2. 华中科技大学同济医学院附属同济医院肝脏外科, 湖北 武汉 430030

2. Department of Liver Surgery, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, China

中心静脉导管(central venous catheter, CVC)目前广泛应用于临床,可用于监测血流动力学、输液、输血、化学治疗及肠外营养[1],是危重症患者的治疗手段之一。除了穿刺部位可能发生局部皮肤感染外,还可因病原菌进入血液引发血流感染,即中心静脉导管相关血流感染(catheter-related bloodstream infection, CRBSI)。尽管随着医疗技术的不断进步,CRBSI的发病率明显下降,但仍然是中心静脉置管患者的重要并发症之一。既往研究[2-3]发现,影响CRBSI的因素包括置管部位、导管类型、置管次数、导管留置时间、肠外营养、疾病严重程度、抗菌药物使用、机械通气时间、置管条件、手卫生依从性等。CRBSI不仅增加患者的住院时间和住院费用[4],还增加患者病死率[5]。循证医学表明,集束化防控措施可以有效减少CRBSI的发生[6]。某三级甲等医院根据中心静脉置管集束化防控措施制定了更加精细的防控措施,从而降低CRBSI的发病率,现报告如下。

1 对象与方法 1.1 研究对象选取2019年1月-2020年12月该院中心静脉置管≥48 h的患者,置管包括CVC和经外周静脉中心静脉置管(PICC),肿瘤科PICC置管患者除外,患者置管前未发生血流感染。本研究取得该医院伦理委员会批准(伦理编号TJ-IRB20220134)。

1.2 监测内容2019年1-12月为干预前期,2020年1-12月为干预后期。监测内容包括CRBSI防控措施执行率和CRBSI发病率。根据美国疾病控制与预防中心(CDC)推荐的CRBSI预防措施[6]及我国2016年颁布的《重症监护病房医院感染预防与控制规范》[7],该研究制定了更加精细的CRBSI防控措施,其中由医生落实的防控措施主要有:(1)每日评估中心静脉导管留置指征;(2)置管时无菌技术规范;(3)置管时采用最大无菌屏障;(4)置管时皮肤消毒合理,宜使用有效含量≥2 g/L氯己定-乙醇溶液局部擦拭2~3遍;(5)导管类型合理,根据患者病情尽可能使用腔数较少的导管;(6)置管部位不宜选择股静脉;(7)送检合理,怀疑CRBSI时,如无禁忌证,应立即拔管,导管尖端送微生物检测,同时送静脉血微生物检测。由护士落实的防控措施主要有:(1)每日评估中心静脉导管留置指征;(2)保持穿刺点干燥,观察穿刺部位有无感染征象;(3)导管更换合理,如无感染征象,不宜常规更换导管;(4)导管敷料选用合理;(5)穿刺点敷料更换合理。

1.3 研究方法 1.3.1 监测方法由医院感染管理科专职人员每周到临床科室进行核查,根据现场观察情况或询问医务人员相应防控措施填写核查表。

1.3.2 干预措施(1) 由医院感染管理科在2019年12月底组织全院进行CRBSI集束化防控措施培训;(2)在全院范围内公布2019年各科室CRBSI集束化防控措施的核查数据和CRBSI发病率;(3)建立奖惩机制,对于防控措施执行率较低、CRBSI发病率较高的科室,取消当年优秀科室评比资格。

1.3.3 评价指标将CRBSI发病率作为评价指标,CRBSI发病率=观察期内CRBSI感染总例数/观察期内中心静脉置管总日数×1 000‰。

1.3.4 CRBSI诊断标准根据2010年卫生部颁发的《导管相关血流感染预防与控制技术指南》[8],符合下列情况可诊断为CRBSI:中心静脉置管超过48 h或者拔除中心静脉导管48 h内,患者出现菌血症或真菌血症,并伴有发热(>38℃)、寒战或低血压等临床表现,除血管导管外没有其他明确的感染源。病原学诊断:①外周静脉血培养细菌或真菌阳性;②导管尖端培养和外周血培养分离出相同种类、相同药敏结果的致病菌。

1.4 统计学方法应用SPSS 22.0统计软件对数据进行分析。计数资料用例数或百分比表示,采用χ2检验或Fisher’s确切概率法进行比较;计量资料用x±s表示,采用t检验进行比较;P≤0.05为差异有统计学意义。

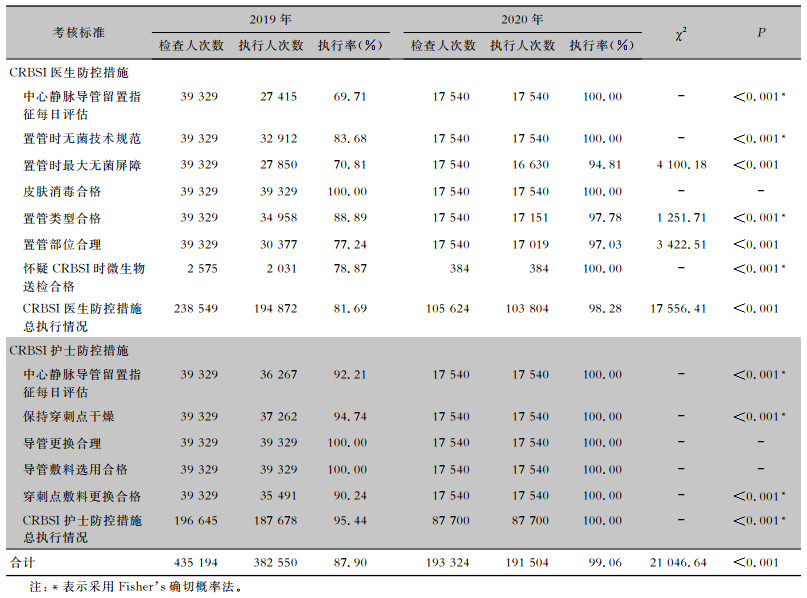

2 结果 2.1 CRBSI集束化防控措施执行情况2019年共观察CRBSI防控措施各项指标435 194次,执行382 550次,执行率为87.90%;2020年共观察CRBSI防控措施各项指标193 324次,执行191 504次,执行率为99.06%;2020年CRBSI防控措施执行率高于2019年,差异有统计学意义(χ2=21 046.64,P<0.001)。见表 1。

| 表 1 CRBSI防控措施执行情况 Table 1 Implementation of CRBSI prevention and control measures |

|

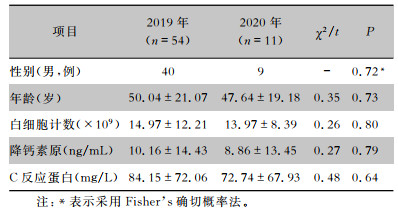

2019、2020年分别发生CRBSI 54、11例,两组感染患者性别、年龄、白细胞计数、降钙素原和C反应蛋白水平比较,差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。见表 2。2019年患者置管总日数为350 473 d,CRBSI发病率为0.15‰。2020年置管总日数为186 856 d,CRBSI发病率为0.06‰,两组患者CRBSI发病率比较差异有统计学意义(χ2=5.912,P=0.015)。

| 表 2 CRBSI患者一般资料比较 Table 2 Comparison of general information of patients with CRBSI |

|

医院内行中心静脉置管的患者往往病情较重,因此需要时刻警惕CRBSI的发生。近年来,随着医疗技术的不断改进,CRBSI的发病率也在持续下降,但每年仍有大量CRBSI感染患者。据统计,在美国每年CRBSI感染人数为84 000~204 000例,由此导致的死亡人数达25 000例左右,经济损失约210亿美元[9]。

预防CRBSI最有效的方法是减少不必要的中心静脉置管[10-11],因此每日评估拔管指征就显得尤为重要。在本研究中,研究前期部分医务人员(尤其是医生)未认识到评估拔管指征的重要性。导管留置的时间越长,发生CRBSI的风险越大[12]。可能是由于细菌生长繁殖与迁移需要一定的时间,随着导管留置时间的延长,会有大量细菌从管端入血从而引起CRBSI的发生[13]。通过不断干预,研究后期医务人员对拔管指征评估的执行率明显提高,CRBSI发病率下降。研究[14]表明置管时采取最大无菌屏障,可以有效减少CRBSI的发生。最大无菌屏障不仅是指最大铺巾,还应包括穿无菌手术衣,戴无菌手套、医用外科口罩、帽子、手术面屏等措施。在本研究中,医务人员对于最大无菌屏障的理解不够透彻,往往忽略穿无菌手术衣,戴帽子、手术面屏等措施,严格无菌技术是减少感染的根本保证。在研究前期存在有医务人员无菌技术操作不规范的情况,主要体现在置管过程中手触碰到非无菌部位,均会增加CRBSI的风险。另外,皮肤消毒合格是预防CRBSI的重要措施之一。正确的皮肤消毒包括消毒剂种类、消毒剂作用时间、消毒范围和足够的干燥时间[15]。目前国际上对于选择何种皮肤消毒剂仍然存在争议[16]。该院参照国内标准选择有效含量≥2 g/L氯己定-乙醇溶液局部擦拭2~3遍[7]。研究[17]表明,锁骨下静脉是减少血管导管相关感染并发症的首选穿刺部位。锁骨下静脉与股静脉相比,可以减少血栓和感染的发生,与颈静脉相比,同样可以减少血管导管相关感染并发症[18]。血栓形成与感染之间存在密切关系,管壁周围形成的血栓会增加导管细菌定植[19],从而增加CRBSI的风险。但锁骨下静脉穿刺也有弊端,比如不适用于短期透析置管,同时需要警惕静脉狭窄的风险[20]。在本研究中,临床医生因为各种原因,可能会选择股静脉作为中心静脉置管穿刺点,从而会增加CRBSI发病率。研究[21]发现使用多腔导管是导致CRBSI的危险因素之一。可能是由于多腔导管使用频率更高、频繁断开接头等均可增加感染风险。因此建议尽量选用腔数较少的导管。当怀疑CRBSI时,如无禁忌证,应立即拔管,导管尖端送微生物学检测,同时采集静脉血进行微生物检测。对于无法拔除导管的患者,建议采集外周静脉血进行微生物学检测,同时采集导管内血进行微生物学检测。少数临床医生在怀疑CRBSI时未规范送检,从而导致无法监测到CRBSI的相关数据。

研究[22]发现同一穿刺部位频繁更换中心静脉导管会增加CRBSI的风险。当无感染征象时,不宜常规更换导管,不宜定期对穿刺点涂抹采样送微生物学检测。如患者穿刺部位未及时更换敷料,CRBSI的感染风险增加至少3倍[23]。合理的选用和更换敷料同样可以预防CRBSI的发生。应当尽量使用无菌透明、透气性好的敷料覆盖穿刺点,对于高热、出汗以及穿刺点出血、渗出的患者应当使用无菌纱布覆盖。应当定期更换置管穿刺点覆盖的敷料。更换间隔时间为:无菌纱布为1次/2 d,无菌透明敷料为1~2次/周,如果纱布或敷料出现潮湿、松动、可见污染时应当立即更换,注意时刻保持穿刺点干燥。

本研究前期发现大部分CRBSI防控措施均有未完全落实的情况。通过培训、CRBSI感染数据公开透明化管理和奖惩机制,2020年大部分CRBSI防控措施均完全落实到位。2020年,CRBSI发病率也较前明显降低,说明实施精细化防控措施可降低CRBSI的发生。然而,影响CRBSI的因素多种多样,除了严格落实集束化防控措施以外,患者营养状况、基础疾病、置管时间、抗菌药物的使用等都可能影响CRBSI的发生,如何预防CRBSI仍需进一步探讨。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Tennent DJ, Shiels SM, Jennings JA, et al. Local control of polymicrobial infections via a dual antibiotic delivery system[J]. J Orthop Surg Res, 2018, 13(1): 53. DOI:10.1186/s13018-018-0760-y |

| [2] |

van der Kooi TII, Wille JC, van Benthem BHB. Catheter application, insertion vein and length of ICU stay prior to insertion affect the risk of catheter-related bloodstream infection[J]. J Hosp Infect, 2012, 80(3): 238-244. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2011.11.012 |

| [3] |

Çaylan R, Yılmaz G, Sözen EE, et al. Incidence and risk factors for bloodstream infections stemming from temporary hemodialysis catheters[J]. Turk J Med Sci, 2010, 40(6): 835-841. |

| [4] |

Nakamura I, Fukushima S, Hayakawa T, et al. The additio-nal costs of catheter-related bloodstream infections in intensive care units[J]. Am J Infect Control, 2015, 43(10): 1046-1049. DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.05.022 |

| [5] |

Liu HB, Liu HM, Deng J, et al. Preventing catheter-related bacteremia with taurolidine-citrate catheter locks: a systematic review and Meta-analysis[J]. Blood Purif, 2014, 37(3): 179-187. DOI:10.1159/000360271 |

| [6] |

Soni RA, Rogers G, Valenti A, et al. Catheter-related blood stream infection (CRBSI) rates in a mixed medical-surgical ICU population before and after the implementation of a central line bundle (CLB)[J]. Chest, 2008, 134(4 S2): 3S. |

| [7] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会. 重症监护病房医院感染预防与控制规范: WS/T 509—2016[S]. 北京: 中国标准出版社, 2017. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China. Regulation for prevention and control of healthcare associated infection in intensive car unit: WS/T 509-2016[S]. Beijing: Standards Press of China, 2017. |

| [8] |

中华人民共和国卫生部. 导管相关血流感染预防与控制技术指南[S]. 北京, 2010. Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. Technical guidelines for the prevention and control of catheter-related bloodstream infections: trial implementation[S]. Beijing, 2010. |

| [9] |

Umscheid CA, Mitchell MD, Doshi JA, et al. Estimating the proportion of healthcare-associated infections that are reasonably preventable and the related mortality and costs[J]. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2011, 32(2): 101-114. DOI:10.1086/657912 |

| [10] |

Laupland KB, Koulenti D, Schwebel C. The CVC and CRBSI: don't use it and lose it![J]. Intensive Care Med, 2018, 44(2): 238-240. DOI:10.1007/s00134-017-5033-4 |

| [11] |

van der Kooi T, Sax H, Pittet D, et al. Prevention of hospital infections by intervention and training (PROHIBIT): results of a pan-European cluster-randomized multicentre study to reduce central venous catheter-related bloodstream infections[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2018, 44(1): 48-60. DOI:10.1007/s00134-017-5007-6 |

| [12] |

曾翠, 李六亿, 贾会学, 等. 重症监护病房中央导管相关血流感染的干预研究[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2015, 14(8): 535-539. Zeng C, Li LY, Jia HX, et al. Study on intervention in central line-associated bloodstream infection in intensive care units[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2015, 14(8): 535-539. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-9638.2015.08.007 |

| [13] |

杜学娜, 张岩, 董爱英, 等. 中心静脉导管留置部位及时间与感染发生的相关性分析[J]. 中国临床医生杂志, 2017, 45(1): 47-49. Du XN, Zhang Y, Dong AY, et al. Correlation analysis of central venous catheter indwelling site and time with infection[J]. Chinese Journal for Clinicians, 2017, 45(1): 47-49. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.2095-8552.2017.01.016 |

| [14] |

Hu KK, Veenstra DL, Lipsky BA, et al. Use of maximal sterile barriers during central venous catheter insertion: clinical and economic outcomes[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2004, 39(10): 1441-1445. DOI:10.1086/425309 |

| [15] |

Buetti N, Timsit JF. Management and prevention of central venous catheter-related infections in the ICU[J]. Semin Respir Crit Care Med, 2019, 40(4): 508-523. DOI:10.1055/s-0039-1693705 |

| [16] |

Casey AL, Badia JM, Higgins A, et al. Skin antisepsis: it's not only what you use, it's the way that you use it[J]. J Hosp Infect, 2017, 96(3): 221-222. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2017.04.019 |

| [17] |

Parienti JJ, Mongardon N, Mégarbane B, et al. Intravascular complications of central venous catheterization by insertion site[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(13): 1220-1229. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1500964 |

| [18] |

Ge XL, Cavallazzi R, Li CB, et al. Central venous access sites for the prevention of venous thrombosis, stenosis and infection[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2012, 2012(3): CD004084. |

| [19] |

Mehall JR, Saltzman DA, Jackson RJ, et al. Fibrin sheath enhances central venous catheter infection[J]. Crit Care Med, 2002, 30(4): 908-912. DOI:10.1097/00003246-200204000-00033 |

| [20] |

Parienti JJ, Thirion M, Mégarbane B, et al. Femoral vs jugular venous catheterization and risk of nosocomial events in adults requiring acute renal replacement therapy: a randomized controlled trial[J]. JAMA, 2008, 299(20): 2413-2422. DOI:10.1001/jama.299.20.2413 |

| [21] |

范润平, 龚青霞, 巩文花, 等. ICU患者中心静脉导管血流感染危险因素的Meta分析[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2018, 17(4): 335-340. Fan RP, Gong QX, Gong WH, et al. Meta-analysis on risk factors for central venous catheter-related blood-stream infection in intensive care unit patients[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2018, 17(4): 335-340. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-9638.2018.04.012 |

| [22] |

Timsit JF, L'Hériteau F, Lepape A, et al. A multicentre analysis of catheter-related infection based on a hierarchical model[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2012, 38(10): 1662-1672. DOI:10.1007/s00134-012-2645-6 |

| [23] |

Timsit JF, Bouadma L, Ruckly S, et al. Dressing disruption is a major risk factor for catheter-related infections[J]. Crit Care Med, 2012, 40(6): 1707-1714. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e0d46 |