2. 昆明医科大学第一附属医院皮肤与性病科, 云南 昆明 650032

2. Department of Dermatology and Venereology, First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming 650032, China

所有生物都需要对生存环境中的其他微生物产生持续防御,否则可能会发生感染甚至死亡。脊椎动物机体内强大的免疫系统可将入侵的微生物清除,但是对于血液循环不能到达的部位(眼睛或皮肤表面)和没有强大免疫系统的无脊椎动物,这种防御功能主要依赖体表存在的抗菌小分子[1],这些小分子即是抗菌肽。

抗菌肽,又称宿主防御肽(host defense peptides),原指昆虫体内经诱导产生的一类具有抗菌活性的小分子肽。世界上第一个抗菌肽由瑞典科学家G.Boman等在1980年研究北美天蚕的免疫机制时发现,他们将大肠埃希菌注射到北美天蚕滞育蛹后发现其血液淋巴细胞中会产生具有抑菌作用的多肽物质,命名为Cecropins[2]。随后抗菌肽的来源不断被扩充,至今人们已经发现了2 700多种抗菌肽,来源于细菌、古细菌、原生生物、真菌、植物和动物等[3]。宿主防御肽在结构上具有两亲性,分子量一般在2 000~7 000 Da,主要由20~60个氨基酸残基组成,当处于pH值为7.4的生理环境中时,其大部分净正电荷为+2~+9,因此,也称作阳离子宿主防御肽[4]。

人体抗菌肽主要分为Defensins家族(α-defensins和β-defensins)、Cathelicidin家族(hCAP-18/LL-37)和组蛋白家族三大类[5]。Cathelicidins是一个哺乳动物抗菌肽家族,主要来源于灵长类、有蹄类和啮齿动物[6]的巨噬细胞、中性粒细胞、自然杀伤细胞以及皮肤、肠道、呼吸道和眼表的上皮细胞[7]。Cathelicidins家族的抗菌肽包含一个C-端阳离子的抗菌结构,该结构域只有在整个肽的N-端“cathelin”部分被释放后才具有活性。LL-37是在人类体内发现的唯一1种属于Cathelicidins家族的抗菌肽,该抗菌肽是由其前体蛋白hCAP-18的C-端断裂释放产生的37个氨基酸的小分子肽[8]。

1 LL-37的表达与结构LL-37由CAMP基因编码的前体蛋白hCAP-18产生,分为信号肽部分、Cathelin结构域和活性肽部分。hCAP-18基因位于3号染色体,长1 963 bp,由4个外显子组成[9],外显子1、外显子2和外显子3编码信号肽部分和Cathelin结构域部分,外显子4编码活性肽部分;LL-37的N-端为信号肽部分,由30个氨基酸残基构成,主要指导活性肽部分的释放,中间的Cathelin结构域部分由101个氨基酸残基组成,而C-末端的活性肽部分由37个氨基酸残基构成,序列为LLGFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES[10]。前体hCAP-18切除信号肽后,剩余部分主要以颗粒蛋白的形式储存在中性粒细胞或上皮细胞中,活性成分LL-37的释放还需要丝氨酸蛋白酶3将Cathelin结构域部分切除[11]。有研究[12]发现,在激活的中性粒细胞胞膜上可以检测出大量的hCAP-18富集,因此LL-37的释放主要发生在细胞膜表层。

LL-37在不同溶液中存在形式不相同,在纯水中呈现二级无序结构并形成低聚物[13],但在脂质模型、胶束溶液和离子溶液中(如碳酸氢盐、硫酸盐和氯化物盐)中为α-螺旋结构[10],研究[13]表明α-螺旋结构可更有效的杀菌。虽然LL-37被认为是人类来源的唯一Cathelicidins家族抗菌肽,但是经过不同蛋白酶对其不同位点进行水解切割会产生不同的小分子肽产物(如LL-8、SK29、LL-25和LL-15等),这些小分子肽产物也具有较强的杀菌能力,LL-25的杀菌活性比LL-37更强,但是失去了LL-37的免疫调节功能[14]。

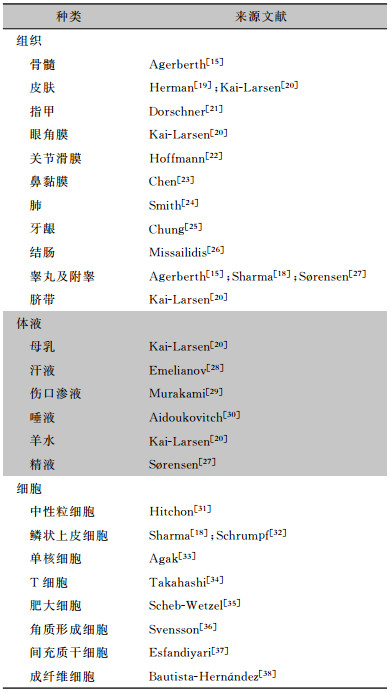

2 LL-37的组织/细胞来源LL-37最初发现于人的白细胞和睾丸中[15],随后在其他细胞、组织和体液中也相继被发现,见表 1。LL-37主要以前体hCAP-18颗粒蛋白的形式储存在溶酶体相关细胞器中[16],以便能够在机体受损时快速运转到病灶处。LL-37主要由宿主细胞受病原激活而产生,也会受其他信号通路的调控激活。研究[17]发现在A型链球菌侵袭皮肤时,真皮中的肥大细胞通过脱颗粒释放LL-37来抑制A型链球菌的感染;而肺炎链球菌在人角膜细胞中可通过激活转录激活子3(STAT3)进而增加LL-37的表达以抵抗肺炎链球菌在角膜的定植[18]。

| 表 1 LL-37表达分布汇总 |

|

最初LL-37的生物学研究重点是其抗菌活性,发现其对细菌和真菌等病原微生物均具有广谱的抗菌活性,并且对不同的微生物物种有不同的杀菌活性。

3.1 LL-37的抗细菌活性LL-37对革兰阳性菌和革兰阴性菌均具有很好的抗菌活性:对革兰阴性菌中的大肠埃希菌等[39-41]有较好杀菌作用;对革兰阳性菌中的金黄色葡萄球菌[40]和肺炎链球菌[17]等亦有抗菌活性,但对粪肠球菌[39]无作用。LL-37对细菌的抗菌活性与细菌的细胞壁成分密切相关,革兰阴性菌细胞壁含有大量的脂多糖(LPS),革兰阳性菌细胞壁外则包被大量的脂磷壁酸,两者均带负电荷,而属于阳离子宿主防御肽的LL-37带正电荷,极易与细菌细胞壁上带负电的脂磷壁酸或LPS相结合,细胞壁被破坏导致胞内物质外流和细胞壁解体,进而导致细菌死亡[8]。

随着抗菌药物的大量使用,细菌通过自身进化来抵抗药物的杀灭作用,对绝大部分的抗菌药物产生了耐药性。由于与抗菌药物的抗菌机制不同,LL-37除对敏感菌株有活性,对部分抗菌药物耐药菌株也具有较强的活性,研究[42-43]发现LL-37对耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌和多重耐药铜绿假单胞菌有很强的抗菌活性;LL-37单独使用对敏感菌株和正常菌株均有较好的抗菌活性,且在联合一些药物使用后杀菌活性更强,研究[44]表明LL-37联合反式小分子抑制剂KKL-40可以更容易杀灭金黄色葡萄球菌,联合阿奇霉素对耐碳青霉烯类铜绿假单胞菌、肺炎克雷伯菌、鲍曼不动杆菌等均具有有效杀灭作用[45]。生物膜的形成是细菌重要的耐药机制,细菌黏附于接触表面,分泌多糖基质、纤维蛋白等将自身包绕在其中而形成大量细菌聚集膜样物。生物膜一旦形成,对外来抗菌药物及机体自身免疫力有着天然的抵抗能力,抗菌药物只能杀灭生物膜表面附着细菌或者游离细菌,而难以清除生物膜包裹中的细菌,当机体抵抗力下降时,生物膜中存活的细菌又释放出来,引起再次感染。LL-37不仅可以杀灭游离的细菌,对已形成生物膜的细菌也具有杀菌作用,能通过有效地结合LPS与脂磷壁酸来达到对大肠埃希菌和金黄色葡萄球菌生物膜形成抑制和抗生物膜特性[46],Koppen等[47]发现金黄色葡萄球菌中的dltABCD操纵子和mprF基因对LL-37具有抗性,单独使用时需要较高浓度,但是联合替考拉宁时只需较低剂量便可达到破坏金黄色葡萄球菌生物膜的作用。

3.2 细菌对LL-37的抗性虽然LL-37可以有效对抗耐药细菌,但也有研究发现部分细菌已进化获得一些抵抗LL-37作用的机制。研究[48]发现变形链球菌进化获得一个由ABC转运蛋白(BceAB)和一个由四基因操纵子编码的双组分系统(BceRS)组成的四组分系统(BceABRS),该系统可使变形链球菌对LL-37产生抗性;当LL-37作用猪链球菌后会上调该菌中的半胱氨酸蛋白酶(APDS)的表达,该酶可以快速水解LL-37,减轻其对猪链球菌的杀菌活性并钝化宿主固有免疫,进而减弱对中性粒细胞的趋化性,并抑制中性粒细胞胞外陷阱(Neutrophil extracellular traps, NETs)的形成,使该菌免于被NETs杀灭[49];出血性大肠埃希菌会激活协同响应丁酸盐和LL-37的毒力基因,使OmpT蛋白酶表达上升,进而产生细菌外膜囊泡对抗LL-37[50];铜绿假单胞菌中的Mla系统可以维持外膜完整性,其中的vacJ基因可以改变宿主对铜绿假单胞菌敏感性以抵抗LL-37的抗菌作用[51];在慢性铜绿假单胞菌感染疾病中,铜绿假单胞菌会变异成皱纹小菌落变异株,促进吞噬逃逸和增强对LL-37的耐受性[52],还会变异成黏液变异株,产生过量的胞外多糖海藻酸盐抵抗LL-37的杀伤[53]。

3.3 LL-37的抗真菌活性LL-37除对细菌有较强的抗菌活性,对真菌也有抑菌杀菌作用。LL-37抗真菌的研究以白念珠菌为主,体外试验发现LL-37可以在低盐20% mDixon培养基(pH5.5)中杀灭白念珠菌[54],对其形成生物膜有一定抑制作用[46]。原代人口腔黏膜细胞在IL-17a诱导下会分泌LL-37来抵抗白念珠菌感染[55];共生厌氧细菌(特别是梭状芽孢杆菌Ⅵ簇、ⅪⅤa簇和拟杆菌)通过激活HIF-1α诱导LL-37的表达,进而抑制白念珠菌在肠道的定植[56]。

真菌为真核生物,且真菌的细胞壁和细菌的细胞壁在结构、组分和厚度上有很大的不同,因此LL-37与真菌的作用方式和细菌有很大不同。真菌细胞壁主要由两性碳水化合物和少量蛋白或者糖蛋白构成,使真菌细胞壁带负电荷量比细菌细胞壁的少;且真菌细胞壁含有大量的几丁质和葡聚糖,厚度可达100~200 nm,而细菌的细胞壁仅8 nm左右。因此,LL-37不易结合在真菌的细胞壁上,也不可能直接在上面“打孔”。Ordonez等[53]发现在低浓度的LL-37环境中,LL-37会使白念珠菌的胞壁通透性增加,使其内部液泡扩张以达到杀灭白念珠菌的效果;研究[57-59]发现LL-37会使白念珠菌的胞壁完整性发生变化,还影响白念珠菌的转运、调节及应激相关的基因表达,具体机制有:(1)LL-37可以通过与白念珠菌细胞壁主要成分甘露聚糖的优先结合和部分与甘露聚糖层的甲壳素或葡聚糖的结合来介导白念珠菌对细胞的黏附和聚集;(2)LL-37还会降低白念珠菌细胞壁成分β-1,3葡聚糖外切酶Xog1p的活性,从而中断细胞壁的重塑来抑制白念珠菌的生长。

3.4 真菌对LL-37的抗性如前所述,部分细菌种类已经针对LL-37产生了多种抗性机制,真菌也同样进化获得一些独有的自我保护机制。当LL-37与白念珠菌相互作用时,白念珠菌会脱落自身质膜上感受性蛋白Msb2的糖基化蛋白片段,使其与LL-37结合从而保护白念珠菌不受LL-37的影响[60-61];白念珠菌还可以有效的利用天冬氨酸蛋白酶剪切LL-37以破坏其抗菌和免疫调节特性[14]。

4 LL-37的免疫调节功能研究[62]发现LL-37除拥有直接抗菌作用以外,还具有强大的免疫调节功能。在2型糖尿病创面愈合不良患者中,使用大环内酯类的克拉霉素可以上调LL-37在NETs的表达,增强患者抗菌能力以促进伤口愈合,改善疾病预后;LL-37是角质细胞凋亡的调节因子,可以调节细胞因子和趋化因子来增强其抗真菌作用[63]。研究[64]还发现LL-37既可以发挥炎症诱导剂的作用,也可作为抗炎介质发挥不同的免疫调节作用:Choi等[65]发现,LL-37可以促进抗炎因子IL-IRA的产生,并通过诱导MKP-1的磷酸化来抑制IL-32诱导的炎症反应;而Beaumont等[66]则发现在铜绿假单胞菌肺炎中,外源性LL-37在没有直接杀菌活性的情况下,可以引起促炎反应诱导中性粒细胞将铜绿假单胞菌从肺中清除。LL-37在非特异性和特异性免疫反应中均扮演重要角色,具有趋化不同免疫细胞的作用,现已发现LL-37可以趋化中性粒细胞、嗜酸性粒细胞、单核细胞和T细胞[8];LL-37除了可以趋化细胞外,还可以诱导巨噬细胞分化成具有促炎特征的M1型细胞[67];树突状细胞在体外经LL-37诱导后,可以显著上调吞噬细胞的吞噬能力,促进Th1应答并释放相关炎症因子[68]。

5 展望抗菌药物耐药性是一个全球性的挑战,自从1940年青霉素被发现后,耐药性的产生也随之而来。据统计,耐药菌感染在全球造成至少70万人死亡。随着抗菌药物和糖皮质激素的广泛应用,临床耐药率也明显上升,且耐药株突变迅速。耐药性的产生降低了药物的有效性,增加感染性疾病的发病率和患者病死率,对全球公共卫生构成重大威胁[69]。人们不断寻找新的抗菌药物和结构修饰药物来对抗耐药性,但是新的抗菌药物研发进程愈发困难[70],因此,健康可持续发展的新型抗菌药物是全球应对抗菌药物耐药的关键。抗菌肽是人体天然免疫的重要组成部分,现在已从不同的人体组织中分析鉴定出100多个这样的抗菌肽,人类Cathecilindin家族LL-37研究最为深入,且LL-37和其衍生物抗微生物活性较好,这些小分子肽具有良好的溶解度、药代动力学和生物利用度,主要通过“膜破坏”机制来杀伤细胞,具有毒性低、与细胞作用时间短、不通过受体发挥作用的特点,大大减少了被微生物识别的情况,进而不容易产生耐受性,可以开发成新型的抗菌药物在医药行业具有很好的应用前景[71]。但是依旧存在一些问题:①药效动力学、毒理学及潜在免疫毒性问题;②分子量小,分离纯化困难且容易降解;③天然资源有限,化学和基因工程合成则成本高、生产效率低;④与传统抗菌药物相比较,有部分抗菌肽衍生物活性还不够理想。但是值得注意的是现在对其进行修饰使其性质更佳的报道也愈来愈多,在医药行业具有很大的潜力。

| [1] |

Bucki R, Leszczyńska K, Namiot A, et al. Cathelicidin LL-37: a multitask antimicrobial peptide[J]. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz), 2010, 58(1): 15-25. DOI:10.1007/s00005-009-0057-2 |

| [2] |

Steiner H, Hultmark D, Engström A, et al. Sequence and specificity of two antibacterial proteins involved in insect immunity[J]. Nature, 1981, 292(5820): 246-248. DOI:10.1038/292246a0 |

| [3] |

Wang GS, Li X, Wang Z. APD3: the antimicrobial peptide database as a tool for research and education[J]. Nucleic Acids Res, 2016, 44(D1): D1087-D1093. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkv1278 |

| [4] |

Choi KY, Chow LN, Mookherjee N. Cationic host defence peptides: multifaceted role in immune modulation and inflammation[J]. J Innate Immun, 2012, 4(4): 361-370. |

| [5] |

De Smet K, Contreras R. Human antimicrobial peptides: defensins, cathelicidins and histatins[J]. Biotechnol Lett, 2005, 27(18): 1337-1347. DOI:10.1007/s10529-005-0936-5 |

| [6] |

Żelechowska P, Agier J, Kozłowska E, et al. Alternatives for antibiotics - antimicrobial peptides and phages[J]. Przegl Lek, 2016, 73(5): 334-339. |

| [7] |

Kahlenberg JM, Kaplan MJ. Little peptide, big effects: the role of LL-37 in inflammation and autoimmune disease[J]. J Immunol, 2013, 191(10): 4895-4901. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1302005 |

| [8] |

Agier J, Efenberger M, Brzezińska-Błaszczyk E. Cathelicidin impact on inflammatory cells[J]. Cent Eur J Immunol, 2015, 40(2): 225-235. |

| [9] |

Gudmundsson GH, Agerberth B, Odeberg J, et al. The human gene FALL39 and processing of the cathelin precursor to the antibacterial peptide LL-37 in granulocytes[J]. Eur J Biochem, 1996, 238(2): 325-332. DOI:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0325z.x |

| [10] |

Dürr UH, Sudheendra US, Ramamoorthy A. LL-37, the only human member of the cathelicidin family of antimicrobial peptides[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2006, 1758(9): 1408-1425. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.03.030 |

| [11] |

Sørensen OE, Follin P, Johnsen AH, et al. Human cathelicidin, hCAP-18, is processed to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by extracellular cleavage with proteinase 3[J]. Blood, 2001, 97(12): 3951-3959. DOI:10.1182/blood.V97.12.3951 |

| [12] |

Stie J, Jesaitis AV, Lord CI, et al. Localization of hCAP-18 on the surface of chemoattractant-stimulated human granulocytes: analysis using two novel hCAP-18-specific monoclonal antibodies[J]. J Leukoc Biol, 2007, 82(1): 161-172. DOI:10.1189/jlb.0906586 |

| [13] |

Johansson J, Gudmundsson GH, Rottenberg ME, et al. Conformation-dependent antibacterial activity of the naturally occurring human peptide LL-37[J]. J Biol Chem, 1998, 273(6): 3718-3724. DOI:10.1074/jbc.273.6.3718 |

| [14] |

Rapala-Kozik M, Bochenska O, Zawrotniak M, et al. Inactivation of the antifungal and immunomodulatory properties of human cathelicidin LL-37 by aspartic proteases produced by the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans[J]. Infect Immun, 2015, 83(6): 2518-2530. DOI:10.1128/IAI.00023-15 |

| [15] |

Agerberth B, Gunne H, Odeberg J, et al. FALL-39, a putative human peptide antibiotic, is cysteine-free and expressed in bone marrow and testis[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1995, 92(1): 195-199. DOI:10.1073/pnas.92.1.195 |

| [16] |

Griffiths GM. Secretion from myeloid cells: secretory lysosomes[J]. Microbiol Spectr, 2016, 4(4): 593-597. |

| [17] |

Clark M, Kim J, Etesami N, et al. Group A Streptococcus prevents mast cell degranulation to promote extracellular trap formation[J]. Front Immunol, 2018, 9: 327. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00327 |

| [18] |

Sharma P, Sharma N, Mishra P, et al. Differential expression of antimicrobial peptides in Streptococcus pneumoniae keratitis and STAT3-dependent expression of LL-37 by Streptococcus pneumoniae in human corneal epithelial cells[J]. Pathogens, 2019, 8(1): 31. DOI:10.3390/pathogens8010031 |

| [19] |

Herman A, Herman AP. Antimicrobial peptides activity in the skin[J]. Skin Res Technol, 2019, 25(2): 111-117. DOI:10.1111/srt.12626 |

| [20] |

Kai-Larsen Y, Gudmundsson GH, Agerberth B. A review of the innate immune defence of the human foetus and newborn, with the emphasis on antimicrobial peptides[J]. Acta Paediatr, 2014, 103(10): 1000-1008. DOI:10.1111/apa.12700 |

| [21] |

Dorschner RA, Lopez-Garcia B, Massie J, et al. Innate immune defense of the nail unit by antimicrobial peptides[J]. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2004, 50(3): 343-348. DOI:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.010 |

| [22] |

Hoffmann MH, Bruns H, Bäckdahl L, et al. The cathelicidins LL-37 and rCRAMP are associated with pathogenic events of arthritis in humans and rats[J]. Ann Rheum Dis, 2013, 72(7): 1239-1248. DOI:10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202218 |

| [23] |

Chen PH, Fang SY. The expression of human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in the human nasal mucosa[J]. Am J Rhinol, 2004, 18(6): 381-385. DOI:10.1177/194589240401800608 |

| [24] |

Smith ME, Stockfelt M, Tengvall S, et al. Endotoxin exposure increases LL-37 - but not calprotectin - in healthy human airways[J]. J Innate Immun, 2017, 9(5): 475-482. DOI:10.1159/000475525 |

| [25] |

Chung WO, Dommisch H, Yin L, et al. Expression of defensins in gingiva and their role in periodontal health and di-sease[J]. Curr Pharm Des, 2007, 13(30): 3073-3083. DOI:10.2174/138161207782110435 |

| [26] |

Missailidis C, Sørensen N, Ashenafi S, et al. Vitamin D and phenylbutyrate supplementation does not modulate gut derived immune activation in HIV-1[J]. Nutrients, 2019, 11(7): 1675. DOI:10.3390/nu11071675 |

| [27] |

Sørensen OE, Gram L, Johnsen AH, et al. Processing of seminal plasma hCAP-18 to ALL-38 by gastricsin: a novel mecha-nism of generating antimicrobial peptides in vagina[J]. J Biol Chem, 2003, 278(31): 28540-28546. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M301608200 |

| [28] |

Emelianov VU, Bechara FG, Gläser R, et al. Immunohistological pointers to a possible role for excessive cathelicidin (LL-37) expression by apocrine sweat glands in the pathoge-nesis of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa[J]. Br J Dermatol, 2012, 166(5): 1023-1034. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10765.x |

| [29] |

Murakami M, Kaneko T, Nakatsuji T, et al. Vesicular LL-37 contributes to inflammation of the lesional skin of palmoplantar pustulosis[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(10): e110677. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0110677 |

| [30] |

Aidoukovitch A, Dahl S, Fält F, et al. Antimicrobial peptide LL-37 and its pro-form, hCAP18, in desquamated epithelial cells of human whole saliva[J]. Eur J Oral Sci, 2020, 128(1): 1-6. DOI:10.1111/eos.12664 |

| [31] |

Hitchon CA, Meng X, El Gabalawy HS, et al. Human host defence peptide LL37 and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody in early inflammatory arthritis[J]. RMD Open, 2019, 5(1): e000874. DOI:10.1136/rmdopen-2018-000874 |

| [32] |

Schrumpf JA, Ninaber DK, van der Does AM, et al. TGF-β1 impairs vitamin D-induced and constitutive airway epithelial host defense mechanisms[J]. J Innate Immun, 2020, 12(1): 74-89. DOI:10.1159/000497415 |

| [33] |

Agak GW, Kao S, Ouyang K, et al. Phenotype and antimicrobial activity of Th17 cells induced by propionibacterium acnes strains associated with healthy and acne skin[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2018, 138(2): 316-324. DOI:10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.842 |

| [34] |

Takahashi T, Yamasaki K. Psoriasis and antimicrobial peptides[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2020, 21(18): 6791. DOI:10.3390/ijms21186791 |

| [35] |

Scheb-Wetzel M, Rohde M, Bravo A, et al. New insights into the antimicrobial effect of mast cells against Enterococcus faecalis[J]. Infect Immun, 2014, 82(11): 4496-4507. DOI:10.1128/IAI.02114-14 |

| [36] |

Svensson D, Nebel D, Voss U, et al. Vitamin D -induced up-regulation of human keratinocyte cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide expression involves retinoid X receptor α[J]. Cell Tissue Res, 2016, 366(2): 353-362. DOI:10.1007/s00441-016-2449-z |

| [37] |

Esfandiyari R, Halabian R, Behzadi E, et al. Performance evaluation of antimicrobial peptide ll-37 and hepcidin and β-defensin-2 secreted by mesenchymal stem cells[J]. Heliyon, 2019, 5(10): e02652. DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02652 |

| [38] |

Bautista-Hernández LA, Gómez-Olivares JL, Buentello-Volante B, et al. Fibroblasts: the unknown sentinels eliciting immune responses against microorganisms[J]. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp), 2017, 7(3): 151-157. DOI:10.1556/1886.2017.00009 |

| [39] |

Smeianov V, Scott K, Reid G. Activity of cecropin P1 and FA-LL-37 against urogenital microflora[J]. Microbes Infect, 2000, 2(7): 773-777. DOI:10.1016/S1286-4579(00)90359-9 |

| [40] |

Turner J, Cho Y, Dinh NN, et al. Activities of LL-37, a cathelin-associated antimicrobial peptide of human neutrophils[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 1998, 42(9): 2206-2214. DOI:10.1128/AAC.42.9.2206 |

| [41] |

Birteksoz-Tan AS, Zeybek Z, Hacioglu M, et al. In vitro activities of antimicrobial peptides and ceragenins against Legionella pneumophila[J]. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2019, 72(5): 291-297. DOI:10.1038/s41429-019-0148-1 |

| [42] |

Ciandrini E, Morroni G, Arzeni D, et al. Antimicrobial activity of different antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) against clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)[J]. Curr Top Med Chem, 2018, 18(24): 2116-2126. |

| [43] |

Geitani R, Ayoub Moubareck C, Touqui L, et al. Cationic antimicrobial peptides: alternatives and/or adjuvants to antibio-tics active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa[J]. BMC Microbiol, 2019, 19(1): 54. DOI:10.1186/s12866-019-1416-8 |

| [44] |

Huang YY, Alumasa JN, Callaghan LT, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of trans-translation synergistically interacts with cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides to impair survival of Staphy-lococcus aureus[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2019, 63(4): e02362-18. |

| [45] |

Lin L, Nonejuie P, Munguia J, et al. Azithromycin synergizes with cationic antimicrobial peptides to exert bactericidal and therapeutic activity against highly multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial pathogens[J]. EBioMedicine, 2015, 2(7): 690-698. DOI:10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.05.021 |

| [46] |

Luo Y, McLean DT, Linden GJ, et al. The naturally occurring host defense peptide, LL-37, and its truncated mimetics KE-18 and KR-12 have selected biocidal and antibiofilm activities against Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli in vitro[J]. Front Microbiol, 2017, 8: 544. |

| [47] |

Koppen BC, Mulder PPG, de Boer L, et al. Synergistic microbicidal effect of cationic antimicrobial peptides and teicoplanin against planktonic and biofilm-encased Staphylococcus aureus[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2019, 53(2): 143-151. DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.10.002 |

| [48] |

Tian XL, Salim H, Dong G, et al. The BceABRS four-component system that is essential for cell envelope stress response is involved in sensing and response to host defence peptides and is required for the biofilm formation and fitness of Streptococcus mutans[J]. J Med Microbiol, 2018, 67(6): 874-883. DOI:10.1099/jmm.0.000733 |

| [49] |

Xie F, Zan YN, Zhang YL, et al. The cysteine protease ApdS from Streptococcus suis promotes evasion of innate immune defenses by cleaving the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin LL-37[J]. J Biol Chem, 2019, 294(47): 17962-17977. DOI:10.1074/jbc.RA119.009441 |

| [50] |

Urashima A, Sanou A, Yen H, et al. Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli produces outer membrane vesicles as an active defence system against antimicrobial peptide LL-37[J]. Cell Microbiol, 2017, 19(11): e12758. DOI:10.1111/cmi.12758 |

| [51] |

Munguia J, Larock DL, Tsunemoto H, et al. The Mla pathway is critical for Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistance to outer membrane permeabilization and host innate immune clearance[J]. J Mol Med (Berl), 2017, 95(10): 1127-1136. DOI:10.1007/s00109-017-1579-4 |

| [52] |

Malhotra S, Limoli DH, English AE, et al. Mixed communities of mucoid and nonmucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa exhibit enhanced resistance to host antimicrobials[J]. mBio, 2018, 9(2): e00275-18. |

| [53] |

Ordonez SR, Amarullah IH, Wubbolts RW, et al. Fungicidal mechanisms of cathelicidins LL-37 and CATH-2 revealed by live-cell imaging[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2014, 58(4): 2240-2248. DOI:10.1128/AAC.01670-13 |

| [54] |

López-García B, Lee PH, Yamasaki K, et al. Anti-fungal activity of cathelicidins and their potential role in Candida albicans skin infection[J]. J Invest Dermatol, 2005, 125(1): 108-115. DOI:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23713.x |

| [55] |

Jiang LL, Fang MF, Tao RC, et al. Recombinant human interleukin 17A enhances the anti-Candida effect of human oral mucosal epithelial cells by inhibiting Candida albicans growth and inducing antimicrobial peptides secretion[J]. J Oral Pathol Med, 2020, 49(4): 320-327. DOI:10.1111/jop.12889 |

| [56] |

Fan D, Coughlin LA, Neubauer MM, et al. Activation of HIF-1α and LL-37 by commensal bacteria inhibits Candida albicans colonization[J]. Nat Med, 2015, 21(7): 808-814. DOI:10.1038/nm.3871 |

| [57] |

Tsai PW, Yang CY, Chang HT, et al. Characterizing the role of cell-wall β-1, 3-exoglucanase Xog1p in Candida albicans adhesion by the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(6): e21394. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0021394 |

| [58] |

Tsai PW, Yang CY, Chang HT, et al. Human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 inhibits adhesion of Candida albicans by intera-cting with yeast cell-wall carbohydrates[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(3): e17755. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0017755 |

| [59] |

Tsai PW, Cheng YL, Hsieh WP, et al. Responses of Candida albicans to the human antimicrobial peptide LL-37[J]. J Microbiol, 2014, 52(7): 581-589. DOI:10.1007/s12275-014-3630-2 |

| [60] |

Szafranski-Schneider E, Swidergall M, Cottier F, et al. Msb2 shedding protects Candida albicans against antimicrobial peptides[J]. PLoS Pathog, 2012, 8(2): e1002501. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002501 |

| [61] |

Swidergall M, Ernst AM, Ernst JF. Candida albicans mucin Msb2 is a broad-range protectant against antimicrobial peptides[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2013, 57(8): 3917-3922. DOI:10.1128/AAC.00862-13 |

| [62] |

Arampatzioglou A, Papazoglou D, Konstantinidis T, et al. Clarithromycin enhances the antibacterial activity and wound healing capacity in type 2 diabetes mellitus by increasing LL-37 load on neutrophil extracellular traps[J]. Front Immunol, 2018, 9: 2064. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02064 |

| [63] |

Schröder JM. The role of keratinocytes in defense against infection[J]. Curr Opin Infect Dis, 2010, 23(2): 106-110. DOI:10.1097/QCO.0b013e328335b004 |

| [64] |

Chieosilapatham P, Ikeda S, Ogawa H, et al. Tissue-specific regulation of innate immune responses by human cathelicidin LL-37[J]. Curr Pharm Des, 2018, 24(10): 1079-1091. DOI:10.2174/1381612824666180327113418 |

| [65] |

Choi KY, Napper S, Mookherjee N. Human cathelicidin LL-37 and its derivative IG-19 regulate interleukin-32-induced inflammation[J]. Immunology, 2014, 143(1): 68-80. DOI:10.1111/imm.12291 |

| [66] |

Beaumont PE, McHugh B, Gwyer Findlay E, et al. Cathelicidin host defence peptide augments clearance of pulmonary Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection by its influence on neutrophil function in vivo[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(6): e99029. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0099029 |

| [67] |

van der Does AM, Beekhuizen H, Ravensbergen B, et al. LL-37 directs macrophage differentiation toward macrophages with a proinflammatory signature[J]. J Immunol, 2010, 185(3): 1442-1449. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1000376 |

| [68] |

Davidson DJ, Currie AJ, Reid GS, et al. The cationic antimicrobial peptide LL-37 modulates dendritic cell differentiation and dendritic cell-induced T cell polarization[J]. J Immunol, 2004, 172(2): 1146-1156. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1146 |

| [69] |

Alós JI. Antibiotic resistance: A global crisis[J]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin, 2015, 33(10): 692-699. DOI:10.1016/j.eimc.2014.10.004 |

| [70] |

Taylor A, Littmann J, Holzscheiter A, et al. Sustainable development levers are key in global response to antimicrobial resistance[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10214): 2050-2051. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32555-3 |

| [71] |

Tzitzilis A, Boura-Theodorou A, Michail V, et al. Cationic amphipathic peptide analogs of cathelicidin LL-37 as a probe in the development of antimicrobial/anticancer agents[J]. J Pept Sci, 2020, 26(7): e3254. |