氧化三甲胺(trimethylamine-N-oxide, TMAO)是由肠道菌群对膳食化合物胆碱、肉碱与甜菜碱进行转化而来。随着现代人生活水平的提高,高脂饮食增加了TMAO的产生,肠道菌群作为一个桥梁,经其代谢产生的TMAO能对人体产生有害影响。本文主要从肠道菌群在TMAO产生过程中所发挥的作用、TMAO对肠道菌群的影响、肠道菌群通过TMAO影响肾脏和肠道在“肾-肠轴”中的作用,以及从“肾-肠轴”出发探讨TMAO与肾肠和腹泻之间的关系进行综述。

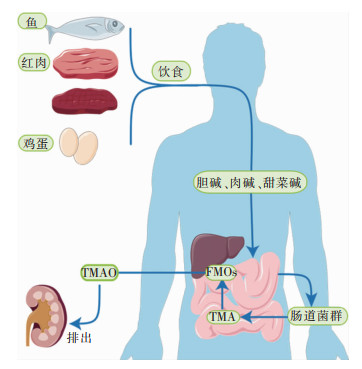

1 肠道菌群对TMAO形成的影响 1.1 肠道菌群是TMAO形成过程中的关键肠道菌群是生活在人体肠道(GI)内的正常微生物的集合[1],如双歧杆菌和乳酸杆菌等,可以合成人体生长发育所必需的多种维生素,是生态系统中最重要的活跃部分。肠道菌群被认为是人体最大的内分泌器官,经其分泌的代谢物可以被人体宿主的专用受体系统感知[2],其代谢产物和信号分子的产生,可以影响相应器官的功能[3]。当肠道菌群生态系统平衡时,肠道菌群则发挥着维持人体的免疫稳态和代谢功能的作用[1],若肠道菌群生态失调,可导致相应的不良表征[4]。TMAO是一种低分子量化合物,一般认为由胆碱、肉碱和甜菜碱经结肠内的肠道菌群代谢而来,主要由肾清除[5],部分通过肾小管细胞分泌排出,可通过血液透析有效祛除。富含磷脂酰胆碱(phosphatidyl choline, PC)的膳食是TMAO的主要来源,如:鸡蛋、肉类、肝脏、鱼等[6-7],PC随后在磷脂酶D酶的作用下转化为胆碱,再被肠道菌群中的三甲胺裂解酶代谢生成三甲胺(trimethylamine, TMA)[8]。甜菜碱和肉碱亦能转换为TMAO。甜菜碱主要存在于蔬菜中,通过甜菜碱还原酶在偶联还原-氧化反应中还原为TMA。左旋肉碱主要来源于红肉,可通过左旋肉碱氧化还原酶转化为TMA,亦可分别通过左旋肉碱脱氢酶和肉碱辅酶A转移酶转化为甜菜碱和γ-丁基甜菜碱(γ-BB)两种前体[9]。TMA被人体有效吸收入血后通过循环转移到肝脏,然后快速地被肝脏黄素单加氧酶(hepatic flavin monooxygenase, FMO)家族酶,如FMO1、FMO3,氧化催化成TMAO[10],最终经肾随尿液有效排出,见图 1。

|

| 图 1 TMAO的形成机制 |

TMA是一种高度挥发性的叔胺,有腐烂鱼的恶臭气味,被FMO氧化后生成无味的TMAO[11]。该氧化功能异常或FMO缺陷,会导致三甲胺尿症(trimethylaminuria, TMAU),又名“鱼臭综合征”,患者通过呼吸、汗、尿以及其他身体分泌物排出高水平的TMA,恶臭难闻[12]。经培养,发现厚壁菌门、变形杆菌门和放线菌门参与TMA的生产,氢厌氧球菌、天冬梭菌与梭状芽孢杆菌均参与生成TMA[13-15]。高脂肪饮食损伤结肠上皮线粒体的生物能量,增加氧气和硝酸盐的腔内生物利用度,从而加剧大肠埃希菌的呼吸依赖性胆碱分解代谢,提高TMAO水平[16]。

TMAO浓度亦与肠道菌群的组成密切相关。TMAO与普雷沃特氏菌、光冈菌、梭杆菌、脱硫弧菌、产甲烷菌等13个属的丰度有关[17]。最近一项研究[18]量化并表征了编码负责TMA产生酶的细菌基因,包括胆碱-TMA裂解酶(CutC),肉碱加氧酶(CntA)和甜菜碱还原酶(GrdH),其中携带CutC和GrdH的细菌主要隶属于厚壁菌中的各种分类群,而CntA由主要与埃希菌相关的序列组成。Li等[19]在多变量分类群范围的关联分析中确定了10种细菌物种,发现其丰度与血浆TMAO浓度显著相关,一些功能特征,包括胆碱三甲胺裂解酶激活酶,亦与TMAO浓度相关。同时,失衡的TMAO亦能对肠道菌群产生一定的影响,经胆碱饲料喂养的小鼠血浆TMAO水平升高显著,对粪便进行16S rDNA分析后发现其虽对菌群的多样性和组成结构影响不显著,但在属水平上,与对照组相比,胆碱组显著提高ruminococcaceae UCG-013的相对丰度,显著降低parasutterella的相对丰度[20]。Zhang等[21]通过16S rRNA基因测序分析人类供体粪便标本和所有无菌小鼠受体的盲肠内容物中的微生物群落扩增子序列变异(amplicon sequence variant, ASV)结构,进行差异丰度分析后发现盲肠细菌类群(即ASV)的丰度与血浆TMAO水平密切相关。高循环水平的TMAO与动脉粥样硬化(atherosclerosis, AS)[22]、代谢综合征(metabolic syndrome, MS)[23]、2型糖尿病(type 2 diabetes, T2B)[24]、肥胖[25]、移植物抗宿主病(graft-versus-host disease, GVHD)[26]等疾病密切相关,且TMAO可能是心血管疾病(cardiovascular disease, CVD)、慢性肾脏病(chronic kidney disease, CKD)的预后标志物已经得到较为广泛的认可。

2 TMAO对肾的影响 2.1 TMAO对肾功能的影响TMAO是一种含氮化合物,是源自微生物代谢的尿毒症毒素的原型。TMAO水平升高与肾小管间质纤维化、胶原沉积的相应增加以及Smad3(TGF-β信号传导的关键介质,介导肾炎症和纤维化)的磷酸化有关[27],通过激活p38/MAPK信号传导和上调HuR来加重肾损伤[28]。Kapetanaki等[29]发现TMAO通过PERK/Akt/mTOR途径,NLRP3和半胱天冬酶-1信号传导促进肾成纤维细胞的活化、增殖并增加胶原蛋白的产生。TMAO水平随着肾功能下降而升高,CKD是最常见的肾脏疾病,其特征是随着时间的推移,器官功能逐渐丧失,损伤从血液中过滤代谢废物的能力,使得TMAO水平升高。高循环的TMAO浓度与肾功能损伤之间呈正相关,能够促进肾脏的不良病理变化,如肾纤维化、肾小管功能丧失和肾小球滤过率(glomerular filtration rate, eGFR)降低等[30-31]。且CKD患者越是晚期,血清TMAO水平越高,eGFR越低[32],从而加剧TMAO累积,形成恶性循环。eGFR是肾功能的重要指标,用于CKD的诊断和CKD进展的评估,eGFR的常见生物标志物是胱抑素C和肌酐,Tang等[33]发现,无论是在胱抑素C水平高还是低的CKD受试者中,较高水平的TMAO预示着较差的生存率。Castillo-Rodriguez等[34]发现在肾功能正常的受试者中,TMAO与病死率无关,但TMAO与病死率的关联被肾功能改变,使得TMAO与病死率的关联在eGFR较低的受试者中更强。临床研究[35]发现,透析患者的血浆TMAO水平比正常受试者高出约40倍,且TMAO水平达到正常的倍数远大于尿素的水平,若透析处方基于尿素,容易导致TMAO累积到正常值的更高倍数。CKD可被视为一种代谢障碍,反映了代谢产物和信号分子在器官之间流动的中断,并伴有免疫系统的过度激活。

2.2 TMAO通过炎症机制促进肾功能损伤炎症的生物标志物与肾功能测量呈负相关,与蛋白尿呈正相关,在慢性肾功能不全队列中,细胞因子白细胞介素-1β、白细胞介素-1受体拮抗剂、白细胞介素-6、肿瘤坏死因子-α以及高敏感性C反应蛋白和纤维蛋白原的血浆水平在eGFR水平降低的受试者中较高[36]。

TMAO水平与炎症相关,TMAO诱导低度炎症的机制之一是激活非典型核转录因子-κB(NF-κB)信号通路。NF-κB通路通常被认为是一种典型的促炎信号通路,是调节炎症免疫细胞活化、分化和效应功能的重要介质[37],Zeisel等[38]发现TMAO可以激活丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(MAPK)和NF-κB信号通路,从而导致主动脉内皮细胞和平滑肌细胞中促炎因子(包括促炎细胞因子,黏附分子和趋化因子)的表达增加。同时高循环水平的TMAO下调了外周组织和中枢神经系统(CNS)中的抗炎介质RGS10,这可能会增加炎症诱导的NF-kB活性的敏感性与炎症介质的产生[39]。研究[38]表明非典型NF-κB通路与IgA肾病(immunoglobin A nephropathy, IgAN)的发病机制有关,IgAN是原发性肾小球肾炎的主要原因,其特征是糖基化IgA的异常产生和肾小球中IgA免疫复合物的沉积[40],NF-κB信号通路的激活能够导致体内肾小球硬化和蛋白尿[41]、损伤足细胞(肾小囊脏层上皮细胞,podocyte)[42],在受伤足细胞中检测到白细胞介素-1、白细胞介素-4和肿瘤坏死因子-α增多,支持NF-κB激活在人肾小球疾病中的直接作用[43]。

TMAO发挥促炎作用的另一种方式是激活炎症小体[44]。TMAO能够通过SIRT3-SOD3-mtROS信号通路激活NLRP2炎症小体[45],线粒体ROS(mtROS)通过破坏线粒体转录因子A(TFAM)介导的线粒体DNA(mtDNA)维持来促进缺血性急性肾损伤中的线粒体功能障碍和炎症。不仅如此,TMAO能显著抑制ATG16L1、LC3-II和p62的表达,并以剂量和时间依赖性的方式触发激活的NLRP3炎症小体和细胞内活性氧(ROS)的产生[46]。Saaoud等[47]发现TMAO上调基因对UT诱导的内皮细胞转录组重塑和CKD/UT诱导的肾组织转录组重塑有显著贡献。

3 TMAO对肠道的影响肠道屏障系统由具备一定厚度的黏液层、肠上皮细胞(intestinal epithelial cell, IEC)、紧密连接(tight junction, TJ)、免疫细胞和肠道微生物群组成[48],按照其结构和功能可具体分为黏膜上皮屏障(机械屏障)、免疫屏障、化学屏障和微生物屏障,能够选择性地吸收水和营养物质、阻止肠道细菌异位,以及发挥肠道免疫功能,在维持肠道屏障完整性和功能方面起着重要作用。TJ能够选择性地限制小分子、水和离子的扩散,以保持黏膜上皮屏障完整性,对于保护身体免受感染和炎症起着至关重要的作用[49]。当肠道屏障的通透性被破坏时,则会导致腔内有害分子的渗透,引起黏膜免疫激活和炎症,从而促进肠道和全身疾病的发展[50-51]。

高脂饮食能够提高TMAO的循环水平、引发炎症反应和氧化应激[52]。研究[16]发现,高脂饮食在无菌小鼠中引发以结肠长度缩短、上皮化生、结肠上皮中有丝分裂数量增加,以及杯状细胞数量减少为特征的小鼠黏膜反应。免疫激活有助于黏膜屏障的破坏,促炎细胞因子的释放是肠道屏障衰竭的主要原因,一些促炎细胞因子如:肿瘤坏死因子-α、白细胞介素-4、白细胞介素-12和白细胞介素-1b能够增加TJ通透性。TMAO可能通过影响自噬体基因ATG16L1诱导的自噬和激活NLRP3炎症小体参与炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)发病机制[46]。肠道上皮屏障能够有效地防止脂多糖(LPS)吸收,被破坏后使得LPS突破肠道上皮屏障进入血液循环,导致LPS的血液循环水平升高[53],经研究LPS能够通过激活FAK-MyD4-IRAK88信号通路的Toll样受体4(TLR4)依赖性增加肠道TJ通透性并诱发肠道炎症[14]。试验表明,急性缺氧暴露的大鼠肠道组织中TLR4和NF-κB表达增加,经吡咯烷二硫代氨基甲酸(PDTC)治疗逆转上调的TLR4和NF-κB后,能够减轻肠道屏障功能损伤和细菌异位[54]。同时IBD患者肠黏膜组织中单羧酸转运蛋白4(MCT4)的表达显著增加[55],且研究[56]表明MCT4增强NF-κB-CBP的相互作用,溶解CREB-CBP复合物,降低cAMP应答元件结合蛋白(cAMP response element binding protein, CREB)活性和CREB介导的ZO-1表达,从而促进NF-κB p65的核异位,增加NF-κB p65与IL-6启动子的结合与促炎症因子的表达,进一步破坏肠上皮屏障功能。总之,TMAO能够通过促进炎症反应,破坏肠道屏障并增加其通透性,从而使肠内细菌异位,进入血液循环,对机体造成有害影响。

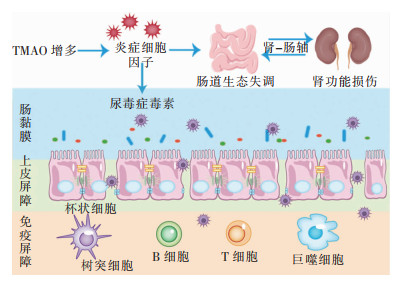

4 TMAO在肾肠功能影响中的作用 4.1 肠道生态失调与肾功能受损Podolsky等[57]首次把肠道生态失调定义为肠道微生物群落不平衡,肠道微生物群的组成和代谢活动发生定量和定性变化。“肾-肠轴”在CKD中是肠道生态失调与肾功能损伤之间的双向作用:摄入营养物质后,氨基酸分解代谢最终产物氨通过肝脏代谢转化为尿素并释放到循环中,若肾功能受损则会将主要的排泄部位由肾脏转到结肠,结肠中尿素的持续存在使产生尿素酶的细菌增殖,导致肠道生态失调,在CKD发展过程中产生炎症、内分泌和神经通路的不良影响,见图 2。研究[58]发现抑制NLRP3炎症小体可以对抗TMAO诱导的骨髓来源巨噬细胞中的M1极化,减少M2巨噬细胞,故而可以通过肠肾轴靶向巨噬细胞表型的药理学治疗肾纤维化,同时NNLRP3炎症小体亦是葡聚糖硫酸钠结肠炎模型中肠道炎症的关键机制[59]。腹膜透析是终末期肾病的肾替代疗法,通过腹膜透析患者的“肾-肠轴”研究发现其α多样性较低,肠道微生物群组成发生改变;在属水平上,致病菌丰度增加,有益菌丰度降低,其中无尿患者血清TMAO水平显著升高[60]。肾清除率不足会导致肠道菌群代谢产生的尿毒症毒素(如IS、PCS和TMA)的累积[61-62],尿毒症毒素的累积可导致CKD动物肠道黏膜中的紧密连接蛋白明显减少并破坏结肠上皮TJ,导致肠道屏障功能受损[63]。

|

| 图 2 TMAO通过“肾-肠轴”导致肠道生态失调和肾功能损伤 |

腹泻与肠道菌群的变化有关,肠道菌群通过TMAO影响“肾-肠轴”传递炎症反应与氧化应激影响泄泻。平衡的肠道菌群能够抵抗腹泻病原体的定植,对腹泻感染具有重要的保护作用[64]。TMAO能够引起炎症反应,炎症相关分子可通过“肾-肠轴”传递调控炎症反应引起泄泻[65]。肠易激综合征(irritable bowel syndrome, IBS)是一种功能性肠道疾病,以慢性或复发性腹痛为特征,伴排便缓解或加重或排便习惯改变[66]。IBS的发病机制与内脏超敏反应、GI蠕动、肠道通透性改变、免疫调节、肠道菌群改变和“脑-肾-肠轴”功能障碍有关,可进一步分为4种亚型,包括腹泻型IBS(IBS-D)、便秘型IBS(IBS-C)、混合型IBS(IBS-M)以及未分类的亚型[67]。研究[68]发现,接受IBS-D粪便微生物群的小鼠表现出更快的胃肠道运输、肠道屏障功能障碍、先天免疫激活以及焦虑样行为,表明肠道菌群可能有助于IBS-D的肠道和行为表现。氧化应激相关分子通过“肾-肠轴”传递参与机体氧化应激过程影响泄泻。ROS在体内少量产生,参与细胞调节、稳态维持、信号转导、基因表达和受体激活等功能,若ROS产生过多则会导致细胞功能障碍,如能量代谢丧失、细胞信号传导中断、免疫激活和炎症。研究[47]发现,TMAO-ER应激介质PERK通路能上调线粒体调节因子PLIN4、OMA1和OGDHL,并下调DARS2的表达,诱导线粒体ROS生成和线粒体应激。过氧化麦角甾醇可以通过干扰猪流行性腹泻病毒(porcine epidemic diarrhoea virus, PEDV)诱导的ROS产生和p53激活来抑制细胞凋亡,阻止PEDV内化、复制和释放[69]。

5 总结与展望综上所述,TMAO是由肠道菌群代谢胆碱、肉碱与甜菜碱等膳食底物后经FMOs氧化产生的有害代谢产物,失衡的TMAO能对肠道菌群产生一定的影响。肠道菌群通过TMAO影响肠道及肾在“肾-肠轴”中的作用,主要通过激发炎症反应导致肾功能损伤,诱发肾纤维化、肾小管功能丧失和肾小球滤过率降低等不良病理变化;且TMAO能够增加肠道通透性,造成肠道屏障破坏和细菌异位。同时通过“肾-肠轴”理论讨论了TMAO通过“肾-肠轴”激发炎症反应与氧化应激参与腹泻的发生发展。现代人的高脂饮食使肠道菌群产生了更多的TMAO,虽然TMAO诱导疾病损伤的机制目前已有较多研究,但确切且直接的治病机制尚未完全明晰,因此无法做到准确的靶向治疗。通过本综述对相关致病机制的阐述,希望能为未来的相关治疗提供一些思路和方向。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Arumugam M, Raes J, Pelletier E, et al. Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome[J]. Nature, 2011, 473(7346): 174-180. DOI:10.1038/nature09944 |

| [2] |

Brown JM, Hazen SL. The gut microbial endocrine organ: bacterially derived signals driving cardiometabolic diseases[J]. Annu Rev Med, 2015, 66: 343-359. DOI:10.1146/annurev-med-060513-093205 |

| [3] |

Rajilić-Stojanović M. Function of the microbiota[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2013, 27(1): 5-16. DOI:10.1016/j.bpg.2013.03.006 |

| [4] |

Witkowski M, Weeks TL, Hazen SL. Gut microbiota and cardiovascular disease[J]. Circ Res, 2020, 127(4): 553-570. DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316242 |

| [5] |

Wang ZN, Bergeron N, Levison BS, et al. Impact of chronic dietary red meat, white meat, or non-meat protein on trimethylamine N-oxide metabolism and renal excretion in healthy men and women[J]. Eur Heart J, 2019, 40(7): 583-594. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehy799 |

| [6] |

Catucci G, Querio G, Sadeghi SJ, et al. Enzymatically produced trimethylamine N-oxide: conserving it or eliminating it[J]. Catalysts, 2019, 9(12): 1028. DOI:10.3390/catal9121028 |

| [7] |

Wiedeman AM, Barr SI, Green TJ, et al. Dietary choline intake: current state of knowledge across the life cycle[J]. Nutrients, 2018, 10(10): 1513. DOI:10.3390/nu10101513 |

| [8] |

Tang WHW, Wang ZN, Levison BS, et al. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk[J]. N Engl J Med, 2013, 368(17): 1575-1584. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1109400 |

| [9] |

Koeth RA, Lam-Galvez BR, Kirsop J, et al. l-Carnitine in omnivorous diets induces an atherogenic gut microbial pathway in humans[J]. J Clin Invest, 2019, 129(1): 373-387. |

| [10] |

Luo TT, Guo ZG, Liu D, et al. Deficiency of PSRC1 accelera-tes atherosclerosis by increasing TMAO production via ma-nipulating gut microbiota and flavin monooxygenase 3[J]. Gut Microbes, 2022, 14(1): 2077602. DOI:10.1080/19490976.2022.2077602 |

| [11] |

Schmidt AC, Hebels ER, Weitzel C, et al. Engineered polymersomes for the treatment of fish odor syndrome: a first randomized double blind olfactory study[J]. Adv Sci (Weinh), 2020, 7(8): 1903697. DOI:10.1002/advs.201903697 |

| [12] |

Schmidt AC, Leroux JC. Treatments of trimethylaminuria: where we are and where we might be heading[J]. Drug Discov Today, 2020, 25(9): 1710-1717. DOI:10.1016/j.drudis.2020.06.026 |

| [13] |

Armet AM, Deehan EC, O'Sullivan AF, et al. Rethinking healthy eating in light of the gut microbiome[J]. Cell Host Microbe, 2022, 30(6): 764-785. DOI:10.1016/j.chom.2022.04.016 |

| [14] |

Romano KA, Vivas EI, Amador-Noguez D, et al. Intestinal microbiota composition modulates choline bioavailability from diet and accumulation of the proatherogenic metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide[J]. mBio, 2015, 6(2): e02481. |

| [15] |

Martínez-del Campo A, Bodea S, Hamer HA, et al. Characterization and detection of a widely distributed gene cluster that predicts anaerobic choline utilization by human gut bacteria[J]. mBio, 2015, 6(2): e00042-15. |

| [16] |

Yoo W, Zieba JK, Foegeding NJ, et al. High-fat diet-induced colonocyte dysfunction escalates microbiota-derived trimethy-lamine N-oxide[J]. Science, 2021, 373(6556): 813-818. DOI:10.1126/science.aba3683 |

| [17] |

Fu BC, Hullar MAJ, Randolph TW, et al. Associations of plasma trimethylamine N-oxide, choline, carnitine, and betai-ne with inflammatory and cardiometabolic risk biomarkers and the fecal microbiome in the multiethnic cohort adiposity phenotype study[J]. Am J Clin Nutr, 2020, 111(6): 1226-1234. DOI:10.1093/ajcn/nqaa015 |

| [18] |

Rath S, Rud T, Pieper DH, et al. Potential TMA-Producing bacteria are ubiquitously found in mammalia[J]. Front Microbiol, 2019, 10: 2966. |

| [19] |

Li J, Li YP, Ivey KL, et al. Interplay between diet and gut microbiome, and circulating concentrations of trimethylamine N-oxide: findings from a longitudinal cohort of US men[J]. Gut, 2022, 71(4): 724-733. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322473 |

| [20] |

王茜茜, 张婷, 梁明, 等. 罗伊氏乳杆菌CCFM8631对由胆碱导致的血浆氧化三甲胺和盲肠三甲胺水平升高的影响[J]. 食品与发酵工业, 2022, 48(16): 11-17. Wang QQ, Zhang T, Liang M, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus reuteri CCFM8631 on choline-induced elevation of plasma trimethylamine-N-oxide and cecal trimethylamine levels[J]. Food and Fermentation Industries, 2022, 48(16): 11-17. DOI:10.13995/j.cnki.11-1802/ts.031344 |

| [21] |

Zhang WC, Miikeda A, Zuckerman J, et al. Inhibition of microbiota-dependent TMAO production attenuates chronic kidney disease in mice[J]. Sci Rep, 2021, 11(1): 518. DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-80063-0 |

| [22] |

Wang ZN, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease[J]. Nature, 2011, 472(7341): 57-63. DOI:10.1038/nature09922 |

| [23] |

Chen SF, Henderson A, Petriello MC, et al. Trimethylamine N-oxide binds and activates PERK to promote metabolic dysfunction[J]. Cell Metab, 2019, 30(6): 1141-1151.e5. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2019.08.021 |

| [24] |

Tanase DM, Gosav EM, Neculae E, et al. Role of gut microbiota on onset and progression of microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (T2DM)[J]. Nutrients, 2020, 12(12): 3719. DOI:10.3390/nu12123719 |

| [25] |

Dehghan P, Farhangi MA, Nikniaz L, et al. Gut microbiota-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) potentially increases the risk of obesity in adults: an exploratory systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis[J]. Obes Rev, 2020, 21(5): e12993. DOI:10.1111/obr.12993 |

| [26] |

Hayase E, Jenq RR. Too much TMAO and GVHD[J]. Blood, 2020, 136(4): 383-385. DOI:10.1182/blood.2020006104 |

| [27] |

Wu WJ, Wang XQ, Yu XQ, et al. Smad3 signatures in renal inflammation and fibrosis[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2022, 18(7): 2795-2806. DOI:10.7150/ijbs.71595 |

| [28] |

Lai YS, Tang HE, Zhang XR, et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide aggravates kidney injury via activation of p38/MAPK signaling and upregulation of HuR[J]. Kidney Blood Press Res, 2022, 47(1): 61-71. DOI:10.1159/000519603 |

| [29] |

Kapetanaki S, Kumawat AK, Persson K, et al. The fibrotic effects of TMAO on human renal fibroblasts is mediated by NLRP3, caspase-1 and the PERK/Akt/mTOR pathway[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2021, 22(21): 11864. DOI:10.3390/ijms222111864 |

| [30] |

Zeng Y, Guo M, Fang X, et al. Gut microbiota-derived trimethylamine N-oxide and kidney function: a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Adv Nutr, 2021, 12(4): 1286-1304. DOI:10.1093/advances/nmab010 |

| [31] |

Gupta N, Buffa JA, Roberts AB, et al. Targeted inhibition of gut microbial trimethylamine N-oxide production reduces renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis and functional impairment in a murine model of chronic kidney disease[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2020, 40(5): 1239-1255. DOI:10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314139 |

| [32] |

Gruppen EG, Garcia E, Connelly MA, et al. TMAO is associated with mortality: impact of modestly impaired renal function[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1): 13781. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-13739-9 |

| [33] |

Tang WHW, Wang ZN, Kennedy DJ, et al. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway contri-butes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease[J]. Circ Res, 2015, 116(3): 448-455. DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305360 |

| [34] |

Castillo-Rodriguez E, Fernandez-Prado R, Esteras R, et al. Impact of altered intestinal microbiota on chronic kidney di-sease progression[J]. Toxins (Basel), 2018, 10(7): 300. DOI:10.3390/toxins10070300 |

| [35] |

Hai X, Landeras V, Dobre MA, et al. Mechanism of prominent trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) accumulation in hemodialysis patients[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(12): e0143731. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0143731 |

| [36] |

Gupta J, Mitra N, Kanetsky PA, et al. Association between albuminuria, kidney function, and inflammatory biomarker profile in CKD in CRIC[J]. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2012, 7(12): 1938-1946. DOI:10.2215/CJN.03500412 |

| [37] |

Yu H, Lin LB, Zhang ZQ, et al. Targeting NF-κB pathway for the therapy of diseases: mechanism and clinical study[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2020, 5(1): 209. DOI:10.1038/s41392-020-00312-6 |

| [38] |

Zeisel SH, Warrier M. Trimethylamine N-oxide, the microbiome, and heart and kidney disease[J]. Annu Rev Nutr, 2017, 37: 157-181. DOI:10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064732 |

| [39] |

Zhang YN, Zhang CL, Li HO, et al. The presence of high levels of circulating trimethylamine N-oxide exacerbates central and peripheral inflammation and inflammatory hyperalgesia in rats following carrageenan injection[J]. Inflammation, 2019, 42(6): 2257-2266. DOI:10.1007/s10753-019-01090-2 |

| [40] |

Zhang HS, Sun SC. NF-κB in inflammation and renal diseases[J]. Cell Biosci, 2015, 5: 63. DOI:10.1186/s13578-015-0056-4 |

| [41] |

Danilewicz M, Wagrowska-Danilewicz M. The immunoexpression of glomerular NF-κB in proteinuric patients with proliferative and non-proliferative glomerulopathies[J]. Pol J Pathol, 2013, 64(2): 78-83. |

| [42] |

Ke GB, Chen XQ, Liao RY, et al. Receptor activator of NF-κB mediates podocyte injury in diabetic nephropathy[J]. Kidney Int, 2021, 100(2): 377-390. DOI:10.1016/j.kint.2021.04.036 |

| [43] |

Zheng L, Sinniah R, Hsu SIH. In situ glomerular expression of activated NF-kappaB in human lupus nephritis and other non-proliferative proteinuric glomerulopathy[J]. Virchows Arch, 2006, 448(2): 172-183. DOI:10.1007/s00428-005-0061-9 |

| [44] |

Zhang XL, Li YN, Yang PZ, et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide promotes vascular calcification through activation of NLRP3 (nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family, pyrin domain-containing-3) inflammasome and NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) signals[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2020, 40(3): 751-765. DOI:10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.313414 |

| [45] |

Chen ML, Zhu XH, Ran L, et al. Trimethylamine-N-oxide induces vascular inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through the SIRT3-SOD2-mtROS signaling pathway[J]. J Am Heart Assoc, 2017, 6(9): e006347. DOI:10.1161/JAHA.117.006347 |

| [46] |

Yue CC, Yang XD, Li J, et al. Trimethylamine N-oxide prime NLRP3 inflammasome via inhibiting ATG16L1-induced autophagy in colonic epithelial cells[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2017, 490(2): 541-551. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.06.075 |

| [47] |

Saaoud F, Liu L, Xu KM, et al. Aorta- and liver-generated TMAO enhances trained immunity for increased inflammation via ER stress/mitochondrial ROS/glycolysis pathways[J]. JCI insight, 2023, 8(1): e158183. DOI:10.1172/jci.insight.158183 |

| [48] |

Meijers B, Farré R, Dejongh S, et al. Intestinal barrier function in chronic kidney disease[J]. Toxins (Basel), 2018, 10(7): 298. DOI:10.3390/toxins10070298 |

| [49] |

Lee JY, Wasinger VC, Yau YY, et al. Molecular pathophysiology of epithelial barrier dysfunction in inflammatory bowel diseases[J]. Proteomes, 2018, 6(2): 17. DOI:10.3390/proteomes6020017 |

| [50] |

Odenwald MA, Turner JR. The intestinal epithelial barrier: a therapeutic target?[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2017, 14(1): 9-21. DOI:10.1038/nrgastro.2016.169 |

| [51] |

Suzuki T. Regulation of the intestinal barrier by nutrients: the role of tight junctions[J]. Anim Sci J, 2020, 91(1): e13357. DOI:10.1111/asj.13357 |

| [52] |

Van Hecke T, Jakobsen LMA, Vossen E, et al. Short-term beef consumption promotes systemic oxidative stress, TMAO formation and inflammation in rats, and dietary fat content modulates these effects[J]. Food Funct, 2016, 7(9): 3760-3771. DOI:10.1039/C6FO00462H |

| [53] |

Mohammad S, Thiemermann C. Role of metabolic endotoxe-mia in systemic inflammation and potential interventions[J]. Front Immunol, 2020, 11: 594150. |

| [54] |

Luo H, Guo P, Zhou QQ. Role of TLR4/NF-κB in damage to intestinal mucosa barrier function and bacterial translocation in rats exposed to hypoxia[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(10): e46291. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0046291 |

| [55] |

He LY, Wang HL, Zhang YH, et al. Evaluation of monocarboxylate transporter 4 in inflammatory bowel disease and its potential use as a diagnostic marker[J]. Dis Markers, 2018, 2018: 2649491. |

| [56] |

Zhang SX, Xu WF, Wang HL, et al. Inhibition of CREB-mediated ZO-1 and activation of NF-κB-induced IL-6 by colonic epithelial MCT4 destroys intestinal barrier function[J]. Cell Prolif, 2019, 52(6): e12673. DOI:10.1111/cpr.12673 |

| [57] |

Podolsky SH. Metchnikoff and the microbiome[J]. Lancet, 2012, 380(9856): 1810-1811. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62018-2 |

| [58] |

Xie YN, Hu XF, Li SL, et al. Pharmacological targeting macrophage phenotype via gut-kidney axis ameliorates renal fibrosis in mice[J]. Pharmacol Res, 2022, 178: 106161. DOI:10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106161 |

| [59] |

Bauer C, Duewell P, Mayer C, et al. Colitis induced in mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) is mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome[J]. Gut, 2010, 59(9): 1192-1199. DOI:10.1136/gut.2009.197822 |

| [60] |

Bao MC, Zhang P, Guo SL, et al. Altered gut microbiota and gut-derived p-cresyl sulfate serum levels in peritoneal dialysis patients[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2022, 12: 639624. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2022.639624 |

| [61] |

Rossi M, Johnson DW, Xu H, et al. Dietary protein-fiber ratio associates with circulating levels of indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate in chronic kidney disease patients[J]. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2015, 25(9): 860-865. DOI:10.1016/j.numecd.2015.03.015 |

| [62] |

Mishima E, Fukuda S, Mukawa C, et al. Evaluation of the impact of gut microbiota on uremic solute accumulation by a CE-TOFMS-based metabolomics approach[J]. Kidney Int, 2017, 92(3): 634-645. DOI:10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.011 |

| [63] |

Tungsanga S, Panpetch W, Bhunyakarnjanarat T, et al. Uremia-induced gut barrier defect in 5/6 nephrectomized mice is worsened by Candida administration through a synergy of uremic toxin, lipopolysaccharide, and (1→3)-β-D-glucan, but is attenuated by Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus L34[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23(5): 2511. DOI:10.3390/ijms23052511 |

| [64] |

Li YX, Xia ST, Jiang XH, et al. Gut microbiota and diarrhea: an updated review[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2021, 11: 625210. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2021.625210 |

| [65] |

李小雅, 谭周进. 肾阳亏虚证泄泻的现代生物学内涵[J]. 世界华人消化杂志, 2022, 30(3): 119-127. Li XY, Tan ZJ. Modern biological connotation of diarrhea with kidney-Yang deficiency syndrome[J]. World Chinese Journal of Digestology, 2022, 30(3): 119-127. |

| [66] |

Pimentel M, Talley NJ, Quigley EMM, et al. Report from the multinational irritable bowel syndrome initiative 2012[J]. Gastroenterology, 2013, 144(7): e1-e5. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.049 |

| [67] |

Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders[J]. Gastroenterology, 2016, 150(6): 1393-1407.e5. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.031 |

| [68] |

De Palma G, Lynch MDJ, Lu J, et al. Transplantation of fecal microbiota from patients with irritable bowel syndrome alters gut function and behavior in recipient mice[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2017, 9(379): eaaf6397. DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6397 |

| [69] |

Liu Y, Wang X, Wang J, et al. Ergosterol peroxide inhibits porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection in Vero cells by suppressing ROS generation and p53 activation[J]. Viruses, 2022, 14(2): 402. DOI:10.3390/v14020402 |