可得到出生胎龄越大,医院感染的发生概率越低。在相同出生胎龄的情况下,NEC比非NEC新生儿发生医院感染的概率高,见图 1。

| 表 3 二元logistic回归法变量赋值情况 Table 3 Variable assignment in binary logistic regression |

|

| 表 4 肠造瘘术新生儿手术后医院感染的多因素分析 Table 4 Multivariate logistic regression analysis on postope-rative HAI in neonates underwent enterostomy |

|

|

| 图 1 logistic回归模型拟合的肠造瘘术新生儿手术后医院感染独立危险因素概率估计 Figure 1 Probability estimation of independent risk factors for postoperative HAI in neonates with enterostomy fitted by logistic regression model |

新生儿科是医院感染预防与控制的重点科室,手术新生儿更是医院感染管理人员重点关注的对象。手术后感染不仅延长患者住院时间、影响手术效果及患者的预后,严重者可导致全身性感染,甚至可能导致患者死亡[6]。本研究发现新生儿肠造瘘术后医院感染发病率为31.28%,医院感染例次率为37.00%。其中主要为切口感染、胃肠道感染和血流感染。在欧洲,手术部位感染在常见医院感染类型中居第二位,会延长患者的住院时间,增加医疗费用[7]。本研究中切口感染和胃肠道感染均为24例次,例次感染率均为10.57%,切口感染率与国外学者的研究结果(4.3%~14.9%)较接近[8-9],略高于国内学者的研究[10-12]。医院感染病原菌主要为革兰阳性菌,占全部检出菌的59.18%,包括肠球菌、葡萄球菌和链球菌。上述菌群大多为人类皮肤和肠道的定植菌,在机体免疫力下降时可成为条件致病菌,造成机体的感染和损伤,与其他文献[13]报道的新生儿外科感染性疾病检出病原菌多为金黄色葡萄球菌稍有不同,但在伤口分泌物的培养中,肺炎克雷伯菌占检出菌首位(25.00%,5/20),与其他学者的研究[11]结果接近。

影响肠造瘘术后医院感染的因素很多,目前的研究[14-15]显示,在造口相关并发症(包括造口裂开或感染、脱垂、肠梗阻等)方面,NEC新生儿比非NEC新生儿(包括肠畸形、肠穿孔、肠梗阻、肠闭锁等)的发病风险高。彭艳芬等[16]的研究表明空肠、回肠闭锁新生儿比NEC新生儿术后营养不良风险高。为了解不同原发疾病对于医院感染发生的差异,本研究进行了logistic多因素回归分析,结果显示NEC是肠造瘘术新生儿手术后发生医院感染的独立危险因素。这可能与NEC新生儿本身病情凶险、高发病率、高病死率[17-19],以及术后易出现肠液的大量丢失,营养物质吸收率低,水、电解质的失衡等有关[20-21]。美国外科医师学会一项对外科手术质量改进计划的回顾性研究得出,出生胎龄<30周的早产儿是肠造瘘术后并发症(败血症、尿路感染、手术切口裂开等)的独立危险因素[22],其他研究[23]也证实了这一点。本研究经过logistic多因素分析显示,新生儿出生胎龄小是手术后医院感染发生的危险因素。尽管部分早产儿手术时已校正了胎龄和体重,达到正常新生儿的水平,但是出生低胎龄仍然是一项危险因素。胎龄小的新生儿由于器官发育尚未成熟,免疫力较弱,体温调控能力弱,再加上手术后可能要接受气管插管、中心静脉置管、脐静脉置管等侵入性操作,可能使新生儿肺部受到正压通气的损伤、毛细血管脆弱出血等,这些可能对手术后医院感染的发生产生潜在的影响。

综上所述,NEC和出生低胎龄是肠造瘘新生儿手术后医院感染发生的危险因素,临床应针对此类新生儿加以关注,制定并落实相应的防控措施,以减少医院感染的发生。由于数据收集的时限仅3年,且仅来自于一所医院,代表性可能有所欠缺。对于肠造瘘术后医院感染高发部位的研究可进行进一步分析,从而更好的为临床服务。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Martynov I, Raedecke J, Klima-Frysch J, et al. The outcome of Bishop-Koop procedure compared to divided stoma in neonates with meconium ileus, congenital intestinal atresia and necrotizing enterocolitis[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2019, 98(27): e16304. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000016304 |

| [2] |

方琼, 张苇, 朱莹. 造口综合护理对新生儿肠造瘘在减少术后并发症中应用效果[J]. 实用临床医药杂志, 2018, 22(6): 107-110. Fang Q, Zhang W, Zhu Y. Effect of comprehensive nursing on reducing postoperative complications of neonatal enterostomy[J]. Journal of Clinical Medicine in Practice, 2018, 22(6): 107-110. |

| [3] |

唐云跃, 岳树锦, 郭彤, 等. 国外最佳肠造口临床实践指南健康教育推荐意见的分析研究[J]. 护理研究, 2020, 34(10): 1733-1738. Tang YY, Yue SJ, Guo T, et al. Analysis on health education recommendation of best clinical practice guidelines of enterostomy abroad[J]. Chinese Nursing Research, 2020, 34(10): 1733-1738. DOI:10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2020.10.010 |

| [4] |

Sharma D, Shastri S. Lactoferrin and neonatology-role in neonatal sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis: present, past and future[J]. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med, 2016, 29(5): 763-770. DOI:10.3109/14767058.2015.1017463 |

| [5] |

中华人民共和国卫生部. 医院感染诊断标准(试行)[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2001, 81(5): 314-320. Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. Diagnostic criteria for nosocomial infections(proposed)[J]. Natio-nal Medical Journal of China, 2001, 81(5): 314-320. |

| [6] |

李刚, 李振军, 王奇, 等. 回肠造口术后并发伤口感染病原菌及影响因素[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2022, 32(1): 85-88. Li G, Li ZJ, Wang Q, et al. Distribution of pathogens isolated from ileostomy patients complicated with postoperative wound infection and influencing factors[J]. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology, 2022, 32(1): 85-88. |

| [7] |

World Health Organization. Global guidelines on the prevention of surgical site infection[EB/OL].[2017-08-27]. http://www.who.int/gpsc/ssi-prevetion-guidelines/en/.

|

| [8] |

Ban KA, Minei JP, Laronga C, et al. American college of surgeons and surgical infection society: surgical site infection guidelines, 2016 update[J]. J Am Coll Surg, 2017, 224(1): 59-74. DOI:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.10.029 |

| [9] |

Woldemicael AY, Bradley S, Pardy C, et al. Surgical site infection in a tertiary neonatal surgery centre[J]. Eur J Pediatr Surg, 2019, 29(3): 260-265. DOI:10.1055/s-0038-1636916 |

| [10] |

中华人民共和国中央人民政府. 关于外科手术部位感染预防控制指南(试行)通知[EB/OL]. (2010-12-14)[2022-10-10]. http://www.gov.cn/govweb/gzdt/2010-12/14/content_1765450.htm. The Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China. Notice on prevention and control guidelines for infection at surgical sites (trial)[EB/OL]. (2010-12-14)[2022-10-10]. http://www.gov.cn/govweb/gzdt/2010-12/14/content_1765450.htm. |

| [11] |

严文波, 王俊, 潘伟华, 等. 单中心新生儿外科手术部位感染危险因素分析[J]. 中华小儿外科杂志, 2020, 41(11): 1027-1030. Yan WB, Wang J, Pan WH, et al. Risk factors analysis of neonatal surgical site infection: single center experience[J]. Chinese Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 2020, 41(11): 1027-1030. |

| [12] |

姚海平, 杨敏, 王献良, 等. 先天性巨结肠患儿根治术后并发小肠结肠炎的影响因素分析[J]. 中华现代护理杂志, 2022, 28(15): 2083-2086. Yao HP, Yang M, Wang XL, et al. Influencing factors of enterocolitis after radical operation in children with Hirschsprung's disease[J]. Chinese Journal of Modern Nursing, 2022, 28(15): 2083-2086. |

| [13] |

陈凤萍, 李孟, 李正峰. 新生儿外科感染性疾病病原菌分布与耐药性[J]. 中国消毒学杂志, 2017, 34(8): 771-773. Chen FP, Li M, Li ZF. Pathogens distribution and drug resistance of neonatal surgical patients infections[J]. Chinese Journal of Disinfection, 2017, 34(8): 771-773. |

| [14] |

Chong C, van Druten J, Briars G, et al. Neonates living with enterostomy following necrotising enterocolitis are at high risk of becoming severely underweight[J]. Eur J Pediatr, 2019, 178(12): 1875-1881. |

| [15] |

Wolf L, Gfroerer S, Fiegel H, et al. Complications of newborn enterostomies[J]. World J Clin Cases, 2018, 6(16): 1101-1110. |

| [16] |

彭艳芬, 何秋明, 郑海清, 等. 新生儿小肠造瘘术后营养状态及危险因素分析[J]. 中华新生儿科杂志(中英文), 2018, 33(5): 350-353. Peng YF, He QM, Zheng HQ, et al. Nutritional outcomes and risk factors of neonatal enterostomy[J]. Chinese Journal of Neonatology, 2018, 33(5): 350-353. |

| [17] |

Jiang SY, Yan WL, Li SJ, et al. Mortality and morbidity in infants <34 weeks' gestation in 25 NICUs in China: a prospective cohort study[J]. Front Pediatr, 2020, 8: 33. |

| [18] |

Eaton S, Rees CM, Hall NJ. Current research on the epidemio-logy, pathogenesis, and management of necrotizing enteroco-litis[J]. Neonatology, 2017, 111(4): 423-430. |

| [19] |

Jones IH, Hall NJ. Contemporary outcomes for infants with necrotizing enterocolitis-a systematic review[J]. J Pediatr, 2020, 220: 86-92. |

| [20] |

中华医学会小儿外科学分会新生儿学组. 新生儿坏死性小肠结肠炎小肠造瘘术后临床治疗专家共识[J]. 中华小儿外科杂志, 2016, 37(8): 563-567. Neonatology Group, Pediatric Surgery Society of Chinese Medical Association. Expert consensus on clinical treatment of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis after enterostomy[J]. Chinese Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 2016, 37(8): 563-567. |

| [21] |

O'Neil M, Teitelbaum DH, Harris MB. Total body sodium depletion and poor weight gain in children and young adults with an ileostomy: a case series[J]. Nutr Clin Pract, 2014, 29(3): 397-401. |

| [22] |

Sakamoto R, Vossler J, Woo R. Predictors of morbidity following enterostomy closure in infants: an American College of Surgeons pediatric national surgical quality improvement program database analysis[J]. Hawaii J Health Soc Welf, 2021, 80(11 Suppl 3): 27-30. |

| [23] |

Bethell G, Kenny S, Corbett H. Enterostomy-related complications and growth following reversal in infants[J]. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed, 2017, 102(3): F230-F234. |