2. 南方医科大学南方医院超声医学科, 广东 广州 510515;

3. 深圳市龙华区人民医院呼吸内科, 广东 深圳 518109;

4. 广东省中医院芳村分院重症医学科, 广东 广州 510000;

5. 南方医科大学南方医院惠侨医疗中心呼吸病区全科医学规培基地, 广东 广州 510515

2. Department of Ultrasound, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China;

3. Department of Respiratory Medicine, The People's Hospital of Longhua District of Shenzhen, Shenzhen 518109, China;

4. Intensive Care Unit, Fangcun Branch of Guangdong Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou 510000, China;

5. General Medicine Base, Huiqiao Medical Center, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China

假丝酵母菌是引起医院获得性血流感染的第4位病原菌[1-2],在最近一项来自美国的多区域研究中,假丝酵母菌菌血症是最常见的医院获得性真菌血流感染[3]。假丝酵母菌菌血症的病死率高达50%[4-5],年医疗保健费用高达20亿美元[6-7],受到临床医生的广泛关注。本研究回顾性分析南方医科大学南方医院240例医院获得性假丝酵母菌菌血症患者的临床资料,旨在分析包括临床特征、菌种分布在内的假丝酵母菌菌血症流行病学特征,影响预后的因素,以及其分离株对抗真菌药物的敏感性,为临床诊断和合理用药提供理论依据。

1 对象与方法 1.1 研究对象选取2008年1月1日—2018年12月31日在南方医院住院的患者。纳入标准:年龄≥18岁,入院48 h后微生物学确认为假丝酵母菌菌血症,电子病历资料没有缺失与研究相关的数据。对于研究期间多次发生假丝酵母菌菌血症感染的患者,只分析首次血流感染情况。本研究为回顾性、单中心研究,已经由南方医科大学南方医院伦理委员会审核批准通过(项目批准文号:NFEC-2017-036),并豁免知情同意权。

1.2 相关定义近期使用过抗菌药物/抗真菌药物:在假丝酵母菌菌血症发生前30 d内使用过抗菌药物/抗真菌药物。4周内行腹部侵入性操作:在假丝酵母菌菌血症发生前4周内对胃肠道进行的任何类型的侵入性操作(如食管、胃、十二指肠镜检查和结肠镜活检)。脓毒性休克:在脓毒症的基础上,充分容量复苏后仍需血管活性药物维持平均动脉压≥65 mmHg及血乳酸浓度>2 mmol/L[8]。器官衰竭按参考文献[9-15]中的定义。

1.3 方法 1.3.1 研究方法根据医院获得性假丝酵母菌菌血症患者的最终治疗结局,分为生存组和死亡组,对不同分组患者的临床资料进行研究,确定假丝酵母菌菌血症患者死亡的独立危险因素,并分析假丝酵母菌菌株分布及对抗真菌药物的敏感情况。

1.3.2 真菌培养、鉴定及药敏检测方法当患者出现发热、血压低、白细胞增多或减少等血流感染相关症状时,采集患者外周血,并及时将标本送至临床微生物学实验室,检验科医务人员应用Autobio真菌快速培养鉴定药敏试剂盒(中国郑州)及江门凯林P0721假丝酵母菌属真菌显色培养基(培养法,中国江门)对血样本进行真菌培养,根据培养基指示剂颜色变化以及质谱分析结果,判断真菌感染种类及对氟康唑、氟胞嘧啶、伊曲康唑、两性霉素B的敏感性。

1.4 统计学方法应用SPSS 20.0软件进行统计分析。正态分布的计量资料以(x±s)表示,两组间比较采用独立样本t检验,多组间比较,若方差齐采用one-way ANOVO,方差不齐采用Kruskal-Wallis检验;偏态分布的计量资料以M(QR)表示,两组间比较采用Mann-whitney U检验;计数资料以相对数表示,两组间比较采用χ2检验。采用单因素分析和多因素logistic回归分析假丝酵母菌菌血症患者死亡的独立危险因素。以P≤0.05为差异有统计学意义。应用GraphPad Prism 5绘图。

2 结果 2.1 临床特征2008年1月1日—2018年12月31日共收治医院获得性假丝酵母菌菌血症患者240例,其中生存组172例,死亡组68例。平均年龄为(50.4±16.6)岁,平均住院时长为35(21~57)d,其中,男性较为多见(64.6%)。92.9%(223例)的患者至少有一种基础疾病,两种及以上基础疾病患者占60.4%(145例);癌症是最常见的基础疾病(45.0%);器官衰竭的发生例数为90例(37.5%);脓毒性休克的发生例数为37例(15.4%)。

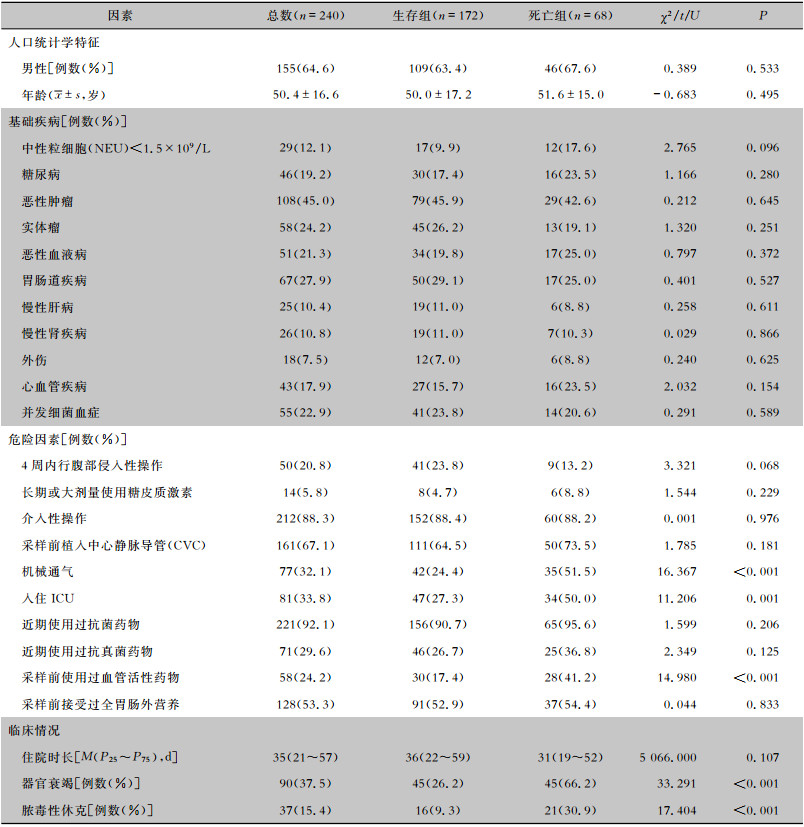

2.2 医院获得性假丝酵母菌菌血症患者死亡的危险因素分析 2.2.1 单因素分析两组患者的临床特征及危险因素的单因素分析见表 1。结果显示,医院获得性假丝酵母菌菌血症患者死亡的危险因素为:机械通气、入住重症监护病房(ICU)、采样前使用过血管活性药物、器官衰竭、脓毒性休克,与生存组患者比较,差异均有统计学意义(均P<0.05)。

| 表 1 死亡组与存活组患者临床特征及死亡的单因素分析 Table 1 Univariate analysis on clinical characteristics and death of patients in death group and survival group |

|

将单因素分析结果中有意义的因素纳入回归方程进行多因素分析,结果显示,器官衰竭[OR(95% CI):5.872(2.904~11.874),P < 0.001]、脓毒性休克[OR(95% CI):3.313(1.435~7.649),P=0.005]是假丝酵母菌菌血症患者死亡的独立危险因素。

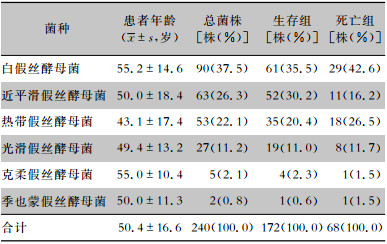

2.3 假丝酵母菌菌种分布及变化趋势 2.3.1 医院获得性假丝酵母菌血流感染菌株分布240例医院获得性假丝酵母菌血流感染病例共分离出白假丝酵母菌90株(37.5%),近平滑假丝酵母菌63株(26.3%),热带假丝酵母菌53株(22.1%),光滑假丝酵母菌27株(11.2%),克柔假丝酵母菌5株(2.1%),季也蒙假丝酵母菌2株(0.8%)。生存组与死亡组患者分离假丝酵母菌菌种构成比较,差异无统计学意义(χ2=5.821,P=0.324)。白假丝酵母菌菌血症患者平均年龄(55.2±14.6)高于近平滑假丝酵母菌(50.0±18.4)和热带假丝酵母菌菌血症患者(43.1±17.4),近平滑假丝酵母菌菌血症患者平均年龄高于热带假丝酵母菌,差异均有统计学意义(均P<0.05)。见表 2、图 1。

| 表 2 240株假丝酵母菌来源患者年龄及菌种分布 Table 2 Distribution of 240 strains of Candida species and patients' age |

|

|

| *:P<0.05,**:P<0.001 图 1 240株假丝酵母菌来源患者年龄分布图 Figure 1 Age distribution of patients who isolated 240 strains of Candida |

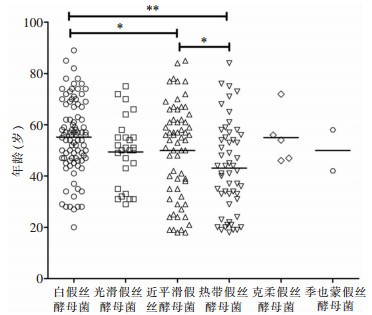

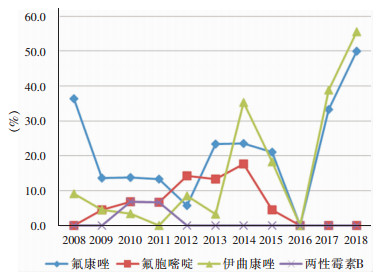

2008—2014年,该院白假丝酵母菌检出比例呈逐渐上升趋势,近两年白假丝酵母菌检出比例有所回落,其他假丝酵母菌比例有所上升。见图 2。

|

| 图 2 2008—2018年该院分离假丝酵母菌菌种分布 Figure 2 Distribution of Candida species in this hospital from 2008 to 2018 |

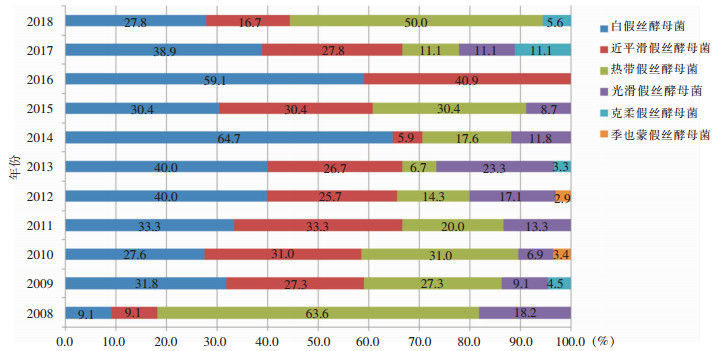

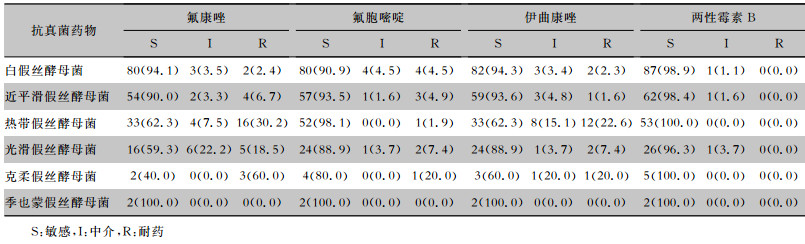

血培养分离的假丝酵母菌对氟康唑敏感率最低(80.6%),对其他抗真菌药物氟胞嘧啶、伊曲康唑、两性霉素B的敏感率分别为92.8%、85.7%、98.7%。对氟康唑敏感率由高到低的假丝酵母菌种类依次为:季也蒙假丝酵母菌(100.0%)、白假丝酵母菌(94.1%)、近平滑假丝酵母菌(90.0%)、热带假丝酵母菌(62.3%)、光滑假丝酵母菌(59.3%)、克柔假丝酵母菌(40.0%)。此外,热带假丝酵母菌和克柔假丝酵母菌对伊曲康唑的敏感率也偏低,分别为62.3%和60.0%。季也蒙假丝酵母菌对四种抗真菌药物均敏感。见表 3。近两年分离出的唑类不敏感分离株明显增多,尤其2018年超过50%的分离株对唑类不敏感,见图 3。

| 表 3 医院获得性血流感染假丝酵母菌对抗真菌药物的敏感性[株(%)] Table 3 Antifungal susceptibility of Candida causing hospital-acquired bloodstream infection (No. of isolates [%]) |

|

|

| 图 3 2008—2018年假丝酵母菌属菌株对抗真菌药物耐药率变化趋势图 Figure 3 Changing trend in resistance rates of Candida spp. to antifungal agents from 2008 to 2018 |

医院获得性假丝酵母菌菌血症是患者入院48 h后至少一次假丝酵母菌血培养阳性且伴随有假丝酵母菌菌血症症状或体征的疾病[16],常发生于免疫力低下的人群[17]。近年来,由于临床上广谱抗菌药物、糖皮质激素、免疫抑制剂、化学治疗药物的使用越来越多,以及中心静脉置管、血液透析等多种侵袭性诊疗操作的广泛开展,医院获得性假丝酵母菌菌血症的发病率不断上升[18]。

本研究结果显示,白假丝酵母菌仍然是引起医院获得性假丝酵母菌菌血症最常见的病原菌,与国内外的流行病学调查研究结果[19-20]基本一致,该院分离的白假丝酵母菌占37.5%,低于中国侵袭性真菌耐药监测网(CHIF-NET)全国侵袭性假丝酵母菌五年的监测结果(白假丝酵母菌占44.9%)[20]。近年来,以唑类为主的抗真菌药物的临床应用不断增加,导致非白假丝酵母菌在假丝酵母菌菌血症中的发病率逐渐升高[21],有些国家或地区甚至已超过50.0%[22],美国一项关于急性白血病患者的研究显示,非白假丝酵母菌感染导致的假丝酵母菌菌血症高达99%[5]。本研究中该院近10年的数据显示,非白假丝酵母菌感染占62.5%,其中,血培养分离的最常见非白假丝酵母菌为近平滑假丝酵母菌,与Barchiesi等[23]研究结果相似。与白假丝酵母菌和近平滑假丝酵母菌菌血症患者相比,热带假丝酵母菌菌血症患者较为年轻,平均年龄为(43.1±17.4)岁,与Fernández-Ruiz等[24]报道的热带假丝酵母菌菌血症与高龄(63.0±22.8)显著相关的结果相反,有待进一步研究。

药敏试验是目前指导临床用药和监测耐药的重要手段。氟康唑常作为临床上假丝酵母菌感染的首选经验用药。本研究体外药敏试验结果显示,假丝酵母菌对氟康唑的敏感率最低,且敏感率逐年下降,除克柔假丝酵母菌对氟康唑天然耐药外,白假丝酵母菌、近平滑假丝酵母菌、热带假丝酵母菌和光滑假丝酵母菌对氟康唑的敏感率分别为94.1%、90.0%、62.3%和59.3%,与Pfaller等[25]报道的结果相近。以上现象可能与临床上对氟康唑的过度使用,从而促进耐药菌株的产生有关。两性霉素B是抗真菌治疗的主要药物,尽管近年来出现了对两性霉素B耐药的假丝酵母菌[26],但该院体外药敏结果未发现对两性霉素B耐药的假丝酵母菌菌株。但由于两性霉素B的肝肾毒性,故常不作为治疗假丝酵母菌菌血症的首选药物。基于目前假丝酵母菌对唑类药物的敏感性呈逐年下降的趋势,美国传染病学会指南推荐棘白菌素作为治疗假丝酵母菌菌血症的一线治疗用药[27]。

本研究中医院获得性假丝酵母菌菌血症患者的病死率为28.3%,与国内外报道[28-29]相近。单因素分析结果显示:入住ICU、机械通气、脓毒性休克、采样前使用血管活性药物和器官衰竭与假丝酵母菌菌血症患者死亡相关,与相关研究[30-32]结果一致;进一步logistic回归多因素分析显示,器官衰竭及脓毒性休克是患者死亡的独立危险因素。脓毒性休克与假丝酵母菌菌血症患者死亡直接相关,可能与未及时抗真菌治疗有关[28];器官衰竭可导致严重的疾病状态。因此,上述因素均与死亡密切相关。

本研究的局限性:(1)本研究是一项回顾性、单中心研究,样本量小,可能结论不具有普遍性。(2)由于该院检验科仅对氟康唑、氟胞嘧啶、伊曲康唑和两性霉素B这四种药物做体外抗真菌药物敏感性检测,故未检测假丝酵母菌对棘白菌素类和泊沙康唑等新唑类药物的敏感性,因此,本研究可能缺失一些对棘白菌素或新唑类药物耐药的药敏资料。(3)由于时间有限,本研究未探讨假丝酵母菌菌血症的可归因死亡率、持续或再发的假丝酵母菌菌血症,未研究导管相关性假丝酵母菌菌血症对患者临床结局的效应。

综上所述,假丝酵母菌菌血症患者具有基础疾病多、病情重、病死率高等特点,临床医生应重点关注具有高危因素的医院获得性假丝酵母菌菌血症患者,监测假丝酵母菌种类的分布及变化趋势,评估抗真菌药物的敏感性,合理选用抗真菌药物,以提高该疾病的诊疗水平。

| [1] |

Ani C, Farshidpanah S, Bellinghausen SA, et al. Variations in organism-specific severe sepsis mortality in the United States: 1999-2008[J]. Crit Care Med, 2015, 43(1): 65-77. |

| [2] |

Kullberg BJ, Arendrup MC. Invasive candidiasis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(15): 1445-1456. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra1315399 |

| [3] |

Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections[J]. N Engl J Med, 2014, 370(13): 1198-1208. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1306801 |

| [4] |

Farmakiotis D, Kyvernitakis A, Tarrand JJ, et al. Early initiation of appropriate treatment is associated with increased survival in cancer patients with Candida glabrata fungaemia: a potential benefit from infectious disease consultation[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2015, 21(1): 79-86. DOI:10.1016/j.cmi.2014.07.006 |

| [5] |

Wang E, Farmakiotis D, Yang D, et al. The ever-evolving landscape of candidaemia in patients with acute leukaemia: non-susceptibility to caspofungin and multidrug resistance are associated with increased mortality[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2015, 70(8): 2362-2368. DOI:10.1093/jac/dkv087 |

| [6] |

Zaoutis TE, Argon J, Chu J, et al. The epidemiology and attributable outcomes of candidemia in adults and children hospitalized in the United States: a propensity analysis[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2005, 41(9): 1232-1239. DOI:10.1086/496922 |

| [7] |

Pfaller M, Neofytos D, Diekema D, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 3 648 patients: data from the prospective antifungal therapy (PATH Alliance®) registry, 2004-2008[J]. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 2012, 74(4): 323-331. DOI:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.10.003 |

| [8] |

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3)[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8): 801-810. DOI:10.1001/jama.2016.0287 |

| [9] |

中华医学会心血管病学分会心力衰竭学组, 中国医师协会心力衰竭专业委员会, 中华心血管病杂志编辑委员会. 中国心力衰竭诊断和治疗指南2018[J]. 中华心血管病杂志, 2018, 46(10): 760-789. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-3758.2018.10.004 |

| [10] |

Makris K, Spanou L. Acute kidney injury: definition, pathophysiology and clinical phenotypes[J]. Clin Biochem Rev, 2016, 37(2): 85-98. |

| [11] |

孙伟.慢性肾衰竭中西医结合诊疗指南[C].2016年中国中西医结合学会肾脏疾病专业委员会学术年会, 上海, 2016.

|

| [12] |

Singh TD, O'Horo JC, Gajic O, et al. Risk factors and outcomes of critically ill patients with acute brain failure: a novel end point[J]. J Crit Care, 2018, 43: 42-47. DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.08.028 |

| [13] |

中华医学会感染病学分会肝衰竭与人工肝学组, 中华医学会肝病学分会重型肝病与人工肝学组. 肝衰竭诊治指南(2018年版)[J]. 西南医科大学学报, 2019, 42(2): 99-106. |

| [14] |

英国血液学标准化委员会. 弥散性血管内凝血诊断指南[J]. 内科理论与实践, 2010, 5(4): 358-360. |

| [15] |

Shebl E, Burns B. Respiratory failure[M]. StatPearls Publishing, 2019.

|

| [16] |

Gudlaugsson O, Gillespie S, Lee K, et al. Attributable morta-lity of nosocomial candidemia, revisited[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2003, 37(9): 1172-1177. DOI:10.1086/378745 |

| [17] |

Ghrenassia E, Mokart D, Mayaux J, et al. Candidemia in critically ill immunocompromised patients: report of a retrospective multicenter cohort study[J]. Ann Intensive Care, 2019, 9(1): 62. DOI:10.1186/s13613-019-0539-2 |

| [18] |

Kashiha A, Setayesh N, Panahi Y, et al. Prevalence of candidemia and associated candida subtypes following severe sepsis in non-neutropenic critically ill patients[J]. Acta Biomed, 2018, 89(2): 193-202. |

| [19] |

Pappas PG, Lionakis MS, Arendrup MC, et al. Invasive candidiasis[J]. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2018, 4: 18026. DOI:10.1038/nrdp.2018.26 |

| [20] |

Xiao M, Sun ZY, Kang M, et al. Five-year national surveillance of invasive candidiasis: species distribution and azole susceptibility from the China Hospital Invasive Fungal Surveillance Net (CHIF-NET) Study[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2018, 56(7): pii: e00577-18. |

| [21] |

Whaley SG, Berkow EL, Rybak JM, et al. Azole antifungal resistance in Candida albicans and emerging non-albicans Candida species[J]. Front Microbiol, 2016, 7: 2173. |

| [22] |

Salehi M, Ghomi Z, Mirshahi R, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in a referral center in Tehran[J]. Caspian J Intern Med, 2019, 10(1): 73-79. |

| [23] |

Barchiesi F, Orsetti E, Gesuita R, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and outcome of candidemia in a tertiary referral center in Italy from 2010 to 2014[J]. Infection, 2016, 44(2): 205-213. DOI:10.1007/s15010-015-0845-z |

| [24] |

Fernández-Ruiz M, Puig-Asensio M, Guinea J, et al. Candida tropicalis bloodstream infection: Incidence, risk factors and outcome in a population-based surveillance[J]. J Infect, 2015, 71(3): 385-394. DOI:10.1016/j.jinf.2015.05.009 |

| [25] |

Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Gibbs DL, et al. Results from the Artemis Disk Global Antifungal Surveillance Study, 1997 to 2007: a 10.5-year analysis of susceptibilities of Candida species to fluconazole and voriconazole as determined by CLSI standardized disk diffusion[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2010, 48(4): 1366-1377. DOI:10.1128/JCM.02117-09 |

| [26] |

Dagi HT, Findik D, Senkeles C, et al. Identification and antifungal susceptibility of Candida species isolated from bloodstream infections in Konya, Turkey[J]. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob, 2016, 15(1): 36. DOI:10.1186/s12941-016-0153-1 |

| [27] |

Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2016, 62(4): e1-50. DOI:10.1093/cid/civ1044 |

| [28] |

Jia X, Li C, Cao J, et al. Clinical characteristics and predictors of mortality in patients with candidemia: a six-year retrospective study[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2018, 37(9): 1717-1724. DOI:10.1007/s10096-018-3304-9 |

| [29] |

Kato H, Yoshimura Y, Suido Y, et al. Mortality and risk factor analysis for Candida blood stream infection: a multicenter study[J]. J Infect Chemother, 2019, 25(5): 341-345. DOI:10.1016/j.jiac.2019.01.002 |

| [30] |

Wang TY, Hung CY, Shie SS, et al. The clinical outcomes and predictive factors for in-hospital mortality in non-neutropenic patients with candidemia[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2016, 95(23): e3834. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000003834 |

| [31] |

Hesstvedt L, Gaustad P, Müller F, et al. The impact of age on risk assessment, therapeutic practice and outcome in candidemia[J]. Infect Dis (Lond), 2019, 51(6): 425-434. DOI:10.1080/23744235.2019.1595709 |

| [32] |

Sbrana F, Sozio E, Bassetti M, et al. Independent risk factors for mortality in critically ill patients with candidemia on Italian Internal Medicine Wards[J]. Intern Emerg Med, 2018, 13(2): 199-204. DOI:10.1007/s11739-017-1783-9 |